The Rise Of The Myers-Briggs, Chapter 2: Isabel

JOHANNA MAYER: Science Diction is supported by Audible. The new plus catalog makes Audible memberships so much more valuable and gives all members the chance to listen to and discover new favorites and new formats. Like the exclusive Words + Music series. Or a podcast that you never considered before. Visit audible.com/diction or text Diction to 500-500.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

SPEAKER: Listener supported. WNYC Studios.

JOHANNA MAYER: Just a note that this is chapter 2 of our three part series on the Myers Briggs. So if you haven't heard the first chapter, we recommend going back and listening to that first. OK here we go.

ISABEL BRIGGS MYERS: Now to begin, I'd like to ask the first question. But I'll forget our conversation going. And that's one that many people ask me. How did you come to create the Myers Briggs type indicator?

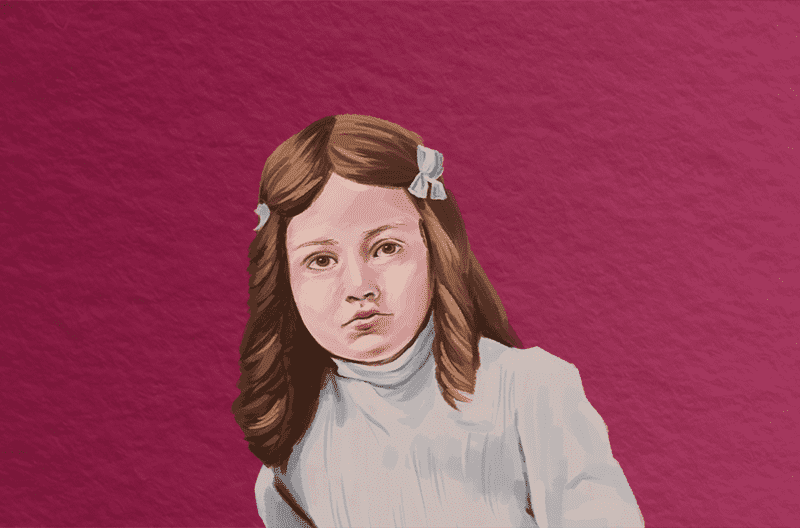

CHRIS EGUSA: It's a video from 1977. Isabelle Briggs Myers is 79 years old at this point. She's seated against a red brick wall surrounded by four Myers Briggs devotees. There's a bit of construction in the background but they are totally focused on Isabel. Taking turns asking her questions. And they want her to tell the story again. How did it all start?

ISABEL BRIGGS MYERS: Well, I suppose the very beginning of it was that I fell in love with a man who was different from me. Three of the four preferences that my type and this was noticed by my family that there was something different. Admirable, but different.

CHRIS EGUSA: His name was Clarence but everyone called him Chief. At first, he threatened to drive a wedge between Isabel and her mother. But eventually their marriage is what would convert her to Katherine's gospel of type.

JOHANNA MAYER: But where Katharine's a religion of personality Isabel saw a product with world changing potential.

ISABEL BRIGGS MYERS: And now, as most of you know, it has become one of the most widely used instruments for everyday people.

LARRY STRICKER: I just find it curious. It's widely used in industry. It's even used in the military. Just everywhere.

JOHANNA MAYER: This week, in chapter two of our three-part series, Isabelle takes her mother's theory of type and turns it into the world's most popular personality test. For better or for worse. From Science Friday, this is Science Diction. I'm Johanna Mayer.

CHRIS EGUSA: And I'm Chris Egusa. Today, the Rise of the Myers Briggs. Chapter 2, "Isabel".

JOHANNA MAYER: In the summer of 1915 in Washington, DC, Isabel was getting ready to head off to college. She'd chosen Swarthmore. 100 miles away from Katherine and the cosmic laboratory of baby training. And it seemed like Isabel would have nothing to do with personality typology. That was her mother's passion project, not hers.

Isabel was making her own life. She wrote in her diary that she was ready to quote, "shake things up". She did the usual college stuff. Got a little rowdy, maybe a tad unladylike. And then she met the man she'd eventually marry. Chief, a good looking farm boy from Iowa who turned out to be a socialist.

Katherine did not approve. Maybe earlier her mother's disapproval would have reeled Isabel right back in. But not now. Isabel stuck with her new husband all while Katherine watched, horrified. All the training Katherine put her through. All the no no drills couldn't compete with the youthful rebellion.

