Bob: From WNYC in New York this is On the Media, I’m Bob Garfield.

Brooke: And I’m Brooke Gladstone. John Kiriakou, a 14-year CIA veteran, left prison last week to serve the last three months of his two and a half year sentence under house arrest. He says he landed in the clink because in a 2007 ABC News interview, he had acknowledged the CIA’s use of waterboarding, which the agency had not officially confirmed. But at that time, even though he had no firsthand knowledge of the practice, he said it worked on a captive named Zubaydah and he wasn’t exactly condemning it.

Anchor: Would you call it torture?...

Kiriakou: At the time, no. [...] These guys hate us more than they love life. [...] And at the time, I thought that waterboarding was something that I thought we needed to do, and as time has passed [...] I think I’ve changed my mind.

Anchor: And with Zubaydah [the victim] you think that was successful?

Kirakou: It was.

Anchor: And bottom line as you sit here now: do you think that was it worth it?

Kirkaou: Yes.

Brooke: Now, the government says it wasn’t the waterboarding comments that put Kiriakou behind bars. It was his disclosure in 2008 of a covert CIA operative’s name to a reportery. But as he said later, he didn’t see it that way. As far as he’s concerned, he got jailed for whistleblowing.

News anchor: You consider yourself a whistleblower, correct?

Kiriakou: I do now, I didn’t in the beginning. But I’ve come to learn that most whistleblowers don’t believe they're whistleblowers in the beginning. I do meet the legal definition of whistleblowing, and that is someone who brings to light evidence of waste, fraud, abuse or illegality, and that is what I did.”

Brooke: Since we’ve lately been marinating in whistleblowers, we decided to dig in on that word. Ben Zimmer, executive editor of Vocabulary.com and language columnist for the Wall Street Journal says it dates back to the beginning of the 20th century.

Zimmer: And the original "whistleblowers," naturally enough, were people who actually blew whistles! So that would be like...a referee, in football or boxing, who might blow the whistle in order to stop the proceedings. And then it just got extended in American slang--"blowing the whistle" just meant put a stop to things. So, for example in a story that appeared in the San Francisco Chronicle in 1909 there's a slangy use of this expression: "Ah, say, Sadie--blow the whistle on that, can't you? Says I." So in that sense "blow the whistle on that" just means "just stop talking, just shut up."

Brooke: Funny, that blowing the whistle once meant to shut up. But in the 1930’s it took on a darker hue. It meant to snitch, to rat, to squeal.

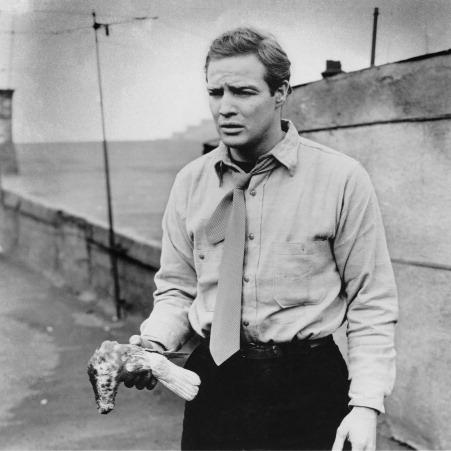

Zimmer: So we see it in various groups--the labor unions, is one example--to be called a whistleblower in the context of labor unions again becomes the equivalent of being a rat or a fink. We think about dramatic depictions of this, like On the Waterfront.

Man: You ratted on us, Terry!

Brando: I was rattin’ on myself all them years and I didn't even know it. And I’m glad what I done to you! You hear that?!? I’m glad what I done!

Brooke: And its not as if words like '"rat" have vanished in our more enlightened era. Similar epithets were applied to Edward Snowden...

DAILY SHOW MONTAGE

Brooke: What words do other nations use?

Tom Devine: The Dutch use the term "bell ringer", the people climb the church towers to warn the town of danger.

Brooke: Tom Devine is the legal director for the Government Accountability project, which offers legal aid to whistleblowers. .

Devine: The Russians use the term "lighthouse keeper," after those who shine lights on the rocks that otherwise would sink ships. The Zulus, in Africa, they call them the lookouts. They nickname them the "sentries." The Serbians ,their word for whistleblowers is "alarm raiser." But what I kind of noticed is that it is the freedom to warn that's been captured in the term as its used in many other countries.

