Why the #MeToo Comeback Essays Come Up Short

( Leah Feder / WNYC )

BOB GARFIELD: This is On the Media. I’m Bob Garfield.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And I'm Brooke Gladstone. We've entered a new phase in the #MeToo era, what seems to be a comeback tour.

MALE CORRESPONDENT: The comedian Louis C.K. is facing backlash for returning to the stage.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: The disgraced comedian, found to have non-consensually masturbated in front of multiple female comics, did a surprise set at New York's Comedy Cellar last month, with mixed reactions. Indeed, the dust of the #MeToo era has not yet settled but accused offenders peer out from exile, calculating whether it’s safe to reemerge. Take former CBC host Jian Ghomeshi, way back in 2014, he lost his job as host of the popular interview show Q. after an expose in the Toronto Star.

[CLIPS]:

MALE CORRESPONDENT: At least eight women have now come forward alleging physical abuse by former CBC broadcaster Jian Ghomeshi.

WOMAN: He immediately threw me up against the wall. He started kissing me. He led me upstairs. He told me to get on my knees and then he proceeded to start hitting me hard across the side of my head.

WOMAN: Out of nowhere he grabbed my head, pulled my hair, threw me in front of him and started hitting me close-fist on the side of my head.

[END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Last week, Ghomeshi published a nearly 3500- word piece in the New York Review of Books called “Reflections from a Hashtag.”

[CLIP]

MALE CORRESPONDENT: Jian Ghomeshi discusses his life as a figure despised by the public in his own account of what sent his career spiraling downward.

[END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Ghomeshi describes the pain of his fall from grace, while obscuring the reasons he fell in the first place. The backlash was swift. New York Review of Books editor Ian Buruma who, in an interview with Slate’s Isaac Chotiner, gave a tone-deaf defense of the piece, left his job after advertisers and some writers fell away. But Ghomeshi’s apologia wasn't the first of its kind.

FEMALE CORRESPONDENT: Just days before the Ghomeshi essay came out in the New York Review of Books, Harper's Magazine published a similar essay by former US Public Radio host John Hockenberry.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: In a recent article, Slate columnist Laura Miller takes issue with both essays, beginning with what she calls Ghomeshi’s frustrating exercise in bland soul-searching misdirection and hand waving.

LAURA MILLER: The whole point of a personal essay is to really get to a deeper level of self-knowledge to really look at yourself, and yet, he makes it sound like something any guy who had success might wind up doing [LAUGHS], might wind up slapping or punching some woman while he’s having sex with her without asking her first. He makes it sound like it's just a sort of routine misbehavior and glides over the surface of how hard it is for him to have lost the status that he once had.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: He doesn't offer details. He just says some of the charges are inaccurate. He makes it very clear that this is all an outgrowth of having become a celebrity and a sense of entitlement that he knew he didn't deserve but it's been reported that some incidents date back to his days as a university student.

LAURA MILLER: Yeah, and I think anyone can identify with the success goes-to-your-head-and-you-act-like-a-jerk scenario. And that's not really what he was accused of and he doesn't really make clear what it was that he did that he regrets. The essay is not really an attempt to come to terms with the accusations and what they mean. My counterexample of a really great apology was one made by the television show runner Dan Harmon in his podcast.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: He was the show runner of the TV program Community, also a co-creator of Rick and Morty.

LAURA MILLER: And he developed a crush on one of the women writers on his show and he behaved really badly towards her. And when he made his apology onstage in front of a bunch of people and recorded for posterity, he acknowledged what he did and, most importantly, its effect on her.

[CLIP]

DAN HARMON: I broke up with my girlfriend, then I went full-steam into creepin’ on my employee and, and said, oh, I, I – I love you, and, and she said the same thing she’d been saying the entire time, please, don't you understand that focusing on me like this, liking me like this, preferring me like this, I can't say no to it and when you do it, it makes me unable to know whether I'm good at my job. It was, therefore, rejected. I was humiliated. Now I -- wanted to teach her a lesson. If she didn't like being liked in that way then, oh boy, she should get over herself. After all, if you’re just going to be a writer then this is how “just writers” get treated. When she tweets about it, you know, and refers to trauma that's -- probably because I drank, I took pills, I crushed on her and resented her for not reciprocating it, and the entire time I was the one writing her paychecks and in control of whether she stayed or went and whether she felt good about herself or not. I just treated her cruelly, pointedly, things that I would never, ever, ever have done if she had been male.

