Part 1: The Viability Line

Julia Longoria: A heads up, this episode starts with a story of pregnancy loss.

Julia Longoria: I'm Julia Longoria. This is More Perfect.

Gabrielle Berbey: How old were you when you got pregnant for the first time?

Julia Longoria: Today’s episode comes from producer Gabrielle Berbey.

Margot: I was 30, uh, I was 34.

Gabrielle Berbey: And it starts with a woman named Margot. She’s never set foot in the Supreme Court. But in 2014, when Roe v. Wade was still law, her first pregnancy made her confront a line the Court drew. That story began when she was about nine weeks pregnant.

Margot: So at nine weeks, uh, was when I started writing weekly letters to my baby.

Gabrielle Berbey: What kind of stuff would you write?

Margot: I think I talked about snapdragons and how you can make 'em open like mouths. And so how excited I was to, you know, like show her how to do that. How when you squeeze the sides of snapdragons’ mouths , you can make 'em talk. I kept up the weekly letters until I ran out of pages in that journal.

Gabrielle Berbey: Then at 18 weeks the trouble began.

Margot: One of the ventricles in her brain was measuring on the high side of the normal range.

Gabrielle Berbey: The scan showed that something was wrong with her baby’s brain development. So doctors asked her to come back in a few weeks for a follow-up scan.

Margot: By 22 weeks it was in the severe range and there were other abnormalities. When somebody brought up abortion, that made it clear to me that what was going on was real bad. I mean, every one of them knew that I wanted that baby.

Gabrielle Berbey:They knew there was a chance her baby had a rare congenital brain disease, but it was too early for a diagnosis and they didn’t know how severe it would be.

Margot: The big thing that we were waiting for at that point, was the information that the MRI could give us about the brain development a month down the line.

Gabrielle Berbey: In one month, scans could tell her a lot more about her baby’s quality of life.

Margot: Either the complications were so great that she would die before she was born, or immediately after birth, or never leave a hospital kind of stuff, and they just couldn’t say at that point.

Gabrielle Berbey: But the problem was — in a month, it would be too late.

Margot: I was told that if I wanted an abortion I needed to decide right then. And I didn't have enough information.

Gabrielle Berbey: She was 22 weeks pregnant then. In just two weeks — at the 24 week mark — it would be too late to have an abortion because of a line the Supreme Court drew in 1973 in Roe v. Wade. The viability line. That’s the point in a pregnancy when a baby could theoretically survive outside the womb.

Biologically, it's a fuzzy line. It’s impossible for doctors to declare the viability of any pregnancy with certainty. In Roe v. Wade though, “viability” was the cutoff. Before the line, abortion was legal. After the line, it was up to states to legalize it or ban it.

Margot lived in Michigan, where abortion is banned after "viability," and her hospital wouldn't perform an abortion after 24 weeks.

Margot: You're telling me that if in two weeks you tell me that my baby has a fatal disease, you can't help me?

Gabrielle Berbey: She couldn’t possibly make a decision about having an abortion in that moment.

Margot: I knew I just didn't have enough information. Being so afraid of not being able to get an abortion later that you have an abortion even not know — oh, God. No.

Gabrielle Berbey: But the thought of making her baby suffer down the line was also unbearable.

Margot: There's obviously no medical reason for that, right? All of the reasons for that happening are legal and they're not sense-making legality, right? This is nonsense legality! Because nobody thinks that this is a good scenario. So how did we end up here? What has been missed?

[Archive Clip, Justice John Roberts]: We will hear argument this morning in case nineteen thirteen ninety two. Dobbs versus Jackson Women's Health Organization …

Julia Longoria: In the oral argument for Dobbs — the case that overturned Roe — the word abortion came up 73 times. The word precedent 24 times. Privacy 10. But viability?

[Archive Clip, Scott Stewart]: We asked the Court to at least get rid of a viability line or any suggestion of a viability line.

[Archive Clip, Justice John Roberts]: Viability, it seems to me, doesn't ...

[Archive Clip, Elizabeth Prelogar]: ... before viability.

[Archive Clip, Scott Stewart]: Viability?

[Archive Clip, Justice Sonia Sotomayor]: That basic viability line.

Julia Longoria: 111 times.

[Archive Clip, Justice Samuel Alito]: The line really doesn't make any sense

[Archive Clip, Scott Stewart]: Viability is not tethered to anything in the Constitution

[Archive Clip, Elizabeth Prelogar]: Viability is a principled line, your Honor, because in ordering the interests of ...