But in the end, she came back to her mother. And by the '40s personality typing was as much a passion for Isabel as it had been for Katherine. She gave a few reasons for why it mattered.

That it was World War II and increasing human understanding was needed now more than ever. And that during the war people were being assigned to jobs they hated. Wouldn't it be better for morale if they got jobs that fit their types? But the reason she gave most often was that it was because of Chief. How different he was from her.

ISABEL BRIGGS MYERS: Where I'm intuitive he's sensing, where I'm feeling he's thinking, and where I'm perceptive he's judging, as I just confessed. And this has worked beautifully with the help of [INAUDIBLE] of our marriage. I don't think it would have been anywhere near such fun or so good if he had known about types.

JOHANNA MAYER: By the time of this recording they've been married for 60 years and Isabel is putting a positive spin on it. But those early years had been tough. Sometimes Chief even suggested they get divorced. And it sounds like her mother's theory of types helped her accept his differences. It might have actually saved their marriage. She set to work.

CHRIS EGUSA: In 1943 Isabelle designed the first version of the indicator. And instead of following Jung's ideas exactly, she went off-script. Now Katherine had borrowed much of Jung's language. Introverted versus extroverted, sensing versus intuitive, thinking versus feeling. But Isabelle added a fourth dimension-- judging and perceiving. J and P.

Judging types, she said, try to control life. Perceiving types are more flexible. While Katherine approached personality typing as an almost sacred art, Isabel's indicator was a straightforward questionnaire. And some of the early questions are charmingly dated. Things like, do you a very much enjoy stopping at soda fountains or B usually prefer to use your money for other things?

And just like her mom, Isabel started collecting data with the subjects most readily available to her. Her kids, Ann and Peter, and all their classmates. But maybe the most important choice she made was to focus on the positive like her mother had.

ISABEL BRIGGS MYERS: Well from the very beginning we felt that the types should be characterized by what they have rather than by what they lack. Of course, it stands to reason that if you're much better in one thing than in another then you're not as good in the other as you are in the first thing. To find well on that the valuable and constructive things are the things that people have.

CHRIS EGUSA: You should be able to read your Myers Briggs description and think, yeah, who I am is different and it's good. And that is possibly the most appealing thing about the indicator. There are no good types or bad types. And you don't have to be anyone else. Just be the best version of yourself.

You'll hear that from a lot of people who take the test. It makes them feel good about themselves. People proudly display their four letters on dating profiles, on resumes, on Twitter bios. They join Facebook groups just for their type. For my type, INFP, I found a Facebook group with over 20,000 members. And it's not the only INFP group.

JOHANNA MAYER: But some see something sinister in the test and its history. The very idea of sorting people into categories, historically, it's got a pretty abysmal track record when taken to extremes. But there's more. Katherine Briggs had some eugenicist beliefs and it sounds like Isabel did too.

MERVE EMRE: So for instance, she doesn't believe that anybody with an IQ less than 100 is worth typing.

JOHANNA MAYER: Merve Emre, author of The Personality Brokers.

MERVE EMRE: Because she doesn't believe they have the intellectual capacity to express personality preferences. There are several interesting letters in the archive where corporations write to her and say, could we test someone who drives one of our trucks? And she says no, no. I don't think a truck driver is worth testing.

JOHANNA MAYER: And Merve sees a recurring theme in Isabel and her mother's work. Purity, including in some cases, racial purity. Before she turned her full attention to the Type Indicator, Isabel had a brief career as a mystery writer. Her second novel was called Give Me Death.

MERVE EMRE: Its whole premise is that there is a wealthy, Southern aristocratic former plantation-owning family where the members of the family start to kill themselves because they are led to believe that they have one drop of African-American blood running through their veins.

JOHANNA MAYER: The Myers Briggs foundation has a statement about the book on their website arguing that writing a book about racist characters doesn't make the author racist. Which it doesn't, but Merve read the book and she doesn't buy their take. She says the novel is fixated on purity of blood and what it means to be impure.

MERVE EMRE: The question is, are you being critical of that or not? And I do not think that this is a novel that is critical of it.

JOHANNA MAYER: Still, when we try to make sense of Isabel and her writing historical context matters.

