4. The Chunited States

Chris Garcia: This is Scattered, Episode 4.

Chris: Hello?

Ana: Hi!

Chris: Cómo estás, mom?

Ana: Cansada. Me duelen las rodillas. Cuéntame.

Chris: A few days ago, I got something in the mail. Copies of my dad’s medical records from his time at the Metropolitan State Hospital outside of LA. That's where he was committed after trying to kill himself in 1974.

Chris: Um, yeah mom, so quería hablar contigo acerca de estos records que cogí del hospital en Norwalk…

Chris: I finally worked up the courage to call my mom and tell her what they said.

Chris: Pero aquí tengo la nota del doctor y dice que el paciente… es cómo se dice “patient?” El paciente es un hombre de 32 años que habla Español…

Chris: “Patient is a 32 year old male. He’s been depressed for several months prior to this. Patient has been unable to find employment since he immigrated to the U.S. from Spain where he had lived after leaving Cuba….”

My mom, usually talkative, just listens in silence, taking it all in.

Ana: Sí, okay.

Chris: Y que su emotional disturbance...

Chris: “His emotional disturbance seems to date from his imprisonment in a concentration camp in Cuba.”

Ana: Wow. Viste eso?

Chris: All this time, trying to learn about my dad's life, I've had so little to go on. No records from his time in Cuba or Spain, no letters or documents.

So I've been asking my mom, “When did this happen?” “Why did that happen?”

And then digging in. “Are you sure? How do you know?” Almost like I don’t trust her memories of her own life.

It’s worn her down.

And now, I finally have official documents, saying that the labor camp damaged my dad. That it damaged him so badly that many years later, he tried to kill himself. My mom wasn’t imagining things. Her memories -- they’re real.

Chris: Dice la letra también que papi tenía dificultad con el inglés...

Chris: “His language limitation makes it difficult for him to relate his feelings outside his cultural milieu and may have exacerbated his feelings of depression and alienation.”

Ana: Wow. Wow.

Chris: Dice aqui en Mayo 22.

Ana: Wow. Wow.

Chris: But according to the records, dad was admitted on May 22, 1974. Not Labor Day, like she and my sister remembered. It was actually more than three months before Labor Day, which is in September.

Ana: Y no dice qué día salió?

Chris: She asks, “Does it say there what day he was released?”

Chris: Sí.

Ana: Qué día salió?

Chris: Él salió… Perdón. Mayo 28 del ‘75.

Chris: May 28th, 1975. One year later.

Ana: What? Really? Tanto tiempo, papa?

Chris: She says, “Wow, so much time.”

Ana: Wow. Ashh. Si lo dice el papel.

Chris: “Okay, if that’s what the paper says.” I can hear she’s deflated, and a little confused. She’d remembered him being in a psych ward only for a few months.

Ana: Y que bueno que tienes esos records, eh. Tantos años.

Chris: “It’s good you have those records after so many years.”

Chris: Te recuerdas mom que estaba allí por un año y siete días?

Chris: “And now do you remember he was there for a year and seven days?”

Ana: Yo me acuerdo… Nunca se me olvida que fue en Septiembre. Eso le pasó cuando estaba el maratón, el teletón que tenía Jerry Lewis.

Chris: “It happened during the Jerry Lewis Telethon.”

It’s always been a thing in my family. My sister Laura -- Lala -- says she’s never been able to watch Jerry Lewis because of her associations with the day my dad tried to kill himself.

But there was no Jerry Lewis Telethon in May.

Chris: So, tú crees que Lala, cuando Lala estaba hablando de Jerry Lewis…

Chris: I ask if it’s possible she and my sister watched the telethon in the hospital with my dad. Like, after he’d been there for a few months. And somehow Jerry Lewis got stuck in her head.

Ana: No me acuerdo papa. Es que iba mucho tiempo. Era muy desagradable verlo, muy desagradable. Muy desagradable. Era muy... Hacían terapia de grupo. Todas la familias reunidas. Todos los enfermos allí en un salón. Hacían unas terapias durísimas. Durísimas…

Chris: She says, “Maybe, maybe the dates are mixed up in their minds.” She remembers going to visit him. That it was awful. She went to group therapy with him and people would take turns talking. It was very hard… “Durísima,” she says.

Ana: Ay papi...

Chris: How could a year disappear from my mother’s mind, just like that? It’s like her brain shrunk time. Shrunk the painful stuff, so it’s just a blip.