Julia Longoria: The viability line was the line that protected the Constitutional right to most abortions for 50 years. But in Dobbs …

[Archive Clip, Justice Sonia Sotomayor]: You want us to reject that line of viability and adopt something different.

Julia Longoria: … the line was thrown out.

However you might feel about abortion, there’s no question Dobbs has thrown abortion law in America into a state of chaos. State laws are changing across the country at a breakneck speed.

Politicians are deciding where they’ll draw their own lines at any point in the pregnancy: Arizona, 15 weeks; Georgia, six weeks; in 14 other states, conception.

[OYEZ THEME: Oyez. Oyez. Oyez.]

Julia Longoria: Today on More Perfect, the story of the very first line — the viability line. How it went on to transform everything, from who can have an abortion, to the way doctors practice medicine, even to the way we understand pregnancy. It’s a line that’s so embedded itself in our culture, not even the Supreme Court can erase it.

[OYEZ THEME: God save the United States and this Honorable Court. Oyez. Oyez. Oyez.]

Julia Longoria: This is More Perfect, I’m Julia Longoria. Reporter Gabrielle Berbey set out to trace the origin of the viability line in Roe v. Wade. The decision in that case was written by a justice named Harry Blackmun.

Gabrielle Berbey: But my question was where did Justice Blackmun get the idea for the viability line? First I pulled up on the opinion online — ctrl+f — viability. To see if he explained why he chose that line. He didn’t.

Julia Longoria: That would have made for a short episode.

Gabrielle Berbey: Yeah, wrap it up.

Julia Longoria: Where did you go next?

Gabrielle Berbey: So then I had to go deeper. And luckily, shortly before Justice Blackmun died, he gave his papers over to the Library of Congress. So I went there. And there were 1,576 boxes of papers that Justice Blackmun donated. So I was sifting through all these boxes. And found stuff like a box of mostly hate mail that Justice Blackmun kept after the Roe v. Wade decision, letters to friends. The volume of stuff was totally overwhelming until I found a clue.

Gabrielle Berbey: You had two files in Justice Blackmun's clerk box. Were you particularly close?

George Frampton: Well, you know, yes, I was close to him because of the abortion case, really. I mean, it's foxhole camaraderie,

Gabrielle Berbey: It turns out Justice Blackmun spent many, many hours in the foxhole writing Roe v. Wade with one clerk.

George Frampton: George Frampton, I clerked for Justice Blackmun in the Supreme Court.

Gabrielle Berbey: George was a clerk who stayed on an extra summer after his clerkship to help draft Roe v. Wade. But he was quick to tell me, he was not Blackmun’s teacher’s pet. When he first got the job, he didn’t even want to work for Justice Blackmun.

George Frampton: I was thinking, how can I go to work for a newly minted Nixon conservative justice?

Gabrielle Berbey: In fact, when he first visited the Court as a law student he was not impressed.

George Frampton: It sort of looked like a second-rate train station. I mean, really old white guys who didn't seem to be paying any attention to much. I was horrified.

Gabrielle Berbey: But as a lawyer fresh out of law school with an offer from a Supreme Court justice, you just don’t turn that down.

Gabrielle Berbey: What exactly do clerks do?

George Frampton: Well, a big part of a law clerk's job is the equivalent of cleaning out the stables every morning so the horses can run.

Gabrielle Berbey: The horses being the justices. Clerks do the research judges need to make their decisions.

George Frampton: Here's the case. Here are the facts, here's the law, here's some questions to ask.

Gabrielle Berbey: And George says on off hours they also sometimes hang out with their justices.

George Frampton: You know, every once in a while, Justice White played basketball with the law clerks. And he always cheated. He was mean. He would hit you with his elbow. He was a dirty player, you know. That was not Blackmun.

Gabrielle Berbey: Blackmun was softer. And George found that despite all his skepticism for the Court, he liked his boss.

George Frampton: He was so informal. He would have breakfast almost every morning with the clerks in the cafeteria.

Gabrielle Berbey: Blackmun would order the same thing every day — a scrambled egg and raisin toast.

George Frampton: Most people were tourists or, you know, came to the cafeteria and had no idea one of the justices was sitting down there with a bunch of young lawyers. He was a very down to earth, modest person who cared much more about what the law's impact was on ordinary people than he did on legal theology or legal ideology. And I think, you know, came to the Court with a lot of anxiety about whether he was going to be up to it.

