Jemele Hill Shares Her Story of Trauma and Perseverance

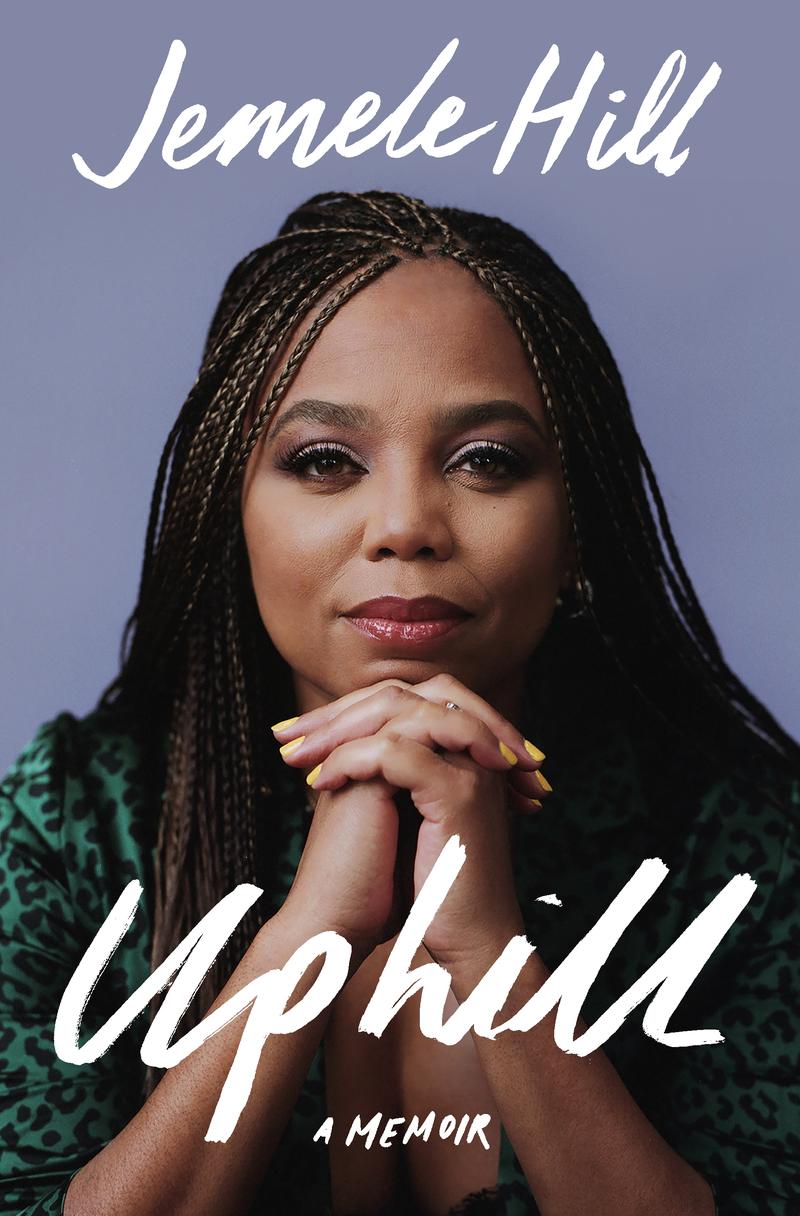

( Courtesy of Henry Holt & Company )

[music]

Melissa Harris-Perry: It's The Takeaway. I'm Melissa Harris-Perry.

Back in 2017, Jemele Hill and Michael Smith became hosts of ESPN's 6:00 PM hour of SportsCenter. The duo were already a bit of an ESPN juggernaut, having hosted the personality-driven sports show, His & Hers, since 2012, first as a podcast, then as a daytime offering.

Jemele Hill remains one of the most recognizable Black women's sports reporters in the country, but it was a journey that began for her as a young print reporter in North Carolina, and later Florida.

Jemele Hill: "Eventually, I grew out of being a terrible columnist by putting way less pressure on myself."

Melissa Harris-Perry: This is Jemele Hill reading from her new book, Uphill: A Memoir.

Jemele Hill: "I was still cognizant of the fact that as the only Black female sports columnist at a daily newspaper in the country, I couldn't afford to fail, but I was also driven by wanting to be an example for other Black women in the business and for those considering a sports writing career. I couldn't give up just because I had some growing pains. Other Black women and girls were watching. Eventually, I started to find my voice."

Melissa Harris-Perry: Indeed, she seems to have found her voice in the new memoir. For those who followed her career, the book is both familiar and surprising.

Jemele Hill: A lot of people will be probably a bit surprised when they read the memoir because you know how it is when you're a public figure and have a high profile, that people only know you through the work prism, through seeing me on ESPN for many years, or maybe through my post-ESPN life with some of the other projects that I've done. This was my opportunity to tell a more complete and full story about who I am and how I came to be so people understand, maybe to some degree, why I say some of the things that I say and have some of the positions that I have.

Melissa Harris-Perry: I sat down to talk with Jemele Hill.

