Spanish Flu

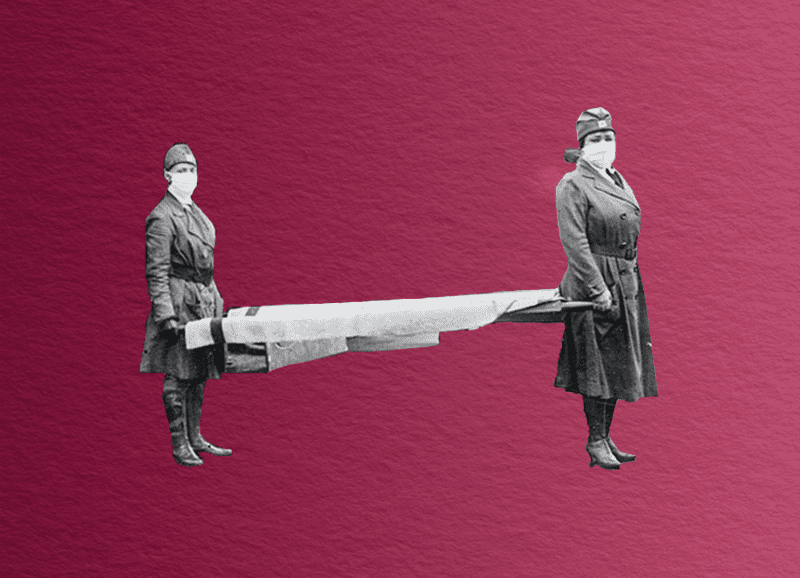

( Library of Congress )

[MARCHING BAND MUSIC PLAYING]

JOHANNA MAYER: On September 28, 1918, the city of Philadelphia was ready to party. The United States was in the final stretch of World War I. And Philly, like a bunch of other cities, wanted to raise some money for the war efforts. So they decided, why not have some fun? Sell some war bonds with the parade?

And they were ready to pull out all the stops. Marching bands? They had them. Uniformed troops, military planes on grand display, a full two miles of floats and flags and some much-needed good spirits. But this parade would turn out to be a colossal mistake because something else was snaking through the city that day-- a virus that people called the Spanish flu.

From Science Friday, this is Science Diction. I'm Johanna Mayer. Today, we're talking about the Spanish flu and how it really wasn't Spanish at all.

When this flu pandemic first struck in the US, no one realized that that's what was happening. It was the spring of 1918. And across the country, young soldiers were crammed together in military training camps, getting ready to go fight the Germans.

And it was in one of those training camps that the virus first showed up. Over the course of just three weeks, over 1,000 soldiers were hospitalized with aches, chills, a high fever. And from there, it quickly spread.

Over the next couple of months, it hit more than a dozen of these training camps. But the vast majority of soldiers recovered by summer. And it all basically died away. And everybody could get back to what they really cared about-- the war.

A few months passed. And then it came back. And this wave was much, much deadlier. And it moved fast.

Science Diction is produced for your ears. If possible, we recommend listening to our episodes. Important things like emotion and emphasis are often lost in transcripts. Also, if you are quoting from an Science Diction episode, please check your text against the original audio as some errors may have occurred during transcription.

In the summer and fall, the virus hit nearly every continent-- Europe, Africa, Asia. It got as far as New Zealand. In early August, it hit the US, starting in Boston and quickly spreading west. In Philadelphia by late September, there were already hundreds sick. And it was then, in the middle of what was shaping up to be a horrific global pandemic, that Philadelphia decided to go through with this big, fancy parade.

I don't know about you, but I have been having actual nightmares about being in crowded places. Just talking about a parade right now is making me nervous. So why would Philadelphia decide to go through with this?

Well, first of all, a lot of cities were throwing parades like these that fall to sell bonds and fundraise for the war. And most of the people who are sick in Philly were sailors. Only a handful had died at that point. And the Navy assured everyone that cases were slowly but surely declining. The situation was in hand.

So Philadelphia had this choice to make-- cancel the parade and risk looking like you've not only overreacted, but you've also skimped on doing your part for the war effort, or go forward and see what happens. So they went forward.