MERVE EMRE: This is a novel that comes out right before Gone With The Wind. And how the early '30s are this moment of romanticizing the plantation and of romanticizing the legacy of the South. And so I'm not saying that she was uniquely bad. There were plenty of other people who were doing this. But I do think that it is troubling, and it's especially troubling because its author then goes on to design an entire system of people categorization.

CHRIS EGUSA: By all measures, Isabel's indicator was a tribute to her mother. She even named it Briggs Myers, insisting her mother's name came first. But Katherine herself wasn't impressed. These answer choices Isabel was forcing on people, a simple yes or no? Please, type is never so simple.

But Isabel was already running with it. It didn't take long for her to find clients. Within a few years of launching the indicator she'd landed contracts with government bureaus, colleges, and even corporations. And these corporations saw a way to turn this test into profit.

For instance, Isabel said that extroverted intuitive types were risk takers. For an insurance company that might mean they're more of a liability. So charge them more, right? And then she got an invitation. She told a friend it was manna from heaven but it almost proved her undoing.

The invitation was from the Educational Testing Service. The Educational Testing Service, or ETS, is the company that runs the SATs. It's the place where she roamed the halls with her homemade energy drink and the employees called her, "that horrible woman". The founder and head of the company had taken a shine to Isabel. He saw the potential in her questionnaire.

He hired her on as a consultant ready to shepherd her indicator into the world. And as much as the men of ETS ridiculed her, Isabel was undeterred. She knew what she had. And just when it seemed like everything was falling into place, along came Stricker. Larry Stricker. Years later, Isabel's collaborator, Mary McCaulley, recalled this saga at a conference.

MARY MCCAULLEY: And she said to me, I felt like he came over the woods. I sent for the Marines and they came over the woods shooting at me. She had a file folder that said Stricker, damn him.

CHRIS EGUSA: Stricker, damn him. Larry Stricker was a 27-year-old kid fresh out of his PhD program in social psychology who'd just started at ETS. And his job was to create a manual for Isabel's indicator. He worked on it for months. And when he finally shared his draft Isabel was not pleased.

ISABEL BRIGGS MYERS: When the thing came out even Stricker himself admitted it was not a manual. It was a critique of the Type Indicator done in the tradition of the graduate school he had come from. In which the more faults you could find with a piece of work the better critique you were. And it was this pure and simple. And I was annoyed.

CHRIS EGUSA: To Isabel, Larry was a never ending thorn in her side. A snobby PhD who was hell-bent on destroying her life's work. Larry Stricker, damn him.

LARRY STRICKER: Damn him, right. Yeah, that's going to be on my tombstone.

CHRIS EGUSA: We called Larry for this story. He's 88 now. We were honestly a little nervous after hearing Isabel's description of the guy. But he was nice. Happy to answer all of our questions and talk about the old days. And he remembers that time pretty differently from Isabel. Back in September of 1960 he was just starting his career.

LARRY STRICKER: I was a young psychologist, a scientist. And I was interested in doing this project and doing the best I can.

CHRIS EGUSA: And things started off well. At first he and Isabel got along fine. Unlike his colleagues, Larry didn't dismiss her. Even though she didn't have a background in statistics or psychology, Larry says she'd figured out ways to do things on her own. And what she came up with was a lot like what someone with formal training would have done.

He met Isabel on his very first week on the job. And immediately, of course, Isabel did what she did with everyone that crossed her path. She got him to take the test.

LARRY STRICKER: And I took it and I was in INTJ. Introverted, intuitive, thinking, judging. And she immediately reported this to Chauncey.

CHRIS EGUSA: Henry Chauncey, the boss.

LARRY STRICKER: And he sent a memo saying, well it's about time we have a judging type on this project. And I think he lived to regret those words.

JOHANNA MAYER: Larry had a few issues with the indicator. First, it's supposed to be Jungian but he said it didn't really align with Jung's theory. Isabel's definitions of extroverted and introverted, for example, slightly different than Jung's.

And second there's the whole idea of sorting people into distinct types. So like height. Some people are tall, some people are short. But most people fall somewhere in the middle. And to Larry, Isabel's theory is like saying, there are tall people, and there are short people, and that's it. Extroverted or introverted, feeling or thinking.

But when Larry looked at the data these categories didn't make sense. Most people were somewhere in the middle. And these were just a few of his complaints.