The thought of my dad being alone in a psych ward for an entire year just two months after moving to this country... and my mom having to manage without him… How’d they do it?

Ana: Y que más dice?

Chris: “What else does it say?” she asks.

Chris: Que le dieron medicina.

Chris: It lists these things as his problems.

Chris: Y dice que estaba deprimido.

Chris: “Anxiety and depression. Poor use of leisure time.”

Chris: No le gusta interactuar con otras personas.

Chris: “Does not interact with peers. Low esteem and lack of maturity.”

Ana: Okay…

Chris: Um...

Chris: “Needs to learn a trade to earn a living. Language barrier.”

Ana: Okay.

Chris: Um... Pero dice que él mejoró en todas esas cosas. Y que él aceptó el plan que le dio el doctor.

Chris: But I tell her, “It says he got better.” He took to therapy.

Ana: Me da mucha lástima. Pobrecito.

Chris: “I feel very sad for dad,” she says.

Ana: Okay papa. Lee eso pero ya no me digas ya más porque ya eso me…

Chris: “Don’t tell me anymore.”

Our conversation hangs in silence. And then she says --

Ana: Y allí es donde Touzet lo conoció.

Chris: “That’s where dad met Touzet.”

Ana: Porque Touzet estaba allí. El también venía medio quemado de cuba. Y entonces allí es donde conoció a papi en el hospital.

Chris: “Touzet also came from Cuba with problems, and he met Papi in the hospital.”

To which I say, “Who’s Touzet?”

Rodolfo Touzet: My name is Pastor Rodolfo. Bueno, my name is not pastor. I am a pastor. But my name is Rodolfo Touzet and, ah, I have been a pastor for 42 years.

Chris: Rodolfo Touzet isn’t hard to find. He lives with his wife Sunilda in a retirement community in Bell Gardens, just outside of LA.

Touzet says he used to visit my mom and dad a lot in the years before I was born.

Rodolfo: Pero cómo se parece al padre. Ah, ahora más todavía!

Chris: Sí?

Rodolfo: Sí.

Chris: When we meet, right away, he says I look like my dad, which makes me smile. Touzet is 80 years old and looks like a Cuban Tom Petty…he’s skinny, he’s got big ol’ teeth, shaggy grey hair. And like Tom Petty, he’s a musician -- he’s recorded six albums of Christian salsa music.

Rodolfo: This is my music.

Daniel: Oh great we'll listen in the car. That's perfect.

Rodolfo: Eh, 41 songs.

Sunilda: Hallé lo que buscaba. Fue, que, el primero que cantó.

Rodolfo: You don't believe but I was this.

Chris: He points to the cover of one of his CDs, where he’s decades younger, smiling at the camera, with silky black hair and a latin lover button down. The name of the album is Hallé Lo Que Buscaba. “I Found What I Was Looking For.”

Touzet and Suni have a terrier named Chiqis. She’s very small and drinks café con leche out of a saucer.

The walls of their little apartment are crammed with picture frames. There’s a large photo of Touzet and Suny’s wedding day, a painting of Moses parting the seas, and posters of scripture. Like Psalm 37:4, “Take Delight in the Lord and he will give you the desires of your heart.”

Rodolfo: Ready? Let's pray. Padre, en el nombre de Jesús, esta entrevista es para tu gloria in the name of Jesus. Amén.

Chris: Touzet had only been a Christian for six months when he met my dad.

Rodolfo: Claro, mira, cuando Cristo entra en la vida nuestra, cambia todo… Un, un nacimiento de nuevo total.

[VO: Look, when Christ enters our lives, He changes everything. Everything changes. For 17 years I was an alcoholic. Seventeen years. I smoked marijuana for four years, and I was a cocaine user for three years when the Lord rescued me. When the Lord rescued me I became a new creature. The old had passed away, like the Bible says. I was reborn, and after that, well no alcohol, no drugs, no marijuana, nothing! A total rebirth.]

Chris: With the passion of a new believer, Touzet was visiting patients at the Metropolitan State Hospital, trying to save their souls.

Rodolfo: Oh! Tu papi estaba muy mal. Me recuerdo que no, no hilvanaba bien. No razonaba bien... Me acuerdo que hablaba a veces cosas que no tenían sentido.

[VO: Oh! Your dad was in bad shape. He wasn’t thinking clearly. He wasn’t taking care of himself. He was totally out of it. I remember he was saying things that didn’t make any sense.]