Jemele Hill: My grandmother was a fiercely independent person, who very much was a critical thinker, and that's something she definitely instilled in me. We just had such a great close relationship. I think to some degree, the way that she treated me, how nurturing she was, was the way that she probably wished she could have been more with my mother. Her and my mother, they had a very complicated, loving, but sometimes difficult relationship as mothers and daughters tend to do.

There was just this rift that never healed between them because my mother was sexually abused by my grandmother's brother when she was younger from ages 4 to 11. As a result of that and the fact that my grandmother did not believe her, it really broke something in their relationship that even upon my grandmother's death in 2010, I don't think ever recovered. Certainly, my mother loved her unconditionally, and even during times where their relationship hit a rocky point, my mother was always there from her.

It was only maybe once or twice in my mother's life where she lived more than 15 minutes away from my grandmother, [chuckles] because she really felt quite close to her. Even at times when they went back and forth, if you will. It was a dynamic that, as a child, was sometimes difficult for me to understand. Sometimes it put me in the middle of it, which wasn't a great place for me to be. For all of my grandmother's flaws, my mother loved her through them, and so it taught me something about the dynamic.

I think because of their dynamic, my mother wanted to make sure that that didn't happen with us. These are relatable things that play out in a lot of families. I wanted to make sure that I was transparent and shared mine because I know that sometimes when there are these complicated relationships in our family, that there tends to be a level of shame that are attached to them.

I wanted to make sure that I was as transparent as possible to hopefully remove the shame that sometimes feel about, whether it'd be sexual abuse within the family, or sometimes these complicated dynamics between mothers and daughters, I wanted to just give room to breathe life into, hopefully, some new conversations.

Melissa Harris-Perry: What is the intergenerational story of sexual assault that you're giving us here?

Jemele Hill: There was so much unhealed and very obvious brokenness in my mother that I did not understand at that age. One of her vows she made to herself was that she would make sure that never happened to me. That if there was ever anything that in any way in which I felt uncomfortable, that I would always be able to come to her and tell her.

She felt like the safety and protection that she needed she didn't get, especially from my grandmother, because when she revealed her own abuse my grandmother didn't believe her and there were other family members that also did not believe my mother. My mother wanted to make sure I never faced something like that.

As I write about in the memoir, I disclose the incident in which somebody tried to rape me, the first person I told was my mother, and she acted as you would want any mother to act. She tried to physically harm the person who did it. She drove me to the police station because she asked me if I wanted to file a police report. I told her that I did.

Even though they never did anything, the police, that is, in my situation either, I also thought that this was just an important step for me. There's a trauma that was broken because of the way that my mother had always talked to me about sexual abuse. She talked to me about what happened to her, that, in many ways, that was her way of trying to break the cycle.

Melissa Harris-Perry: It seems to me that part of what you're writing about here is it also meant some anger, anger that you opened the book with in some ways. Talk to me about what anger looks like for Black girls and women who are sometimes just trying to heal.

Jemele Hill: As you just alluded to, I started the book talking about how one of the reasons I started going to therapy is because my mother accused me of being angry. I thought she was wrong and I was angry that she thought I was angry. [laughs] I was like, "I'm not angry." It was true. I don't really think anger was my issue. I do think that what happens, and again, something very common in mother-daughter relationships is that, when you try to establish certain boundaries, mothers don't always like boundaries. [laughs]

Melissa Harris-Perry: No. We're not for those. I don't know if you've heard. [laughs]

Jemele Hill: No, you're not. You're not really for those. She would sometimes take my pushback as being angry and maybe related to some unresolved feelings that I had toward her when I was like, "No, they have nothing to do with that. They have everything to do within the present." [laughs] I do think, for me, the only-- I think this is part of the reason why I'm so passionate about things that I'm involved with, the things that I do, is one of the things that happens when you grow up as the child of an addict is you lose your sense of agency.

If there was anything that I may have been not necessarily angry about but wanted to make sure that I always had later on in my life is a sense of agency because when you're growing up with somebody who has been an addict, you're navigating around their addiction all the time. It is the living, breathing elephant in the room all the time. Whether it is adapting to certain moods, whether it's trying to figure out what dynamic you're about to see or come home to, these were all a regular part of my existence.

The loss of agency, not feeling as if I was in control or had any say in anything that was happening, left me feeling helpless. It was a feeling I never wanted to repeat. Obviously, as I'm growing into adulthood, one of the reasons why I think my career became my safe haven that I poured so much of my time, and energy, and methodical planning into is because it was, as I write, "the one thing I could count on not to let me down."

Even though that sounds crazy to say because we know that in your professional life you're going to be let down by it, that's just inevitable, but I felt more in control of that and I clung to that. Going to therapy didn't teach me I was angry, it did teach me I was a control freak.

[laughter]

Jemele Hill: There's that revelation, for sure.

Melissa Harris-Perry: All right, let's take a quick break. I'll be back with more of my conversation with Jemele Hill right after this break.

[music]

Melissa Harris-Perry: It's MHP on The Takeaway, and we're back and talking with Jemele Hill about her memoir, Uphill. I asked her about being a Black woman sports reporter.

Jemele Hill: One thing I think that maybe people don't necessarily know, or think about in these terms is that sports media is overwhelmingly white. As you know, I wrote about in the book, when I became a columnist at the Orlando Sentinel, I was the only Black female sports columnist at a daily newspaper in North America, not just America.