Gabrielle Berbey: When it came time to pick which justice would write the controversial opinion of Roe v. Wade, the chief justice at the time chose Justice Blackmun. Now, we don’t know exactly why, but it’s not hard to imagine some reasons:

Blackmun knew something about medicine. He’d previously served as the legal counsel for the Mayo Clinic in his home state of Minnesota. And he was a centrist. Even though he was appointed by Nixon, he wasn’t a Nixon yes man. He was a diplomat — who could write an opinion that the most number of Justices split on this issue — would sign onto.

During summer recess of 1972, Blackmun holed up in the Mayo Clinic Library poring over books about the history of abortion. But he wasn’t on his own.

George Frampton: So I was in Washington.

Gabrielle Berbey: He had the help of his clerk, George.

George Frampton: And I was looking at facts and he was referring me to things too to look at. We did talk on the telephone maybe once every week or 10 days.

Gabrielle Berbey: Justice Blackmun took his first crack at an opinion.

George Frampton: The opinion he circulated was pretty thin. He didn't really resolve the issue of the extent to which abortion was a Constitutionally protected choice. It sort of flirted with that idea, but didn't come right out and say it. And so he commissioned me to write something that would do that.

Gabrielle Berbey: So it was George’s turn to give it a shot. He was tasked with finding the strongest Constitutional case for some right to an abortion. And the way he saw it there were two competing rights at play.

George Frampton: The courts were never going to say that unborn fetus from the time of conception is a person who has full Constitutional rights. That's not something that our judicial system is ever gonna recognize. On the other hand, we can't let a woman decide at eight and a half months to end a pregnancy and terminate the potential life of her fetus child. That's a little too much to contemplate. You're going to have to find a compromise in the middle someplace. That's just inevitable.

Gabrielle Berbey: Now: the idea that people would get an abortion on a whim at eight and a half months is just not true in a practical sense. It does not happen. It’s a misconception that pops up especially in politicized conversations about abortion.

But for better or for worse, at the time he was drafting Roe, George was thinking about pregnancy and abortion in more theoretical, legal terms — trying to balance the interests of two parties. He wrote Justice Blackmun with a suggested edit, and that was the note that I found at the Library of Congress in George's clerk box.

George Frampton: It's been a long time since I've seen this.

Gabrielle Berbey: George hadn't seen this note since he wrote it over 50 years ago.

George Frampton: It really is like seeing your, you know, self come back alive.

Gabrielle Berbey: I'm wondering if you can read that part just out loud.

George Frampton: I have written essentially a limitation of the right, depending on the time during pregnancy when the abortion is proposed to be performed. I've chosen the point of viability for this turning point when state interests become competing for several reasons …

Gabrielle Berbey: George said to Blackmun, how about we use the point in the middle of a pregnancy called viability as the line where the state’s interest outweighs that of the pregnant person, and states can ban abortion after that point.

George Frampton: That's part of my sales pitch.

Gabrielle Berbey: Did Justice Blackmun get viability from your proposal in that memo?

George Frampton: I assume so.

Gabrielle Berbey: Where did you get the term viability?

George Frampton: Well, it was very much part of the medical literature and, I think, part of the legal background.

Gabrielle Berbey: It was hard to chase down that legal background. From what I could tell, there was nothing published about viability in abortion law when George was writing his letters. But at around the same time, there was one other judge holed up in his chambers looking at viability in a different abortion case in the lower courts.

George Frampton: Not sure that case has been decided, I would be very happy if it were before this.

Gabrielle Berbey: Why would you be happy?

George Frampton: Well, because at least I'm not making it up.

Gabrielle Berbey: Actually can you just start with introducing yourself and saying who you are and what you do?

Judge Jon Newman: My name is Jon Newman. I'm a senior judge of the Second Circuit Court of Appeals.

Gabrielle Berbey: Judge Newman introduced viability into abortion law in a lower court. But his opinion came out a few months after George wrote about viability in his private letters to Blackmun.

Judge Jon Newman: The case came to me in 1972, just two months after I had been appointed.

Gabrielle Berbey: When an abortion case landed on his desk, a year before the Roe decision, he, like Blackmun, was a bit of a centrist — the swing vote on the Second Circuit.

Judge Jon Newman: The appellate judge thought it was a fairly clear case and the state could not regulate abortions at all.