Chris: But every Saturday for about two months, Touzet would sit with my dad.

Rodolfo: Que, que, que, que pues yo creo que hay personas que quizás asimilen más… Era un hombre muy inteligente. Eso sí… Yo no soy médico. Yo soy pastor.

[VO: I think that there are some people who maybe internalize suffering more than others. But, he was a very intelligent man, And he was a very capable man, but I don't know... Like I said, I'm not a doctor, I'm a pastor.

Chris: Um… Mi papá te explicó porque trató a suicidarse?

Chris: Did my dad explain to you why he tried to kill himself? Or what his life was like right before he did it?

Rodolfo: Que no tenía sentido la vida. Que ya él había hecho lo que tenía que haber hecho... Y que ya no tenía sentido la vida.

[VO: He felt like there was no point to life. That he had already done what he had to do. And that life had no meaning.]

Chris: Touzet had his own struggles in Cuba. He says he was sent to a labor camp twice. The first time, for being critical of the Castro regime. The second was for asking to emigrate.

Chris: Y él habló de las dificultades en su vida? Habló del campo en Cuba?

Chris: I ask him if he and my dad talked about the camps, and about how that experience was one of the reasons my dad tried to kill himself.

Rodolfo: Habló de eso, pero nosotros tratábamos de desviarlo... Porque esos recuerdos no se borran nunca… Y yo tuve demonios. Yo fui libre de demonios y tu padre tuvo demonios… Y orábamos por él y ya se le quitó todo eso después.

Touzet: We tried to steer him away from talking about the suicide attempt. But those memories are never erased. I had demons. I was liberated of my demons. And your father had demons. We ministered the word to him. We prayed for him. And eventually he was free of all that.

Chris: No me dijo de su intento de suicidarse.

Chris: He never told me about the suicide attempt.

Rodolfo: Porque no quería que tú sufrieras… que tú supieras.

[VO: Because he didn’t want you to suffer. A father’s heart is protective. And he wanted to protect you from knowing what had happened.]

Yo siempre, ok, desde que conocí a tu padre en el hospital… Y después estuvo sana.

[VO: From the moment I met your dad at Metropolitan State Hospital, I saw a good soul, a good heart and, yes, a mind that was not sane, but that would become sane.]

Chris: I'm not much of a religious person. I'm the guy who when my family says grace, I open my eyes, look around, and sneak a bite of a dinner roll.

But my dad was a believer. He went to church every Sunday. He even had a favorite apostle -- John.

What I didn’t know, until this moment, is how or when my dad found Christianity. It was in that hospital, and it was because of Touzet.

I tell him he had a big impact on my family during a really difficult time. That he changed my dad’s life.

Chris: ...De mi papá y después que tú, te conoció, que tú lo ayudaste mucho y ayudaste a cambiar su vida.

Rodolfo: Amén.

Suni: Amén.

Rodolfo: Un aplauso pa’ Chiquis que se portó ejemplar...

Chris: We give Chiquis the dog a big round of applause for staying quiet during the recording. I thank my hosts for the cafecito and say adiós.

Chris: Smells like Cuban food in here.

Daniel: Um, Chris, what are you putting on right now?

Chris: That’s my producer Daniel.

Chris: Rodolfo Touzet’s… one of his six albums, Rodolfo Touzet “Hallé lo que buscaba.” And it’s 16 songs.

[MUSIC]

Chris: Touzet slaps man! Touzet, he’s got it!

Chris: When my dad was released from the hospital, the doctors determined he’d shown -- quote -- “reasonable improvement in all.”

“All” referred to the problems he’d had when he was admitted, including anxiety and depression, low self-esteem, and not interacting with peers. The doctors noted that he’d received medication, therapy in Spanish, and vocational training in mechanics.

No mention of Touzet. Or of his weekly visits, where my dad talked and he listened. As far as I can tell, no man had ever done that for him. He was my father’s first friend in America.

>>>>>MIDROLL<<<<<

Ana: A ver, Cristian.

Laura: Cristian, habla. Cómo te llamas?

Ana: Cómo te llamas?

Laura: Cómo te llamas?

Chris: Tita!

Chris: On May 13, 1977, at 12:33 p.m., something amazing happened: I was born.

My dad tried to give me the middle name “Angel” -- a clear sign of his conversion. My mom was like, “Christian Angel Garcia? Why don’t we just name him Mr. Bible-Jesus?”

Laura: Di café!

Ana: Di abuelo. Abuelo! Abuelo!