Because you have that dynamic of Black players, white ownership, mostly white sports media covering them, then there's some inherent power dynamics in that. There's some inherent uncomfortable racial optics in there. Part of covering sports is you should understand what that dynamic is and what it means and how that translates to the narratives that we often hear and read about athletes, Black athletes in particular.

I think even within the form of sports, there's this fallacy that pervades over it, which is why people tend to be so emotional about sports, where people like to believe that sports is completely meritocracy based. Mostly that is true. LeBron James is great. You can watch him and see that. That is no news flash to anyone. There's these other more political dynamics that are taking place in sports that despite what people like to think, the real world interferes.

People like to act like the things that are happening in say, our country like you just mentioned, extremism, white supremacy, and all that are happening in one alternate universe and sports remains totally untouched. No, no, no, no, no, no, this is not the case. Sports, if anything allows those dynamics of real-world problems become even more loud and bold in sports.

Melissa Harris-Perry: In September 2017, Jemele tweeted out a series of sentiments about President Donald Trump referring to him as "a white supremacist," who, "has largely surrounded himself with other white supremacists." In response, ESPN Suspended Hill. She later left the network altogether.

Jemele Hill: I don't think I've been sent home ever [chuckles] from anything, from school, from nothing. It was humiliating. Maybe humiliation wasn't the emotion I should have felt, but that was what I felt in the moment. John Skipper and I are friends, we're still friends. That was obviously a very rough moment in our relationship.

Even with that, I understood his perspective only in the sense of he's this president of a major sports network, the major sports network in fact, and there had been a mounting amount of criticism that was directed at ESPN. They were accused of being too liberal, too political. It was interesting how those labels kept getting thrown at ESPN. It coincided at a time where there was a lot of very diverse talent having becoming more faces of the network because you had me, you had Michael Smith, Stephen A. Smith, Sarah Spain, Kate Fagan, Omari Jones, a ton of names.

This was an entirely new crop of faces that people weren't used to seeing in this position at ESPN. Inherently, as you know that whenever they start seeing more Black and Brown faces, more women, more members of the LGBTQ community, then suddenly it's too political, it's too liberal because they're just basically saying our presence is too liberal, and too political, [laughs] which is not so coded racism.

ESPN was in some real political crosshairs and they were not used to being there. They're used to being the cool kids at the lunch table all the time. This was a very challenging time for the network. Then you add in the grenade of me [chuckles] saying what I said about the president and Skipper really didn't know what to do because on one end, the one thing he never said is I was wrong. [laughs]

That's number one. I mean, I'm not leaping to a conclusion. I mean, he's never really shared his political beliefs, but he didn't say, "You crazy." [laughs] That's for sure. On one hand, you have ESPN at a very difficult and pivotal moment. For as many people that were vehement in their criticism of me and saying that I should be fired and all this other stuff.

There was also a lot of people who agreed. That put him in a very interesting position. Not just a lot of people just as in the public, we're talking about some very prominent Black athletes who showed their support of me, Colin Kaepernick, Kevin Durant, Dwayne Wade, LeBron James. These are athletes that the network wants to be in business with [chuckles] too.

If they have my back, then it puts him in a position of, "Do I want to be the network president that comes down hard on a Black woman who is basically speaking an obvious truth about the leader of our country?" It was certainly a telling moment, but as I say in the book, ultimately the conclusion of that was I got sent home for just a couple of hours and then I came back and did the show. [laughs]

Melissa Harris-Perry: How are you feeling about the future these days?

Jemele Hill: Feeling really good about it. I make this joke often that I traded in one job being at ESPN for 25 jobs. [laughs]

Melissa Harris-Perry: I know that story.

Jemele Hill: You know what I mean? This is the part of this season in my career that I love is that when I want to do something, the only person I have to ask is me. [laughs] That's it. To not have to deal with an email chain, to not have to ask somebody else if I can do something and try to negotiate, that has removed 80% of the stress in my life. It just feels good to operate from a space of autonomy.

Now, the function of my career has changed a lot, is that I was very used to being in traditional media, working for somebody else. Now I work for myself. I'm managing multiple businesses, a production company. I have a podcast network that I've started with Spotify that is specifically for Black women, that centers Black women, that is Black woman-led. That's one of the legacies that I want to leave The Unbothered Network.

We have our first two podcasts on the network launching the first two weeks of November. I'm so proud that I've been able to accomplish this. We're just getting started. This season in my career is about ownership, but it's also about being in this for something much bigger than me and being in this to give other women, other Black women, especially opportunities because it was just really embarrassing to look around a media room or press conference and I'm one of few Black people in there, the only Black woman in there.

I don't want our business to look like that. I'm going to do whatever I can to make sure that it doesn't. It could be a fruitless battle that I'll never win, but I'm definitely going to go down swinging.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Jemele Hill is author of Uphill. Jemele, thanks for so much for joining us today.

Jemele Hill: Thank you for having me. It's a pleasure to catch up with you again, MHP.

[music]

[00:18:42] [END OF AUDIO]

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.