CHRIS EGUSA: Maybe Larry should have seen it coming. He was, after all, criticizing Isabel's life's work. But his relationship with her took a big turn. He says at one point she even tried to get him fired. And her reaction really got to him.

LARRY STRICKER: I live nearby in Princeton. And it got to be when I knew she was coming, I would stay home. And when I drove in into ETS my stomach would start burning because it was so stressful. Anyway. I was a sensitive young man and it just bothered me.

JOHANNA MAYER: The next few years were hard for Isabel too. Not only was young Larry Stricker undermining her life's work, but Isabel's family was descending into crisis. Both her kids were on the verge of divorce. Her father died, and her mother was dying too.

And in a way that seemed particularly cruel for a woman who devoted her life to understanding the mind, Katherine had dementia. And then ETS let Isabel go as a consultant. She was costing them a lot of money and with the relentless critiques from Larry and others at the company, she just lost her credibility with them.

Although, maybe she'd never had it. And this was the moment that the Myers Briggs Type Indicator could have faded into obscurity. But as we know, that's not what happened in the end.

LARRY STRICKER: I just find it curious. It's widely used in industry. It's even used in the military. It's just everywhere.

JOHANNA MAYER: Larry thinks the positive descriptions have a lot to do with that. But also, that anyone can see themselves in this test.

LARRY STRICKER: It's like you go to a Chinese restaurant and waiter at the end brings the fortune cookies. And the fortune cookies says, you are not always in touch with your feelings. I say, my god, how did the waiter know that?

There's a famous study where a psychologist gave his students some kind of personality test. And then he just randomly gave people results that were not theirs. And they all said, oh, wow. Boy, that really describes me.

JOHANNA MAYER: It's called the Barnum effect. And it basically means that a description of something is so vague that anyone can see themselves in it and just latch on. It's kind of the same deal with horoscopes. It's named after the classic showman, PT Barnum, a man famous for his hoaxes.

Because the psychologist who coined the term, Barnum effect, was disturbed by personality tests and how easily they duped people. But is that what's going on here? Is this all just smoke and mirrors?

CHRIS EGUSA: Larry's criticisms are significant but they aren't necessarily fatal to the test. Maybe the test doesn't stay true to the Jungian theory. But so what? As long as it works, who cares? And so what if we're on a continuum? Buckets can still be useful. Take the height example.

Say you're assigning people to stock grocery store shelves. Anyone in the tall bucket stocks the top shelves. Anyone in the short bucket does the lower ones. Sure, there are lots of people who aren't strictly tall or short. But it's better than assigning people at random, right? An oversimplification but maybe a useful one.

So is the Myers Briggs test useful and does it measure something real about who we are? Or is it a fortune cookie? Because, if it's a fortune cookie, that's a problem. The Myers Briggs is everywhere. What if people are hiring only ESTJs or only looking to date INFPs? What if someone thinks, these are my four letters. They define who I am and all I can be. And those letters don't mean anything?

Next week, our final chapter. Myers Briggs, what is it good for?

JOHANNA MAYER: This episode was produced by me, Johanna Mayer. And--

CHRIS EGUSA: Chris Egusa.

JOHANNA MAYER: And--

ELAH FEDER: Elah Feder. Our music was composed by--

DANIEL PETERSCHMIDT: Daniel Peterschmidt--

JOHANNA MAYER: --who also mastered this episode and helped with archival research. We have fact checking help from Cosmo Bjorkenheim. Peter Geyer provided us with archival audio.

As always, you can find transcripts and more at sciencefriday.com/diction. And Thank you to all the reviewers on Apple Podcasts. Layla Eller, nickname 8375, we see you. Nadja Oertelt is our chief content officer. And she has decided to stop speaking and start communicating with her family exclusively through the art of mime.

ISABEL BRIGGS MYERS: And this was noticed by my family that there was something different. Admirable, but different.

JOHANNA MAYER: See you next week with chapter 3. Science Diction is supported by Audible. With an audible membership, you can choose from thousands of titles to listen to offline anytime, anywhere. The audible app is free and can be installed on all smartphones and tablets.

You can listen across devices without losing your spot. The new plus catalog makes audible memberships so much more valuable and gives all members a chance to listen to and discover new favorites and new formats. Like the exclusive Words + Music series or a podcast you've never considered before. Visit audible.com/diction or text Diction to 500-500. That's audible.com/diction or text Diction to 500-500.