Gabrielle Berbey: But the second judge …

Judge Jon Newman: He took the view that the state could ban all abortions.

Gabrielle Berbey: Which left Judge Newman the tiebreaker.

Judge Jon Newman: I was the third judge and I didn’t accept either absolute view.

Gabrielle Berbey: Judge Newman was wrestling with the same question as George. Both of them felt if they were going to make abortion legal, it can't be all or nothing.

Judge Jon Newman: We've gotta pick a line. And so I suggested a line of viability as the dividing line. If the fetus could not become a human being outside the womb, it seemed to me the state interest did not outweigh the private interest of the woman. And I just thought, you can't abolish her right. But you can limit it. And so where to limit it was then the issue, and the viability line seemed to me the sensible line.

Gabrielle Berbey: Why did it make sense to you at that time?

Judge Jon Newman: You have to use some judgment. There's no magic to it. People use judgment in their daily lives all the time. I don't know that anybody knows exactly why they decided anything. Who to marry, what college to go to, what job to take. Any of those big life decisions.

Gabrielle Berbey: Did you talk to doctors or OBGYNs in trying to figure out what made sense?

Judge Jon Newman: No. Um, when, when any judge decides a case, you decide it based on the record. You don't go out and talk to other people, even experts.

Julia Longoria: So these judges are drawing medical lines in the sand and they’re not even required to consult a doctor?

Gabrielle Berbey: Well, this isn’t trial court, so they're not hearing from experts on a stand like you see in “Law & Order.” But we do know that Judge Newman did have an affidavit from a doctor that referenced the viability line.

[PHONE RINGING]

Dr. Virgina Stuermer: Hello?

Alyssa Edes: Hi, is Virginia there?

Gabrielle Berbey: Producer Alyssa Edes tracked down the only doctor Judge Newman cited in his opinion.

Dr. Virgina Stuermer: This is she.

Gabrielle Berbey: Dr. Virgina Stuermer. She’s 99, so she’s no longer practicing.

Alyssa Edes: Hi, Virginia. My name is Alyssa Edes. I'm calling from WNYC, the public radio station in New York.

Gabrielle Berbey: She had the TV on when Alyssa called.

Dr. Virgina Stuermer: I truly don't wanna listen to a pitch, but I will send a check.

Julia Longoria: [laughs]

Gabrielle Berbey: It was a cold call.

Julia Longoria: Oh my god.

Alyssa Edes: I'm trying to figure out where the concept of viability came from.

Dr. Virgina Stuermer: Well, that came from — oh yeah, I don't know where that came from.

Gabrielle Berbey: All Judge Newman cited from Dr. Stuermer’s affidavit was about where viability is in a pregnancy. Not how it should be applied to the law. She did tell us though, personally, she wouldn’t feel comfortable performing an abortion after 20 weeks.

Dr. Virgina Stuermer: But that's not any scientific thing.

Gabrielle Berbey: I spoke to doctors and a medical sociologist to understand how the viability line is used in medical practice. Around 23 weeks is the point at which the lungs of a fetus may be developed enough that a baby born could breathe — with a ton of help. But that’s not the only factor doctors use to determine if a fetus is viable. There’s no such thing as a viability test. In fact, it’s not uncommon for two doctors to disagree about whether a fetus is viable.

So Justice Blackmun took this fuzzy medical concept from the realm of prenatal care and turned it into a legal cut-off to define abortion care.

Doctors have pushed back — hard — saying that the line is telling them how to practice medicine, and that it ignores scientific evidence. For this reason, The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists actually opposes abortion legislation or regulation that uses viability as its standard.

And the justices themselves have also had their doubts. Sandra Day O’Connor — the first woman on the Court — worried that using the viability line put the justices, quote, “in the business of being in a science review board.”

Judge Jon Newman: I disagree with that.

Gabrielle Berbey: Judge Newman, again.

Judge Jon Newman: We will be doing what judges do in all cases, and assessing the competing scientific views that are presented to us and deciding which one we think is more persuasive. We have to do that in patent cases, copyright cases, environmental cases all the time. So there's nothing special about doing that in an abortion case. The fact that doctors can't opine with certainty whether at a certain point the fetus is or is not viable doesn't distress me at all. No line is gonna yield perfect results. No legal doctrine is gonna lead or even entirely consistent results. The law is imperfect just as life is. That doesn't bother me. And I would rather accept a few imperfections than be forced into all or nothing decisions.

