Your Moment of Zen

( On the Media/ WNYC )

BOB GARFIELD: This is On the Media. I’m Bob Garfield.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And I'm Brooke Gladstone. As I suggested a few minutes ago, apes don’t deserve nice things. We have to evolve fast to earn our democratic system. This week, in The New Republic, Rebecca Solnit recalls a Zen story she heard a long time ago, a samurai who demands that a sage explain heaven and hell to him. The sage replies by asking why he should explain anything to an idiot like the samurai. The latter becomes so enraged in response that he draws his sword and prepares to kill. The sage says, as the blade approaches, that’s hell.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

The samurai pauses and realization begins to flood in; the sage says, that’s heaven.

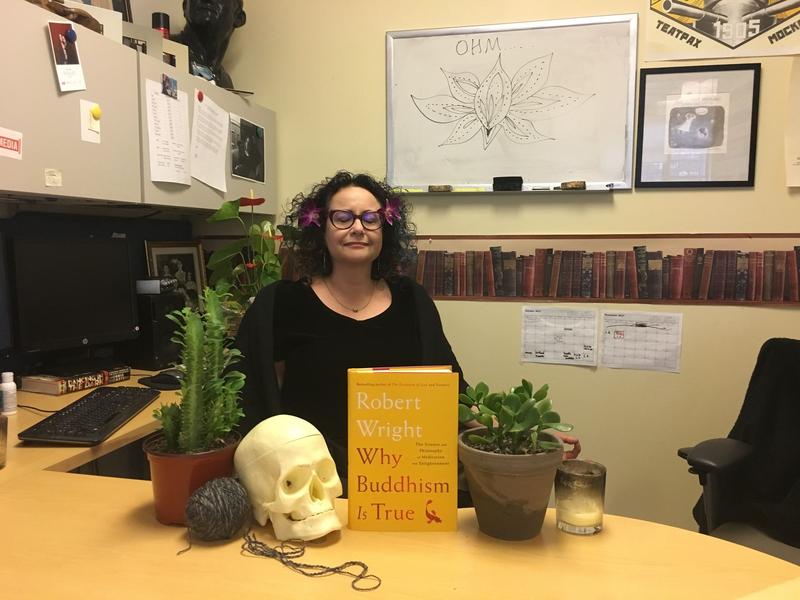

But how do you get there from here? How do we short circuit the wiring that leads to embracing bad information that supports our views and the reflexive dismissal of the character and motives of those not within our own tribe? Bob Wright, author of Why Buddhism Is True: The Science and Philosophy of Meditation and Enlightenment, told us last year that before we can get our minds moving in a healthier direction, we have to know where they’ve been.

ROBERT WRIGHT: Brains were designed by natural selection to do one thing, get genes into the next generation in a particular environment, in something more like a hunter-gatherer environment. And that's when I see crazy things like road rage that don’t seem to make any sense. I mean, rage made a little more sense in a different environment.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Explain.

ROBERT WRIGHT: Well, in a hunter-gatherer environment, rage gets you to demonstrate that you cannot be taken advantage of. Somebody tries to steal a possession, a mate, whatever, you show you’re willing to fight. You get mad enough to fight. Even if you lose the fight, you’ve demonstrated that there's a cost, okay? Well, you take this out on the highway, well, first of all, nobody who’s watching is – are you ever gonna see again, there’s no point in demonstrating anything to them. Plus, now you’re going 80 miles an hour and the consequences could be worse. And, you know, the same with a lot of things, anxiety, guilt. A lot of things kind of misfire in the modern environment.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Give me an example of how guilt misfires.

ROBERT WRIGHT: You might feel you did something to somebody. You wonder, did I offend them, and you feel a little guilty but they're not like living right next door to you. You won’t see them around the campfire that night. And, and that kind of thing can fester for a long time and just go unresolved. You know, it’s not quite worth emailing them about and you're left there wondering. That just didn't happen in the natural environment. Everyone you interacted with, you interacted with pretty much all the time.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So what you've got is a, an accumulation of, like, a haystack full of little twigs that you carry around like a weight that are meaningless and that don't matter.

