Georgia at the Intersections: Voting Rights in Georgia

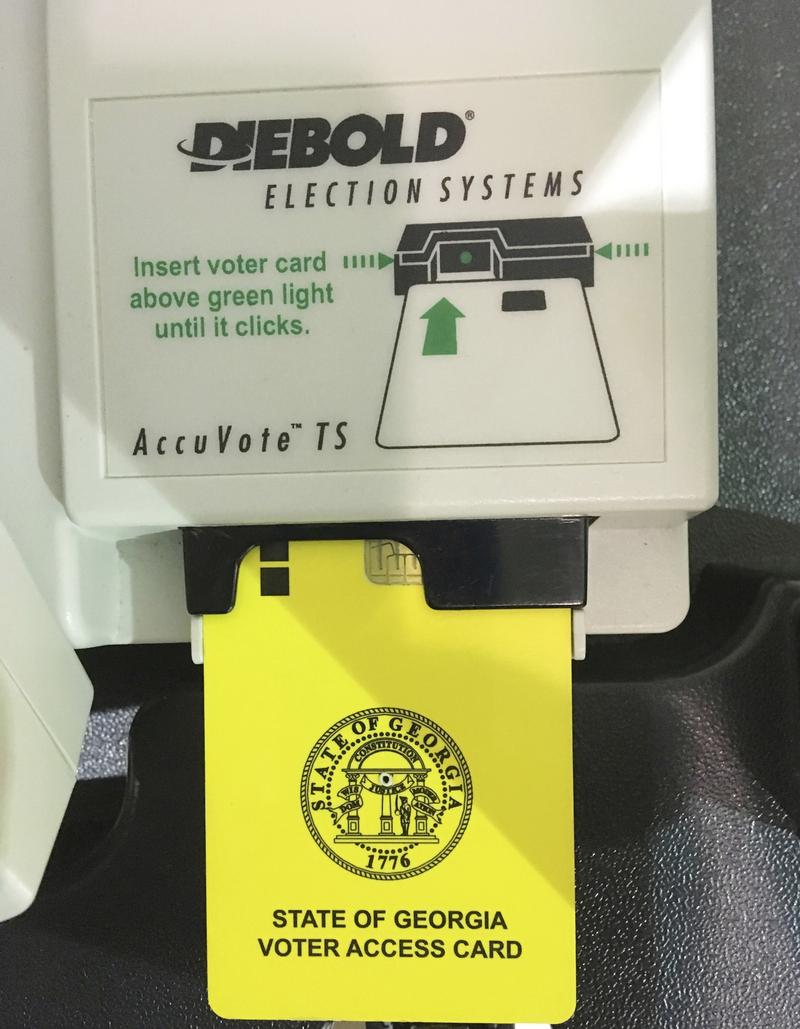

( Mike Stewart / AP Photo )

[music]

Melissa Harris-Perry: Welcome to The Takeaway. I'm Melissa Harris-Perry. It is great to have you with us because I'm excited to tell you about a series of conversations we're calling Georgia At The Intersections. Throughout this year, we're going to bring you some conversations about Georgia, some conversations with Georgians. Yes, we'll even be on the ground bringing you some conversations from Georgia, all with the goal of understanding how the politics, the culture, the legacy, the demographics, and the future of Georgia are shaping our nation.

We're kicking it off today, Groundhog Day, a day of prognostication about winter, a day when we ask just how much longer a biting wind will sting our faces and freeze our fingers. Because it's also the second day of Black History Month, maybe we indulge ourselves a little bit with the words of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. We respond, how long?

Not long. We hope. How much longer will the mornings be dark and the day short? How long? Not long.

We hope. Of course, if we are a bit more honest, we know that no matter what the Groundhog tells us, there are still many days of discomfort ahead. All of this is an apt metaphor for at least one aspect of Georgia politics: voting. See, the state has a way of making you feel like you're living in the same day over and over again. Even though it's a Southern state and pretty warm, there is a chill wind of voter suppression blowing through it. We're asking, how long? You might awake thinking that the dawn has brought something new.

Speaker 2: NBC News now projects Rafael Warnock as the winner in the special Georgia Senate election tonight.

Melissa: But you go to bed and discover it's actually just the same old thing.