When I was about a year and a half, my family made a Thanksgiving recording for my grandparents who were now living in Miami.

Ana: Abuelo!

Chris: Mami!

Andres: Bueno mi querido suegro… Te quiero desear que pasen un buen Sansgiving…

Chris: My dad says, “My Thanksgiving wish for you is a new house with a new bathroom, so that when grandma does her business, she doesn’t break the toilet!”

Comedy gold.

There's something else you can hear on the recording, in the background. The sound of airplanes... It’s the sound of my childhood.

I grew up in Inglewood, under the flight path of LAX. Little known fact: Steve Martin also grew up in Inglewood. He even went to my Kindergarten. But that was before all the white people left.

Chris: Grew up here in Los Angeles, in Inglewood. You guys know Inglewood? Inglewood.

It was rough when I grew up. And you see funny things in the hood, like weird things. I saw a cholo cry. I don’t see that, I mean have you ever seen a cholo cry? He’s all, he was like Maria, I gave you my heart. I don't know if you've ever seen a teardrop fall over teardrop tattoo. That’s like a solar eclipse, it's a cholo eclipse, because you don’t look at it, it’ll mess up your eyes.

My parents always hustled. So my parents lied about where we lived so I’d go to a better school. They lied, so I could go to school in West Chester. They scrapped, they scrapped all their money into sort of a cheap Catholic school. So I went to a Catholic school, not Catholic... at all. I had to get baptized to go to this school.

The priest is like, hey, where's the godparents? And my dad's like, I'll be right back, comes back with my sister and our 50-year-old family mechanic. You know, my dad’s like, oh okay if I die this smog specialist is your new papi, ok? The lord works in mysterious ways. Play along cabrón, okay?

Chris: See -- that’s hustle.

And so is this: My dad got out of the hospital and started to get his life together. He went to an unemployment agency and got a job at a machine shop in Culver City. He biked there every day.

He and my mom started taking English classes. And my dad enrolled in a trade school to upgrade his skills and become a CNC machinist, which is basically a machinist who works with computers.

The Garcias were seizing the American dream. They loved Reagan, they proudly flew the American flag from the front porch. And if you didn’t get up to sing the National Anthem at Dodgers Stadium, hooo boy...“Eh what’s wrong with your legs? Are your legs communist?”

Then one day in 1980, my dad saw a newspaper ad for a machinist job at a company called Rockwell International. It was the country’s biggest defense and NASA contractor.

Rockwell Recruitment Video: “As you will see in the next few minutes, Rockwell is a very diversified company.”

Chris: He applied.

“A company where people and technology are definitely on the move…”

Chris: I found this old black-and-white picture from the Rockwell years. It’s my dad, with his megawatt smile, flanked by two old white guys in suits. They’re presenting him with a certificate... an award for having -- quote -- “optimized” a machine. I have no clue what that means.

And maybe one of the reasons I have no clue is that I never asked my dad about his job. I barely took an interest.

On Saturday mornings, he’d take me to the California Science Center.

He was a space nerd. He collected NASA pins and patches. He loved the aerospace exhibit. It had all these satellites and rockets hanging from the ceiling, and a flight simulator.

It all bored the hell out of me.

I did like the astronaut ice cream, though. And the computer-themed McDonald’s where you could look through a window and watch as a robot prepared your Mcnuggets. As a fat kid, this is the future I was waiting for.

Anyway, that job at Rockwell made it possible for my dad to give our family a good life. Our fridge was always full, he’d take my mom out on dates. Every year, I’d get a fresh pair of Jordans.

It was the Cold War, and the aerospace business was booming.

Chris: And then...

“...after six and a half years in power, Mikhail Gorbachev confirmed his resignation on television tonight [Russian]...”

“...there is no animosity, the Cold War days are over…”

Laura: And I remember watching it on television as it unfolded and, um, and realizing shortly after that, this is the end of aerospace as we know it in the South Bay.

Chris: My sister, Laura.

Laura: So when you think about Aviation Boulevard and all those companies, you know, one after the other, Northrup, Rockwell, Hughes, and all of that that comes with it.

Chris: McDonald Douglas. Yeah.

Laura: Yeah, McDonald Douglas. I mean that was the, the death of all that.

Chris: In 1991 my dad was laid off from Rockwell. Tons of people were…

“They and numerous defense industry personnel are not losing their jobs because they failed, they're losing their jobs because they were successful in contributing to our winning of the Cold War. They're all winners.”