ROBERT WRIGHT: Yeah, well one of the take homes of Buddhism is that you should not assume that your feelings have the meaning they seem to have. You know, when they tell you this person is a bad person or you should be upset about this, don't assume that they're giving you good guidance.

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

And, and mindfulness meditation is, to a large extent, a way of looking at your feelings from a more objective standpoint. It doesn’t mean you don’t have feelings. You experience them but you exert more conscious control over which feelings you let carry you away and carry your train of thought away.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: You are not the first person I would assume would take a plunge into Buddhism. You seem to be far more engaged in examining faith than in embracing it.

ROBERT WRIGHT: It’s true that I’m not a natural meditator. It doesn't come easily to me. I don't have a good attention span, and so on.

[BOTH SPEAK AT ONCE]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Me either. Do you have ADD?

ROBERT WRIGHT: Yeah.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Me too.

ROBERT WRIGHT: I, I mean, to get into meditation at all, I had to go to a silent meditation retreat. Not everyone does, but that’s what it took for somebody like me. But as for the fact that I’m analytical, as you said, I mean, mindfulness meditation is more analytical than people appreciate, in the sense that it’s a way of learning to kind of step back and analyze the feelings and, and thoughts inside your head, at least a way of viewing them with a kind of a calm objectivity.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: I have an idea for spellbinding radio right now.

ROBERT WRIGHT: I’m ready.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: [LAUGHING] Show me how to meditate.

ROBERT WRIGHT: Show you how to meditate. First of all, I don’t have a license.

[BROOKE LAUGHING]

No one should do anything I say, from here on in. But what they typically say is, you know –

[BELL SOUND]

-- close your eyes, assume a relaxed posture. Pay attention to your breath. Maybe pick a point, like, where it's entering your nose and exiting your nose. Some people pay attention to the rising and falling of the abdomen. But pick something to pay attention to. And then, you know, just watch it. [PAUSE] And your mind is gonna wander. Don't get mad at yourself or beat yourself up. When you notice that your mind is wandering, that's a small kind of victory, so, if anything, congratulate yourself. And then you'll get back to the breath.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Okay, your brain is calm. You’ve done the breathing for –-

ROBERT WRIGHT: Mm-hmm.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: -- two hours or something, and once you've gotten good at that, no matter how many days it takes you, then you start concentrating on the sound of a bird outside the window or what?

ROBERT WRIGHT: You could. I would say what's most relevant to this question of tribalism is focusing on your feelings and look at how you’re reacting to things.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: What feeling?

ROBERT WRIGHT: I remember I was at a retreat once and there was this guy who started snoring. He was falling asleep. And this really annoyed me. I’m like, I'm trying to meditate. And then I remembered, oh wait, you’re supposed to just be aware of your reaction. And the thing about a meditation retreat is you can get so, I, I guess you might say, good this at this, at least [LAUGHS] temporarily several days into a retreat, that once you see a feeling, like my kind of wrath for that person, I literally see it and I focus on it in a way that just dissolves it in the moment. Now, that –

BROOKE GLADSTONE: You mean, like as a big gray ball of –-

[OVERLAPPING VOICES]

ROBERT WRIGHT: Yeah, well, you see where in your body –-

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm.

ROBERT WRIGHT: I mean, feelings reside somewhere in your body. If you are feeling sad and you sit down and just examine the sadness, which is a good shortcut, by the way. Skip the breath. Just wait until you have a feeling, like sadness, and, and sit down, close your eyes and so – and say, well, what does sadness feel like? And you, you’ll probably notice it tends to be something that’s up around your eyes and, and maybe elsewhere. But just the very act of observation, you’re no longer thinking the sad thoughts that the sadness would make you think. Instead, you’re just looking at the sadness. And that, in itself, is a measure of liberation.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: You had mentioned that mindfulness helps you combat our natural tribalism because that’s an emotional thing and you can identify it and then you can manage it better. And a, a big part of that is confirmation bias, which is our tendency to accept and retain information that supports our views and reject or ignore information that doesn't, because in the final analysis confirmation bias has nothing to do with thinking and everything to do with feeling.