Speaker 3: Sadly, Georgia, the same Georgia that sent me and my brother, us off to the Senate, not the people of Georgia, partisans, state politicians have decided to punish their own citizens for having the audacity to show up.

Melissa: Yes. After Georgia sent two Democratic senators to Washington and handed the state's electoral college votes to Joe Biden, the Republican-controlled legislature in Georgia passed restrictive voting legislation that limits mail ballot drop boxes, add strict new ID requirements for mail ballots, and gives voters less time to request mail-in ballots. A recent report by Mother Jones shows that voting restrictions have already made it harder for Georgia voters to cast a ballot because during the municipal elections in November of 21, Mother Jones found that Georgia voters were 45 times more likely to have their mail-in ballot applications rejected than just the year before.

According to the voting rights group, Fair Fight Action, Black voters who make up a third of the electorate in Georgia accounted for half of all the rejections. Again, on this Groundhog Day in Black History Month, we think about the question, how much longer. After completing the March from Selma to Montgomery for our voting rights, Dr. King asked how long, and a hopeful crowd responded not long. As we turn our attention to Georgia, the battle for fair access to the vote does indeed seem far too long. The late Congressman John Lewis who represented Georgia was the youngest person who spoke at the March on Washington full of determination. He promised that the struggle would continue.

John Lewis: Let us not forget that we are involved in a clear social revolution where there's a political party that will make it unnecessary to March on Washington. Where is the political party that would make it unnecessary to march in the streets of Birmingham? We do not get meaningful legislation out of this country, we are marked through the South, through the streets of Jackson, through the streets of Danville, through the streets of Cambridge, through streets of Birmingham."

Melissa: Nearly sixty years later, they can feel like a voting rights Groundhog Day.

[music]

Melissa: Right back where we started. Ari Berman is senior reporter at Mother Jones covering voting rights. He's also author of Give Us the Ballot: The Modern Struggle for Voting Rights in America. Ari, as always, welcome to The Takeaway.

Ari Berman: Hey Melissa, great to talk to you again. Thank you.

Melissa: Is anything different or is this just the same old, same old in Georgia with the voter suppression?

Ari: Well, things are different because Georgia elected a Black senator and a Jewish senator and has a Black woman running for governor. This is clearly not 1950s Georgia, but a lot of the same dynamics are unfortunately there, which is that Georgia is at the cusp of major changes. There's huge demographic changes going on. It's now a majority-minority state, and we're seeing a vicious white backlash play out. One of the main ways the white backlash is playing out is how it's played out historically, which is trying to prevent these new constituencies, trying to prevent communities of color from voting. There's at least some evidence that it seems to be working.

Melissa: How do you respond to folks who say look, "Okay, we see elevated rates of rejection for mail-in ballot applications from Black folks, but there's still plenty of White folks also getting their ballots rejected"?

Ari: [chuckles] The most disturbing thing is that ballots are being rejected in the first place, no matter who's being affected by them. First, I just go through the numbers. I cover voting rights for a living and I was surprised to see how many ballots were rejected, that there was a 45 times increase in mail ballot rejections, and people ultimately not voting in the local elections in 2021 compared to 2020. This was hard data of disenfranchisement.

I listened to an entire debate about voting rights in the Senate where Republicans said over and over, "Nobody is being disenfranchised," and we had absolute hard data of people being disenfranchised, where you can see how it's happening and why it's happening, and then you see that there's disproportionate rates of disenfranchisement, that Black voters are more likely to be disenfranchised than white voters, that young voters are more likely to be disenfranchised than older voters, and you see, this is exactly what people worried about when Georgia passed its sweeping rewrite of its voting laws last year following the elections of Warnock and Ossoff to the Senate and Joe Biden carrying the state in November 2020.

Melissa: Just exactly that point that in 2020, we saw a fairly surprising blue wave coming straight through Georgia there. The other piece of this there is being able to cast a ballot, but there's also a question of whether or not your vote weighs as much as every other vote. That's really a redistricting question. What are those Georgia maps looking like?

Ari: Well, what's happening is Georgia Republicans are repelling the blue wave. We saw in 2020 and early 2021 through the redistricting process. They've drawn congressional maps that will give their party 65% of seats, no matter which way the state trends. There was going to be 9 out of 14 districts are going to be Republican based on how the districts were drawn. They very blatantly dismantled a district of a Black woman, Lucy McBath, from suburban Atlanta. She was the only incumbent member of the Georgia congressional delegation who had her congressional seat dismantled.