[PEOPLE CHEERING]

About 200,000 people crammed onto Philadelphia sidewalks, all literally breathing down each other's necks.

Three days after Philadelphia's parade, every single hospital bed was full. By the end of the week, 45,000 people were infected. A month later, 10,000 were dead. Across the country there were stories of public nurses entering tenement buildings and finding entire families dead, stories of listening to the endless clomping of horse-drawn hearses going back and forth all day long.

In one town in Pennsylvania, they turned a high school into a makeshift funeral parlor. They'd place the coffin by the window, draw the shades up, give the grieving family a chance to safely view from the sidewalk, then the shades would go down. And they would bring out a new coffin to take its place. Shades up. Another viewing. Shades down. Another body. And on and on, all day.

These types of horror stories? These are not things that you want to broadcast to your wartime enemies. Remember, this new influenza started with the troops. American, French, German soldiers-- they were all dropping like flies. Their enemies didn't need to know about that, nor did the patriotic citizens who were doing all they could to keep up morale. So newspapers buried the stories. Or they flat-out censored them-- kept their reporting to a minimum.

One country that didn't have to worry about any of that was Spain because they were neutral in World War I. So when this strange new virus began circulating through the country, causing people to collapse in the street, even infecting the Spanish king, a newspaper in Madrid did what any paper would do under normal circumstances. They reported on it. Spain was simply the first place to regularly publish stories about this flu. And thanks to that, it got slapped with the name "the Spanish flu," and it stuck.

But the pandemic did not originate there. It wasn't even the hardest-hit place. Even today, experts aren't totally sure where the outbreak originated. Some say China. Some say the American Midwest. Others say maybe France. But they're pretty certain about one thing. It was not Spain.

Now as far as we know, Spanish-Americans or Spanish-speaking people in the US didn't become targets of attacks the way that Asian-Americans are now with coronavirus, maybe because even then, it seems like kind of a lot of people understood that this virus didn't actually come from Spain. Or maybe because people here were already very preoccupied with hating the Germans.

SPEAKER 1: Only the hardest blows can win against the enemy we are fighting.

SPEAKER 2: We could not believe that Germany would do what she said she would do.

SPEAKER 3: And unmindful of the friendship of America, that we still hear the piteous cries of children--

JOHANNA MAYER: They just really weren't looking for another enemy. There's a newspaper article from the time calling the flu "the German germ." Some even accused Germany of deliberately spreading it. Although in Germany, soldiers called it "the Flanders fever."

In Poland, it was "the Bolshevik disease." In Madrid itself, they called it "the Naples soldier." So everyone, at the end of the day, had their favorite scapegoat. The only criteria was that it came from someone else, not you. So it seems like Spanish flu didn't necessarily promote anti-Spanish sentiment.

But sometimes what you call a virus very much does matter, especially when people are on the prowl for a scapegoat. Trump calling coronavirus "the Chinese virus"-- kind of a big deal when people are already being racist against Asian-Americans and blaming them for this pandemic. Naming a disease after a place or a group of people-- it's just not cool, which is why a few years back, the World Health Organization strongly advised that we cut that out.

They also suggested we stop naming diseases after animals. Remember the swine flu pandemic in 2009 and how officials tried to get everyone to switch to calling the virus by its official science-y name, H1N1? It didn't work.

SPEAKER 4: This one-year-old pig has no idea this might be its last day. Along with the other pigs in this pen--

JOHANNA MAYER: That year, Egypt sent all 300,000 of the country's pigs straight to the slaughterhouse, which made no sense because, first of all, swine flu didn't come from those pigs. Researchers traced it to pigs in North America. But also, once humans got it, we were just passing it between each other. That's how the pandemic spread, not through pigs.

Back to the Spanish flu, which wasn't really Spanish. In the fall of 1918, the situation in Philadelphia was bleak. 900 miles away in St. Louis, Missouri things looked really, really different. In early October, a single family in St. Louis got sick. Just two days later, the health commissioner made a sweeping order. Shut the place down.