Gabrielle Berbey: Judge Newman repeated this again and again in our conversation — judges have to pick lines. That’s what judges do.

George Frampton: Viability, as a measure of when you can say that potential life becomes more life-like, more real life. It seems to me, you can say, well, that's the grossest, clumsiest reading. But it's also pretty simple.

Gabrielle Berbey: George, Blackmun’s clerk, he agrees.

George Frampton: At some point, if you think that the state has an interest in preventing a woman from having an abortion at nine months, and you also think that life is not fully protected at conception, then you have to pick a point.

Gabrielle Berbey: And the justices deciding Roe v. Wade were also searching for a point. Justice Blackmun actually didn’t take up George’s proposal for viability at first. Blackmun agreed the state had an interest in protecting fetal life at some point in a pregnancy, but thought the 12-week point was more convincing. So he drew the line there, at the first trimester. He wrote to the other justices, and said, quote, “This is arbitrary, but perhaps any other selected point, such as quickening or viability, is equally arbitrary.”

Justice Powell pointed to Judge Newman’s opinion which had just come out and said: I’d go with viability. Then Douglas comes back, and says: first trimester is better. Marshall steps in and is like: absolutely not. Another vote for viability. And Brennan is like: viability is okay with me, so long as we’re clear about the reasoning here — this is not about the woman, it’s about the state’s interest in protecting fetal life. And Blackmun never stops having his doubts, but what seems to draw him back to the viability line is this: could this arbitrary point be good enough to command a court? In other words, is this the best compromise for these nine men?

[Archive Clip, CBS News]: Good evening, in a landmark ruling the Supreme Court today legalized abortions.

Gabrielle Berbey: And ultimately, it was. Roe v. Wade was a 7-2 opinion. It read, quote, “a person may choose to have an abortion until a fetus becomes viable.”

[Archive Clip, CBS News]: The Court's decision, written by Justice Blackmun, thus sets limits on the right to abortion on demand. One limit is the time when doctors believe the fetus may be able to survive outside the mother's womb.

Gabrielle Berbey: This was a real win for abortion rights. But as soon as the decision came down, something else happened.

Alex Harris: The goal was always to overturn Roe v. Wade. The viability line is a very easy target

Julia Longoria: After the break, leaders in the anti-abortion movement converge with their sights set on Roe’s weakest link.

Julia Longoria: From WNYC Studios, this is More Perfect. I’m Julia Longoria.

[Archive Clip, Elizabeth Prelogar]: Viability is a principled line, your Honor, because in ordering …

[Archive Clip, Justice Samuel Alito]: Well, I'm trying to see whether it is a principled line …

Julia Longoria: Viability — a line in a pregnancy drawn by a clerk and couple of judges in the ’70s — was at the center of Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization. Mississippi tried to pass a ban on abortions before viability, which would violate Roe. But Justice Samuel Alito pointed out viability isn’t some magical line where the pregnant person’s right to choose stops, or the interest in protecting a fetal life begins. Don’t those things exist at every moment in the pregnancy?

[Archive Clip, Justice Samuel Alito]: You agree with me at least on that point, that a woman still has the same interest in terminating her pregnancy after the viability line has been crossed.

[Archive Clip, Elizabeth Prelogar]: Yes, your Honor. But the Court balanced the interest and in ordering the …

[Archive Clip, Justice Samuel Alito]: Then look at the interest on the other side. The fetus has an interest in having a life. And that doesn't change, does it? From the point before viability to the point after viability?

Julia Longoria: In the opinion, Justice Alito wrote that, quote, “the viability line makes no sense,”and promptly destroyed it at the federal Constitutional level. He said rt was not adequately justified in Roe. And even the dissenters to Dobbs don’t try to defend it.

But for 50 years before this, the viability line lived as Constitutional law and in that time, it embedded itself in our culture. So deeply that even though viability seemed to show up out of nowhere, it came to define the entire conversation about abortion on both sides.

Gabrielle Berbey has the rest of the story.

Gabrielle Berbey: As soon as Roe v. Wade came down, the viability line came to take on a kind of moral significance.

[Archive Clip, C-Span]: The National Right of Life Committee is opposed to Roe versus Wade.

[Archive Clip, C-Span]: Is it okay for us to allow unviable infants to be left to die?

[Archive Clip, C-Span]: Viability by definition means that the child can survive outside the body of the mother, then why kill the child?

Gabrielle Berbey: On the Conservative Christian right viability was an easy target. The line as a cutoff point was condemned as immoral.