I don't think that's a coincidence either that they're not just going after Black voters in terms of casting ballot, they're going after representation for Black voters and trying to get rid of a Black woman who has become quite prominent in the state. The same thing is happening at the state level. The same thing is happening at the local level. You have efforts now at the local level for Republicans to take more power in counties in Atlanta that are trending blue. I think there's a multi-pronged attack on voting rights in Georgia. It's both making it harder to cast ballot, but it's also predetermining who actually wins elections based on how maps are drawn.

Melissa: McBath, of course, is such an interesting case for so many reasons. People may remember, she is among that group of women known as the Mothers of the Movement. She lost her son, Jordan, to gun violence back in 2014. The seat that she was holding had been Newt Gingrich's seat. This is like evidence of how different the demographics of Georgia are right now.

Ari: Yes, it's a really amazing story. This was a quintessential white flight Republican seat held by Newt Gingrich for so many years, for 20 years. What happened is this area outside of Atlanta and the Northern suburbs started trending bluer, became more diverse. You had more moderate white voters, you had more voters of color moving to the suburbs that helped elect McBath, who was a political novice but got involved in politics after her son, Jordan Davis, was murdered by a white man in 2012. She ran for office. When she won in 2018, that in many ways laid the groundwork for the elections of Warnock and Ossoff and showed that there was this multiracial constituency out there.

For them to just blatantly dismantle her district was so telling of what their strategy was. What they did basically is they drew the district from Metro Atlanta all the way up to the Appalachian mountains, and they added three overwhelmingly white counties, including one county, Forsyth County, that actually made all Black citizens leave the county in 1912 after a Black man was lynched. They forcibly removed more than a thousand Black residents in an unbelievable instance of ethnic cleansing. That was one of the counties that was added to Lucy McBath's district. This is saying the quiet part out loud pretty loud.

Melissa: I'm assuming that back in 1912 when that happened, that it wasn't just a request to evacuate, that that was also again done at gunpoint. You have that question of weaponry of guns of that racial history in the south.

Ari: That's a really good point. I hadn't thought about it that way, but yes, they didn't leave voluntarily. A Black man was lynched and they were told to go, and I think the not-so-subtle intimidation was, there will be many more like you if you don't leave.

Melissa: As we look at Georgia, as we look at this moment, I don't want to miss so, that the question of redistricting bipartisan gerrymander is something that Democrats do as well. We see Democrats drawing districts that are beneficial to them. I wonder if the challenge here is that in a place like Georgia, the partisan identity maps on to racial identity so closely.

Ari: It is a challenge, and it's true that both sides are doing partisan redistricting. It does feel like we're in a race to the bottom here where Democrats see Republicans aggressively gerrymandering in places like Georgia and Texas and they say, "We need to aggressively gerrymander in places like New York. Otherwise, it's not going to be a fair fight."

Then, it just becomes both sides trying to out gerrymander the other, which is exactly why Democrats in the Senate wanted to pass legislation banning partisan gerrymandering altogether in the Freedom to Vote Act so you wouldn't have this, so it would apply equally to both red and blue states, but in the absence of federal legislation banning partisan gerrymandering, we're going to see a race to the bottom in terms of who can gerrymander more.

Even though I think Democrats generally speaking are less comfortable with gerrymandering than Republicans are, they're still willing to do it in certain places. I think one of the mistakes we often make though is looking at gerrymandering only through partisan terms, who's getting more seats as opposed to looking at it in terms of fair representation, which is I think why it's really important what you brought up earlier about Georgia.

This isn't just about Democrats or Republicans winning, it's about whether the maps themselves reflect the diversity of the states, particularly in these fast-changing Southern states that are overwhelmingly held by Republicans. What we're seeing over and over in Texas, in Georgia, in North Carolina was that communities of color comprised all of the population growth in these states over the past decade, but actually, there were more white seats than majority-minority seats which doesn't make a whole lot of sense in terms of mapping how these states actually look.

Melissa: Ari Berman is senior reporter at Mother Jones and author of Give Us the Ballot: The Modern Struggle for Voting Rights in America. Ari, thanks as always for joining us.

Ari: Thanks so much, Melissa.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.