[END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: She listened because she was expecting an apology but what she didn't expect was the release.

LAURA MILLER: Yes because when you're the target of sexual harassment, it can feel unreal. So for her to have him acknowledge the reality of her experience was incredibly powerful. He was admitting that her perception of what was going on was true.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: You said, instead of the usual mealy-mouthed pro forma regrets, his apology writhes with self-loathing.

LAURA MILLER: There is this way that Harmon looks at what he does and is disgusted by it that somehow brings a clarity to the motives behind that behavior. You know, why is someone a bully? It's because they fear their own weakness.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Now, your Slate colleague Isaac Chotiner interviewed the New York Review of Books editor Ian Buruma to understand why he decided to publish Jian Ghomeshi’s essay. He said, all I know is that in a court of law he was acquitted. The exact nature of his behavior, how much consent was involved, I have no idea, nor is it really my concern. My concern is what happened to somebody who hasn’t been found guilty in any criminal sense but perhaps deserves social opprobrium. How long that should last, what form it should take, you know, that's the questions that he wanted to pursue.

LAURA MILLER: Yes, he was not convicted of any crime and also he is not in jail for any crime. People don’t want to work with him because he has a very suspicious record of being accused of sexual harassment by multiple people.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Now let’s move to John Hockenberry and his article in Harper’s. Hockenberry was the host of a show called The Takeaway, produced here at WNYC. His contract was not renewed and it was later that these complaints against him were investigated.

**NOTE** WNYC objects to this characterization of events in the previous sentence and provided the following statement:

"WNYC investigated and took action on every allegation we were aware of when John Hockenberry was host of The Takeaway. In June 2017, WNYC and PRI, co-producers of The Takeaway, did not renew his contract. When additional allegations were brought to our attention after he left, those were investigated as well."

You say that his article is of a different flavor from Ghomeshi’s. You describe it as “a windy exercise in radioactive self-pity.”

LAURA MILLER: The Ghomeshi essay is slick and calculating. The Hockenberry essay is anguished and flailing. He can't really talk about what he did without veering into this weird sociological realm that seems completely irrelevant to, you know, him propositioning junior coworkers. [LAUGHS]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: His piece begins with the image of his Emmy and Peabody Awards wrapped in plastic and languishing in a cluttered storage unit.

LAURA MILLER: It’s a random grab bag of memories and self-justification, and I just feel like a responsible editor should not have published it, as much for his sake as for the fact that it is just all over the place. And there's a long bid about Andrea Dworkin, the late feminist theorist.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm.

LAURA MILLER: It is somewhat humorous to imagine how Andrea Dworkin [LAUGHS] would have responded to being utilized in this way by John Hockenberry, to sort of prove his feminist credentials. But, again, we don't have any evidence that he has put himself in the place of the women who were the target of his behavior or made any effort to understand what effect his behavior had on them in a long-term basis.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Harper’s publisher and president Rick MacArthur, when asked about the decision to publish Hockenberry's 7,000-word essay on the CBC, here it is.

RICK MacARTHUR: Mr. Hockenberry is in a wheelchair, so that does inform the piece immensely. It's a complicated mix of atonement, regret and an attempt to explore sexual relations between men and women in the modern age. He quotes Andrea Dworkin, a noted feminist author who’s not around anymore to talk, unfortunately. He talks about the novel Lolita, if a novel like that was published would that be banned by #MeToo? These are all issues which make it rise to the level of a serious essay by a thoughtful person who, yes, has been driven out of his job, yeah.

HOST ANNA MARIA TREMONTI: He’s a paraplegic. What does that have to do with the fact that he was accused of sexual harassment? Does that excuse him?

[BOTH SPEAK/OVERLAP]

RICK MacARTHUR: It’s hard to get out of your, it’s hard to get out of your wheelchair [LAUGHS] and attack somebody.

ANNA MARIA TREMONTI: You can be sitting down, whether you’re in a wheelchair or not, and tell a woman all sorts of things that are sexual harassment, so what –

[BOTH SPEAK/OVERLAP]

RICK MacARTHUR: Sure, sure.

ANNA MARIA TREMONTI: Again, what’s your point?

RICK MacARTHUR: My point is, is that there’s a distance between a criminal act, and he’s not been accused of anything criminal, Hockenberry. He’s been erased.