[Archive Clip, C-Span]: No matter how you define these terms, you can say fetus. You can talk about viability and medical procedure and abortion. You can talk about all these words, but it boils down to children, innocent, unborn children.

Gabrielle Berbey: They built a movement around teaching people its flaws.

Alex Harris: Around the age of 12 I read a book called “Pro-Life Answers to Pro-Choice Arguments.”

Gabrielle Berbey: Alex Harris learned about viability as a kid.

Alex Harris: So the book reads, “In Roe v. Wade the Supreme Court defined viability as the point when the unborn is quote, ‘potentially able to live outside the mother's womb.’ But why not say he becomes human in the fourth week, because that's when his heart beats, or the sixth week, because that's when he has brain waves? Both are also arbitrary, yet both would eliminate all abortions currently performed.”

Gabrielle Berbey: He’s a lawyer now, but when he was younger, Alex was sometimes referred to as a Jonas brother of the evangelical movement.

Gabrielle Berbey: I’m picturing you on a stage with, like, a headset with cool hair, pumping up a crowd of evangelical teens, is that …

Alex Harris: We did do that. We had these big foam rocket launchers that we would shoot into the crowd to give away copies of dense theological books to teenagers.

Gabrielle Berbey: His parents were pioneers in the Christian homeschool world, part of a larger movement called the Joshua Generation. The movement trained kids in debate, public speaking, political campaigning — all before they were even teenagers.

Alex Harris: And all of this was to prepare us to be senators and the U.S. Supreme Court justices and the presidents of our generation. And really, the vision was to take the land for Christ and for conservative values.

Gabrielle Berbey: Alex made it to the Supreme Court as a clerk for Justice Kennedy. He also clerked for Justice Gorsuch when he was still on the lower court. His very first gig was interning for a anti-abortion judge in Alabama who, long before Dobbs, worked to tear down viability in the lower courts.

Alex Harris: He was known for writing opinions where he would identify, you know, all the many ways that the law does confer rights and protections on a fetus to, kind of, build the argument for why the fetus should be identified and recognized as a person and why Roe is therefore wrongly decided.

Gabrielle Berbey: The goal was to protect life from the moment of conception and ban all abortions. In response to those attacks, abortion advocates and Democratic lawmakers, they ended up doubling down on viability.

[Archive Clip, Barbara Boxer]: We have laws in this land. We have court decisions in this land. Before viability, in the early stages of a pregnancy, a woman gets to decide with her family and her doctor and with her God what her options are.

[Archive Clip, Dianne Feinstein]: I believe that abortions post-viability should not take place except in the rarest of exceptions.

[Archive Clip, Barbara Boxer]: We say after the fetus is viable. No abortion, no procedure.

Gabrielle Berbey: To secure the survival of Roe, Democratic lawmakers tried to make viability stronger by attempting to write it into federal laws. They never stopped to question if it even made sense.

Khiara Bridges: After a couple of decades of people repeating viability, viability, as like this magical point in the pregnancy.

Gabrielle Berbey: Mhm.

Khiara Bridges: I think that it made sense at that point to give viability even more magic.

Gabrielle Berbey: This is Khiara Bridges.

Khiara Bridges: Professor of law at UC Berkeley School of Law.

Khiara Bridges: I think that viability has become a point that many, many, many people across a political spectrum believed to be the point at which abortion is immoral, and therefore ought to be illegal. Like, we wanna match up morality with legality.

Gabrielle Berbey: She says viability — which to be clear, was not a word in the national abortion discussion before Roe v. Wade — is now how the majority of Americans understand abortion morally.

Khiara Bridges: Even people who are, you know, supportive of abortion rights we don't subject viability to critique. Because it seems the logical point at which people can be compelled to give birth. But I mean, I think that what's obvious is, folks are left out of that, right? People who need and get abortions after viability. Young people, poor people, people surviving intimate violence. People's lives on the ground are so much messier than what the Court pretends people's lives look like.

Gabrielle Berbey: When the viability line was drawn, it didn’t change the fact that some people still seek later abortions. What it did do was make access to care even more difficult, if not impossible.

Margot: I understand why viability feels meaningful and significant and big, but when I try to pin it down, it feels quite slippery and small in comparison to the things that I really care about.

Gabrielle Berbey: This is Margot again, the woman who wrote to her unborn daughter about showing her the snapdragons.