Chris: My dad was one of those winners.

We sold our house and moved into a little apartment. Our living room was also a dining room and also the computer room. We went from living in a neighborhood surrounded by families to living next to a Burger King and a 22 year-old burn-out named Scott.

Laura: And I remember my dad coming up to me and saying, Laura, can you help me? I need to create resumes that really accentuate my machinist skills and I'm feeling like I'm, I'm not going to be able to keep up. I can't be what they want me to be.

Chris: He asked me for help with his resume, too. He must have been pretty desperate considering I was only 16 and held back a year in math and science. But I said, sure. So I fired up the ol’ Compaq Presario, wrote his name at the top in huge red letters.

Thinking back on it now, it probably looked like a ransom note for a kidnapped clown. But I put it on a floppy disk, walked 15 minutes up the hill to Kinkos and printed it out on this thick, blue paper so it would stand out from the rest of the resumes. I was very proud.

But when I showed it to my dad, he was like...

“Qué es esto? What the hell is this? It’s like you don’t want me to get a good job. You want me to fail.”

I’d spent hours on that resume! So I grabbed it, stuffed it down the back of my pants, literally wiped my ass with it, and threw back at his face. And then I pushed him. He pushed me back. And then he said “I have a gun.” And that was the end of it.

My dad didn’t ask me for help again.

Instead he took things into his own hands. On job applications, he changed his last name from Garcia to Gassiot. Thought it made him sound more European, but that didn’t work because he was all like, “Oh, you want to know where I am from? Paris, France. I grew up on the steps of the Champs d’Elysees!”

He also enrolled in more adult ESL classes.

Only the classes took place at my high school. During the day, across from my home room. While I was there.

Yeah, me and my dad went to high school together. He used to drive us both to school. And I’d have him drop me off a block away and pretend I didn’t know him. Man, I was a dick.

My dad ended up going back to Rockwell doing part-time contract work. Eventually, Rockwell’s defense and aerospace division was sold to Boeing, and he worked there, too. But the country’s golden age of defense spending had passed, and work was slow. My dad got restless.

So he got a second job in a warehouse, packing DVDs. I remember finding copies of “Clear and Present Danger” around the house. He’d lift them from work and sell them to his friends at the barbershop. I don't think of it as stealing. I just think he knew how to optimize his income.

My mom says that by the late 90s, my dad started acting off. A little lost. But at the time, she didn’t tell me.

There's only one Cuban I know of who’s ever been to outer space. His name is Arnaldo Tamayo Méndez.

I’ve seen videos of him on YouTube, and at one point I even tried to get an interview with him for the podcast. But I got a ‘not gonna happen’ from the Cuban government.

Still, I've been thinking about him lately. He and my dad were the same age, and they both grew up poor in Cuba. But their lives went in such different directions.

Chris: Tamayo became a revolutionary. He fought for the communists in Vietnam, and in 1980, was part of a Cuban-Soviet space mission which spent seven days in space. Tamayo became a national hero.

My dad didn’t live a celebrated life. But he raised two kids in a country where he had no roots. We never went hungry. We got college educations. One of us became a missionary and a teacher. The other was privileged enough to live his childhood dream and become a stand-up comedian.

These are the lives that our father provided for us -- filled with the kind of opportunities he never got to experience for himself.

Since I lost my dad, I like to go back to the places he used to love. Even the California Science Center.

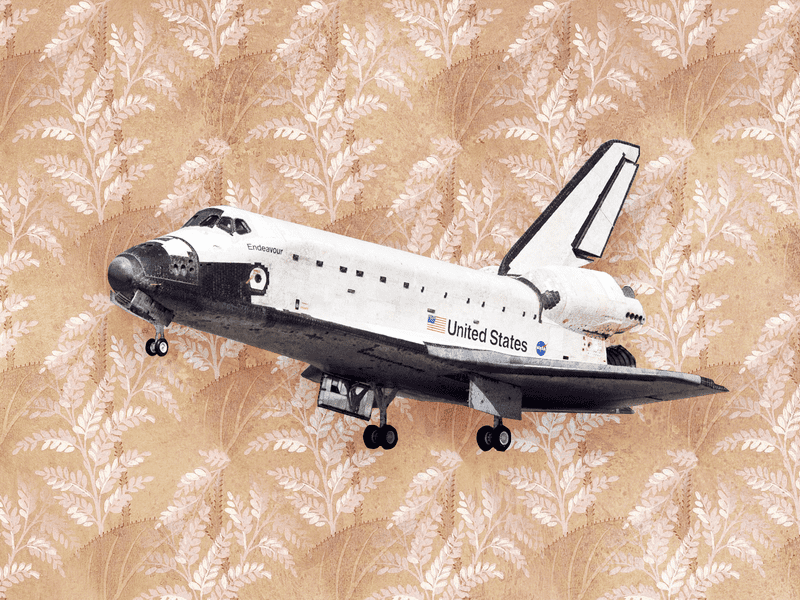

They don’t have the same Robotic McNuggets anymore, but they have something better: the Space Shuttle Endeavour.