Schools and billiard halls-- closed. Movie theaters-- dark. Even church services, public funerals, open-air meetings-- all immediately suspended.

And yeah, people were cranky about it then, too. Businesses were super anxious to reopen. People were not pleased that the football season was canceled. But at the end of the day, St. Louis emerged from this thing with half the death rate of Philadelphia.

So how did St. Louis have that foresight? Well, one factor is that, like this coronavirus, the main wave of the 1918 pandemic began on the coasts and worked its way inwards. So St. Louis could hear about what was happening on the East Coast before it reached them, giving them a little bit of a head start.

And the other thing was that officials listened to health experts. The mayor of St. Louis had a pretty solid working relationship with the city's commissioner of public health, Dr. Max Starkloff. And when Dr. Starkloff recommended that they close everything, officials said OK, Doc. And the city shuttered.

But it wasn't a completely flawless execution. St. Louis made the mistake that everybody is worried about making today. It lifted restrictions too early. Cases spiked, and they had to shut down again.

[PIANO MUSIC PLAYING]

So how does a pandemic end? Without a vaccine, there's no magical switch that'll flip, instantly transporting us back to our pre-virus days. And in 1918, they didn't have a vaccine. So when it seemed like cases were subsiding, they tiptoed back to normalcy.

On October 30, 1918, one month and thousands of deaths after Philadelphia's disastrous parade, the doors of the city's movie theaters and saloons creaked back open. Schools and churches were next. A couple weeks later, World War I finally ended, and everyone flooded the streets to celebrate. Over the next few months, cities across the country were slowly doing the same thing-- ditching their masks, reopening their cities, the war and the worst of this pandemic behind them.

The global pandemic killed an estimated 50 million people before it ended. But it did eventually end. The virus itself didn't go away. It kept evolving, mutating, mixing with other viruses. And its viral descendants live on as our garden-variety seasonal flu.

So the virus that caused the 1918 pandemic-- in some ways, it's still here. But of course, we don't call it the Spanish flu. We call it by its technical, World Health Organization-approved, very unsexy name, H1N1. Yep, that swine flu from 2009 is another descendant of the 1918 flu.

But here's the weird part. There was a moment when we almost got rid of these strains for good. In 1957, they disappeared in humans for 20 years. They were just nowhere to be found. They missed the '60s--

NEIL ARMSTRONG: That's one small step for man.

JOHANNA MAYER: --the rise of the Beatles--

THE BEATLES: (SINGING) I want to hold your hand. I want to hold--

JOHANNA MAYER: --almost all of the Vietnam War.

SPEAKER 5: The Vietnam struggle goes on.

SPEAKER 6: The marchers, representing over 100 peace groups and a delegation of hippies, chanted anti-Johnson slogans.

JOHANNA MAYER: And then in 1977, one of these strains suddenly reemerged. It was first reported in the Soviet Union. And yep, you guessed it-- people started calling it "the Russian flu." Classic. And this virus looked just like the strains that had vanished 20 years earlier.

So scientists don't think that it was just lying around in wait this whole time. They think it was something much more frustrating and much more mundane. The most popular theory goes it was just a lab accident. That some researcher someplace had it in a freezer and accidentally let it out.

No one's exactly sure what happened. But one thing we do know for sure is that it's back. And we live with it.

[PIANO MUSIC PLAYING]

Science Diction is produced and hosted by me, Johanna Mayer. Our producer and editor is Elah Feder. We also had some story editing help from Nathan Tobey and fact-checking help from Michelle Harris. Our composer is Daniel Peter Schmidt. Special thanks this week to Alan Kraut and Chris Naffzinger.

One other thing-- we've been getting so many nice reviews lately on Apple podcasts. Biologistico called the show "a word nerd's treasure." Navajo Jane said that it is "just long enough to make some lunch and learn something cool." That is exactly what we are aiming for.

These kinds of reviews really help us. And they've honestly been a nice, bright spot in the middle of a tough time. So if you feel inspired to leave one, we would love that. We will be back soon with more episodes not related to the pandemic. We are very excited to talk about anything but.

[PIANO MUSIC PLAYING]

Copyright © 2020 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/