Margot: This is from December 8th, 2014. I was 27 weeks, 4 days pregnant. And all of the letters at this part were to, dear future kid. [deep breath]

Gabrielle Berbey: She was waiting for test results that would clarify her daughter’s brain condition, and she ran out of time in her state to have an abortion because her pregnancy crossed the viability line.

Margot: [breath] At the follow-up ultrasound last Friday, they found that the ventricles in your brain have increased to 14 to 15 millimeters on the right. [shuddered breath] Which is nearly twice what’s considered normal.

Gabrielle Berbey: Margot lived in Michigan. Following Roe, Michigan allowed abortions before viability, but banned them after that line. So when Margot decided she did need to have an abortion, her doctors told her she would need to travel to a state that did allow the procedure after viability. In this case, Colorado. The clinic she went to is one of the few in the country that would do an abortion in the third trimester. She says it looked like a bunker designed to protect the staff and patients from bomb threats and shootings.

Margot: I don't know how many cases of later abortion were looked at before people decided to try to write laws that said they couldn't happen. But it seems to me like that's the sort of thing you would wanna do, um, is not come up with a theoretical, pull it out of the sky.

Gabrielle Berbey: Judges drew the viability line because, they said, they had to balance two opposing interests: it was the person’s right to choose versus the state’s interest in protecting fetal life.

Margot: For me, she was always a kind of life worth protecting. I wanted her to live.

Gabrielle Berbey: I spoke with several women who had later abortions and later abortion providers — and they all said the same thing ...

Margot: What did people think they were preventing when they wrote the law the way they did?

Gabrielle Berbey: How does this line actually function in people's lives?

Person 1: I think I always go back to, we have to look at what drives someone to have an abortion, and why is that person at 26, 27, 28 weeks desperate to have an abortion? What are the circumstances? That's the key.

Person 2: I think the only thing that the line did was make me afraid that there was a clock that was about to run out.

Gabrielle Berbey: The people who ended up on the other side of the line or even close to it, they found themselves alone.

Person 2: I didn't know where to go. I didn't feel like there was any kind help for processing that grief.

Person 3: I remember feeling that the abortion that I had, because it was later, that it was the worse abortion. That it was less justified, that it was morally less okay.

Person 1: Roe was the floor. But I never thought it was a good decision to begin with. Why did they do this? They screwed us all over.

Gabrielle Berbey: I wanted to go back to the people who drew this line in the first place, to ask them what they meant it to be.

Gabrielle Berbey: Did you see it as a moral line?

Judge Jon Newman: No. No.

Gabrielle Berbey: Judge Newman again.

Judge Jon Newman: It's not up to courts to make moral decisions in a case. We are not the clergy. I am obliged to interpret the Constitution. Whatever our views of morality is, we ought not to impose them on others.

Gabrielle Berbey: Would you do anything differently knowing what you know now?

Judge Jon Newman: Well, I, I don't look back. [laughs]

Gabrielle Berbey: Why do you laugh?

Judge Jon Newman: Judges have enough to do with the case that's on for today and the case that's coming up next week. And I don't think it's a good use of their time to go back and say, would I have done it differently 50 years ago?

George Frampton: I've never sort of felt too much of a reason to go out and defend it in the sense that …

Gabrielle Berbey: George Frampton, Blackmun’s clerk.

George Frampton: …it is what it is. Was what it was. It worked. To the extent that it's become a thorn, a disadvantage in the abortion debate, I'd never thought that much about it. I guess I just thought, well, it's always been vulnerable. But as long as it's out there at least guaranteeing most people the right to an abortion.

Gabrielle Berbey: Yeah. So you still feel that viability is the one that makes the most sense?

George Frampton: No. Not today.

Gabrielle Berbey: Why not?

George Frampton: I don't have any particular pride in the brilliance of, you know, the original Roe v. Wade decision. So, I mean, I never really thought about the viability of viability. You know, there's nothing magical about viability. If you want a rule of law, you have to pick a line. If there is a point someplace in the middle and you can't use viability or quickening, and you can't use a number of months as an approximation, how do you articulate the right to build the law on? To build a whole legal and health system on? Tell me what you think it's gonna be.

Gabrielle Berbey: Abortion law was built on the assumptions of men — what they did and didn’t understand about medicine, about pregnancy, about loss. Liberals, who supported abortion rights, used that law, tried to make it stronger, and in doing so made those assumptions part of how the majority of Americans understand abortion. Conservatives focused their attention on that law to destroy it, to fight for a new legal and health system. And they won.