Brooke: And so it is in America, which is why the term, is now one of honor, always applied to those...leakers...whose values we share. But when and how did a term once synonymous with "stool pidgeon" take on the mantle of moral rectitude? Well, language maven Ben Zimmer says it happened in 1970 in Washington. But the more pertinent question is: who did it? And to that he answers: Ralph Nader.

Zimmer: He wants to encourage whistleblowing in corporations, in government, in situations where there may be potentially damaging information where there could be great pressure not to reveal that information.

Brooke: So when he moves up to Washington in 1970, he starts giving speeches asking whistleblowers to step up.

Zimmer: And then the following year, he's involved in organizing the Conference on Professional Responsibility. And he said at this conference, "The whistleblower is not liked. We have invidious terms for him. He is a fink, or a stool pigeon, a squealer or an informer, or he rats on his employer." But Nader successfully rehabilitates whistleblower as a term that it's okay to be one. In a way it was really about branding, you could say. It became your civic duty, it became an ethical thing to do.

Brooke: Nader's timing was good, too.

Zimmer: This is the era the Pentagon papers, and then a bit later the Watergate investigations. And so, this was very much in the mind of people that this kind of stepping forward could be seen as something positive when the government itself was very often seen as corrupt.

Brooke: Somehow you wouldn’t think of Ralph Nader, legendary consumer advocate, erstwhile Presidential aspirant, as being into word rehabilitation. But you’d be wrong.

Nader: Well, when I got to Washington I had read a few books on semantics, and one of them had a chapter called "The Word is the Thing". [Laughs] The only way you could make a word look good is to attach it to a good deed.

Brooke: Ralph Nader.

Nader: A lot of our successes were traced back to conscientious employees who jeopardized their job and their pension and spoke out on behalf of the public's right to know and the public health and safety. You recognize that's a huge asset in our country, to have conscientious employees who will not get along by going along but will stand tall and speak out, even at the jeopardy of their own job and future income.

BROOKE: And you said, "We don't have an untainted word to describe these people"?

NADER: No, there wasn't. I got early the idea that the press liked the word "whistleblower." It was compressed with meaning. And we gave it a meaning of moral courage. We tried to make that whistleblower heroic!

Brooke: But nothing elevates a word like legal recognition. Laws that protect federal employees, like the Whistleblower Protection Enhancement Act, which Nader championed and Tom Devine of the Government Accountability Project spent more than a decade pushing through.

Devine: The Whistleblower Protection Enhancement Act has been in existence for a little over two years. It's had a very positive impact on the agencies that interpret the law.

Brooke: How so?

Devine: The loopholes have been closed that made the act irrelevant for almost everyone. And now people are getting their hearings and winning their fair share of the hearings because all the ways that the deck had been stacked were cancelled. Congress took those cards out and put fair ones in.

Brooke: The term whistleblower, as defined in the act, is not just a moral mantle, its a legal one. Devine says that since the law has passed, his group hasn’t lost a case. Now it’s defending John Kiriakou. Whatever Kirakou’s initial motivation may have been, according to Devine, now he is a whistleblower. Meanwhile, Nader is more interested in retiring words than rehabilitating them: exchange "white collar crime", for instance, for "corporate crime"; "private sector" for "corporate sector"; "settlements" for "colonies".

Nader: Oh! This is my favorite. Listen to this: The people who gouge you in the drug industry and the health industry are called providers. (Laughter) Right? I mean just think of the tremendous image elevation when you can be part of a trillion dollar industry and you're given an image of philanthropy! Here's one for you: Tort Reform. This is restricting your rights if you're wrongfully injured from having your full day in court. And they call it "Tort Reform". How about this one: the only ethnic group that now is slandered with impunity. You'll never guess. "He welshed on me!" OK. Here's another one… (fade out)

Brooke: The book that inspired Nader is called the The Tyranny of Words by Stuart Chase. He made me write it down. The lesson here: Don’t be ruled by the words institutions stamp on things. If they don’t portray the the truth as you see it, than do what Nader does. Rat them out. I mean,...blow the whistle on them.