“T-10… Booster ignition and liftoff of the maiden voyage of Endeavour on a satellite rescue mission…”

Chris: The Endeavour is sort of the Michael Jordan of the American space program. It’s the greatest of all time.

When you picture a spaceship, you’re probably picturing The Endeavor.

It flew 25 missions, starting in 1992. It orbited the earth more than 4,000 times. It went to the International Space Station, and helped fix the Hubble Telescope. I think my dad would be pretty amazed that I know all that.

It was finally retired in 2011.

“Thank you, Houston. On behalf of my entire crew… I want to thank every person that worked on Endeavour…”

Chris: And when they were bringing it to the museum, they hauled it through LA on the back of a massive truck. People lined the streets.

*CHEERING.* “USA! USA!”

Chris: Now it lives at this museum. It looks like an airplane and Shamu at the same time.

Standing around the exhibit are a handful of docents -- guys who look like they’re in their late 60s, early 70s, wearing name tags and buttons that say, “Ask me about the Endeavour.”

If my dad were still alive, he’d definitely be one of these guys.

Eddie: How are you doing sir?

Chris: Good, I was just talking to Harvey and he said that a lot of the volunteers and docents here used to work in the space program and stuff. Did you work -

Eddie: Yes, I worked at NASA almost 30 years.

Chris: This is Eddie Fry.

Eddie: I am 74 years old. You know, getting there. I'm still healthy. I, I raise parrots. I got 16 birds at home… And yeah, and I got dogs, I got fish tanks, you know, my grandkids come over, they -- they're either looking at the birds or they’re playing with the dog or the little ones are in the fish tank saying whoa, you know.

Chris: I love this guy.

Eddie: So that’s all good, y’know.

Chris: My, uh, my dad worked um for Rockwell. In the 80s he worked for Rockwell International and then, uh, later Rocketdyne I think when it, when it -

Eddie: Rocketdyne’s the engine builders.

Chris: The engine builders.

Eddie: Yeah.

Chris: But he was a general machinist.

Eddie: So if your dad worked at Rockwell in the 80s, there’s something in the Endeavor that he probably put together. Believe me. The panels all back up and here are all machine parts here you got your rudders. Those are, they've got different angles and it’d have to be machined.

Chris: Wait wait wait. Eddie is saying that my dad, Andres Primitivo Garcia, most likely built something that went to outer space? And not just something -- the Endeavor?

Eddie: So yeah, it was, if he was there at Rockwell, cause Rockwell was the owner of all this. You know, they they were the ones who were responsible for the space shuttle program.

Chris: So yeah, inside I’m going to pieces. But I try to play it cool with Eddie.

Eddie: It was good talking to you.

Chris: Thank you Eddie. Take care. Thanks for your service to everything.

Eddie: You’ve got, your dad’s got stuff in here. He has to, he was at Rockwell. Okay.

Chris: Great, thank you.

Eddie: Alright, have a good one now. Alright, bye.

Chris: No idea. No idea these types of contributions that my dad really had to the space program and this particular shuttle. Ah. No, what he said that I was like, I’m gonna leave now. I was like, yeah, this is probably a later thing. And he's like, oh no, this was completed in 19, from 87 to 91. Exactly when your dad would have been there, you know, no idea. That's wild.

Do they have astronaut ice cream here? Hold on. Ah, the line’s too long.

“It feels like I’m being part of history… I’m seeing history in the making…”

“It’s absolutely incredible… the amount of human knowledge that goes into this thing”

“It isn’t perfect… it is rough and beat up. And you can tell, it’s been somewhere, many times.”

“It’s a once in a lifetime chance and I’m glad to see it happen”

“One last victory lap for NASA… A glimpse of history.”

“A first-class endeavor, that will help the shuttle fit in as the newest star in Tinseltown”