Gabrielle Berbey: When Dobbs was decided, did that feel like an accomplishment?

Alex Harris: You know, it really felt surreal in many ways.

Gabrielle Berbey: I went back to Alex Harris, the Jonas Brother of the movement that helped destroy the viability line in federal law.

Alex Harris: But there was not the jubilation that I think I may have felt even 10 years prior. Most of that was just my greater understanding of how this decision would impact the lives of so many women. Um, including women in my own life.

Gabrielle Berbey: Hm.

Alex Harris: The fear that I knew and had heard and saw from so many of them in response to this decision. And if my hope, and the hope of true Christians and followers of Christ, was in the Supreme Court to right all those wrongs — the brokenness of our world, the brokenness of our political system, and the brokenness of our judicial system — it’s not prepared to do that.

Gabrielle Berbey: Where do you see this going? Now that viability is gone?

Khiara Bridges: So we now don't have to defend viability. Our creativity has been unleashed.

Julia Longoria: Right now, there are people who are looking for a new standard.

Khiara Bridges: We're starting to see the proliferation of arguments for abortion rights that don't rely on the due process clause. You know, equal protection arguments. Free exercise arguments.

Julia Longoria: Next week, Part 2: the Supreme Court asked for an alternative to viability, we go to the people looking for one.

Person 4: When does life begin? It begins at the beginning.

Person 1: A pregnancy is viable if it's wanted and accepted and embraced.

Person 2: I think most people who support abortion rights actually probably think there should be a line, but what if we don’t? What if we just allow people to decide what it means to them?

Alyssa Edes: More Perfect is a production of WNYC Studios. This episode was produced by Gabrielle Berbey and me, Alyssa Edes. With editing by Jenny Lawton and Emily Siner. Fact-check by Naomi Sharpe.

Special thanks this week to Jeannie Suk Gersen, Sam Moyn, Anna Sale, Lauren Cooperman, Erika Christensen, Garin Marschall, Katrina Kimport, Benedict Landgren, Nina Martin and Glen Halva Neubauer.

Thanks also to Hillary Frank of The Longest Shortest Time – where we first heard Margot’s story. And to the Library of Congress for their help with Blackmun’s papers.

The More Perfect team also includes Julia Longria, Emily Botein, Whitney Jones and Salman Ahad Khan.

The show is sound designed by David Herman and mixed by Joe Plourde.

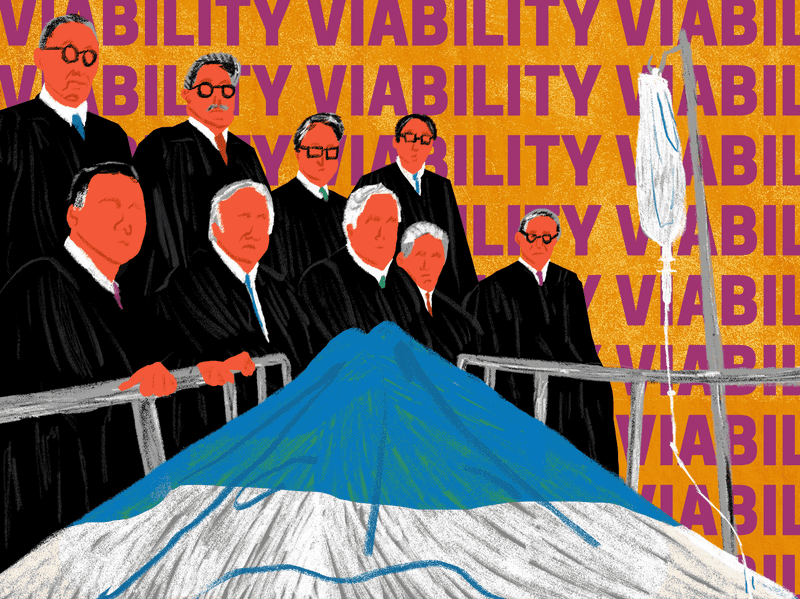

Our theme is by Alex Overington. And the episode art is by Candice Evers.

If you want more stories about the Supreme Court, go to your podcast app, hit subscribe and scroll back for more than two dozen episodes.

Supreme Court audio is from Oyez – a free law project by Justia and the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Support for More Perfect is provided by The Smart Family Fund. And by listeners like you.

Thanks for listening.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.