[END CLIP]

LAURA MILLER: All they see when they look at these stories is a man who lost his position in the world. Again, it’s a failure of the imagination or of sympathy that they think that the harm of this guy losing his job is so much more significant than the harm of a woman who was punched or made to feel completely uncomfortable in the workplace because her boss kept coming on to her.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: I don't think they understand that at the beginning of your professional life being taken seriously is more important than anything. And if you think you're reduced to an object because you're a young woman and that you never were taken seriously, it was all a joke, I've seen it happen to people.

LAURA MILLER: Yeah.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: I’ve seen how deeply and enduringly depressed they become.

LAURA MILLER: And I honestly don't know if Buruma or MacArthur are looking back at their lives thinking, what if this happened to me? I have no idea what they are like in the workplace. Maybe they are confusing behavior that's not beyond the pale because, again, they don't really understand the details of what these men did and they also don't really understand its effect on women.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: In The New Yorker, Jia Tolentino called this genre of personal essay “My Year of Being Held Responsible for My Own Behavior.”

LAURA MILLER: [LAUGHS] I love that.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And that’s how Ghomeshi’s piece reads, with lines like, “There has, indeed, been enough humiliation for a lifetime. I'm constantly competing with a villainous version of myself online. This is the power of a contemporary mass shaming.”

LAURA MILLER: There's nothing particularly online about his disgrace. [LAUGHS] I mean, he was written about in a newspaper.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm.

LAURA MILLER: And he was dismissed from a job in broadcasting. And he sort of tries to align himself with anyone who feels that social media is sometimes unfair. By implication, if you agree that online shaming gets out of control sometimes, then somehow you're sliding towards agreeing that he has been shamed too much.

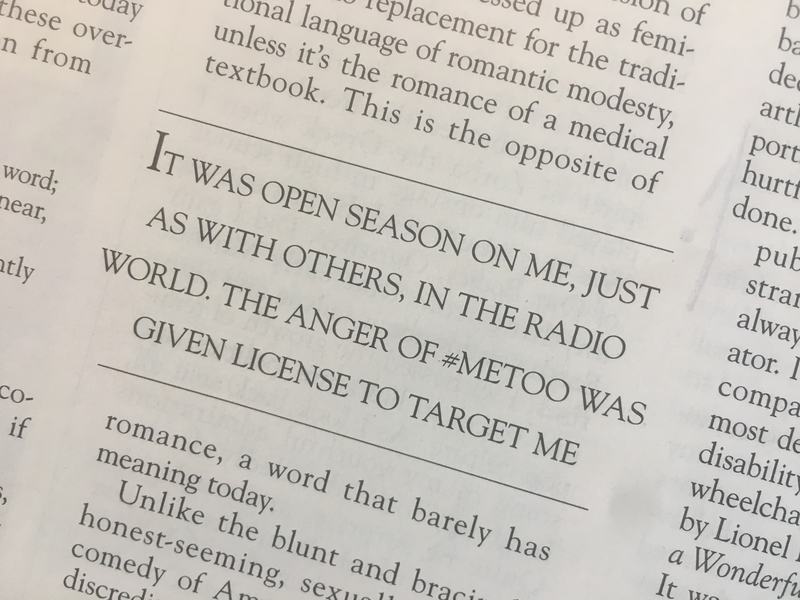

BROOKE GLADSTONE: One thing that both Ghomeshi and Hockenberry did was spend time with what you called “the aspects of their identity that makes them targets of discrimination.” Hockenberry's paraplegic and brought it up numerous times in describing how his own sexual apparatus works or doesn't. Ghomeshi is of Iranian dissent. He quotes one really horribly nasty email from someone.

LAURA MILLER: Yeah, and in Ghomeshi’s case, again, very calculated, because he is quite conversant with the lingo of contemporary wokeness and believes that he can get people on his side by talking about being a person of color or discrimination against him because he is of Middle Eastern origin. And Hockenberry, I think, wants to present himself as a representative and a champion of disabled people. I think he would also like to suggest that he's not that much of a physical threat, even though typically the power behind sexual harassment is not physical strength; it's institutional power. What they're both asking for in this essay is that we feel sorry for them. And it would be easier to feel sorry for them, as Michelle Goldberg put it in her excellent op-ed for the New York Times, if there was any sense that they felt sorry for the women that they harassed or assaulted, in Ghomeshi’s case. That’s like step number one. [LAUGHS] If there is a 12-step program for getting through the experience of being an accused sexual harasser in the age of #MeToo, number one is to actually feel some compassion.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Laura, thank you very much.

LAURA MILLER: You’re welcome. Thank you.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Laura Miller is a books and culture columnist for Slate.