ROBERT WRIGHT: Right. You know, confirmation bias is what drives fake news on both sides. You know, I think we’ve all done this thing of either sharing something on Facebook or retweeting something that turned out to be misleading or untrue, and we shared it without actually examining it. And if you ask yourself why did you share it or retweet it, the answer is ‘cause it felt good. And, and that's the kind of feeling that you will become more aware of if you do mindfulness meditation.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: There’s another kind of bias that you talk about in the book that maybe holds treatment for our poisonous politics.

ROBERT WRIGHT: Yeah, there's a really fascinating cognitive bias that I think has not gotten enough attention, and it's a form of what's called attribution error. In everyday life, you might be standing at a checkout counter, the person in front of you is rude to the clerk and you think, that's a rude person. So you're attributing the rudeness to the kind of person they are when, you know, for all you know they just found out that their spouse has cancer or something. You just don't know why they're behaving that way.

And it turns out that how we do the attribution depends on whether somebody is in our tribe or outside of our tribe. So if it's somebody in our tribe and they do something good, we say, well, yeah, that’s the kind of person they are, they’re a good person. If they do something bad, then we explain it away and attribute it to circumstance. You know, they were under peer group pressure, whatever, whereas people in the enemy tribe, if they do something bad, you say, yeah, naturally they did this thing. If they do something good, you explain it away as being due to circumstance. And I think this kind of thing, it gets us into wars and it does help sustain the tribal conflict, and what it –

[BOTH SPEAK/OVERLAP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: But even more so, once you’ve got this explanation, you have no need to seek another.

ROBERT WRIGHT: Right.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So basically, this kind of attribution bias is a really big impediment to breaching the walls between tribes and increasing our understanding.

ROBERT WRIGHT: It, it impedes understanding. There are two kinds of empathy. People would imagine that the whole point of mindfulness meditation is to give you empathy in the traditional feel-their-pain sense, you know, in other words, emotional empathy: I feel sorry for the people on the other side. There's also something called cognitive empathy, which is just understanding what it's like to be them and why they do the things they do. And mindfulness meditation can help you, regardless of whether you even care about them, regardless of whether you feel their pain. It can help you get a clearer view of why they did the things they did. A calmer, more deliberate approach is the beginning of calming things down.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: I also think getting exorcised over the trivial invites fatigue and makes you less likely to sustain effective political action.

ROBERT WRIGHT: Right. Part of this is like a mental health issue. I mean, I just know a lot of people who spend a lot of time on Facebook or Twitter and they wind up feeling [LAUGHS] horrible because they are so outraged. And I'm not advocating that you use meditation as some kind of insulation from what's going on. You could use meditation as a sedative. That's not what I'm recommending. I'm recommending using it to clarify your vision. And the term I use is “mindful resistance.” I'm putting out a weekly newsletter now called “The Mindful Resistance Newsletter.” And it’s an attempt to help people focus on things that are really important and process every day's news in a way that is conducive to their own mental health and conducive to their own effective action.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Bob, thank you very much.

ROBERT WRIGHT: Well, thank you, Brooke.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Bob Wright is the author of, Why Buddhism Is True: The Science and Philosophy of Meditation and Enlightenment.

[”WHEN I GET LOW I GET HIGH”/MUSIC UP & UNDER]

My fur coat's sold

Oh, Lord ain't it cold

But I'm not gonna holler

'Cause I still got a dollar

And when I get low

Wo-oh, I get high

My man walked out

Now uou know that ain't right

Well, he better watch out

If I meet him tonight

'Cause when I get low

Ho-ho-ho, I get high…

BOB GARFIELD: That's it for this week’s show. On the Media is produced by Alana Casanova-Burgess, Micah Loewinger, Leah Feder and Jon Hanrahan. We had more help from Asthaa Chaturvedi, and Samantha Maldonado, and our show was edited -- by Brooke. Our technical director is Jennifer Munson. Our engineers this week were Sam Bair and Josh Hahn.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Katya Rogers is our executive producer. Jim Schachter is WNYC’s vice-president for news. Bassist composer Ben Allison wrote our theme. I’d also like to thank Tony Phillips for his wonderful John Adams. On the Media is a production of WNYC Studios. I’m Brooke Gladstone.

BOB GARFIELD: And I’m Bob Garfield.