What Science Says about the Birth of the Universe

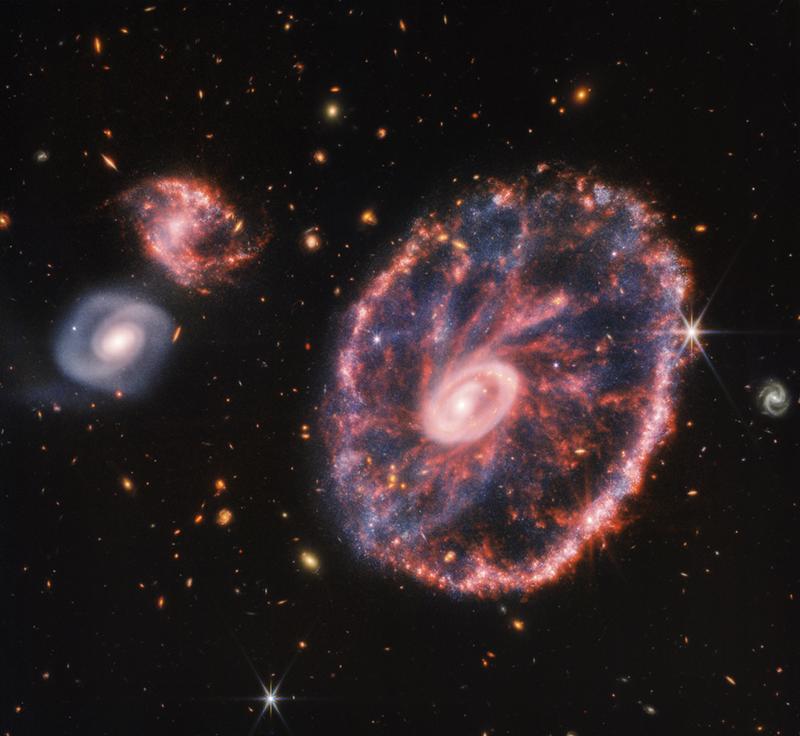

( NASA / AP Photo )

BROOKE GLADSTONE This is On the Media. I'm Brooke Gladstone, one of the brightest news stories of 2022 – maybe the past few eons – came in the form of some breathtaking images.

NEWS CLIP Today, science has made the distance between all of us and the cosmos just a little bit shorter, with perhaps one of the greatest scientific achievements in our lifetime.

NEWS CLIP A new era in astronomy. NASA's releasing a full batch of images and data from the massive James Webb Space Telescope.

BROOKE GLADSTONE The pictures show the universe as it looked soon after the Big Bang more than 13 billion years ago. The Webb Telescope is giving us baby pictures of the cosmos. In December, the telescope also offered the very first glimpse of rare galaxies beyond us as they looked at the dawn of cosmic time. Last summer, I spoke to Guido Tonelli, a particle physicist, visiting scientist at CERN and the author of the book Genesis: The Story of How Everything Began. He has long probed with mind-blowing success the origins of everything and seems to also have a grasp on how it all ends. But first, he wants us to understand how vital origin stories are, no matter where or when they come from.

GUIDO TONELLI I think is a primordial issue. If you take a look to all tribes, all small populations that sometimes have been found in the Borneo or the Amazonas, they all have a tale of the origin. It looks like we need desperately to locate ourself inside a tale, and once we have located ourselves inside the tale, then we can start organizing our societies.

BROOKE GLADSTONE It serves, you believe, as the origin of art, science, philosophy, religion.

GUIDO TONELLI Because you locate yourself in a long tradition. And the group that owns a tale of the origin is a group which has culture, which is stronger.

BROOKE GLADSTONE And you touch on a multitude of creation stories prominently Hesiod's Theogony, the best existing notion of what we think the Greeks in the seventh century B.C. might have thought about these matters. And he begins with a deity called Chaos, a word that had a very different meaning then. Hesiod's chaos was not chaotic. She was a void, and that's kind of how your universe begins, right?

GUIDO TONELLI For me, as a modern scientist that believes that the entire universe is a transformation of the void. The void resonates with the old Greek word of chaos. So it's like closing a circle that was opened by Hesiod and closed today by modern science.

BROOKE GLADSTONE In your world, collecting information on the birth of space time, how did you feel about the images coming from the James Webb telescope?

GUIDO TONELLI It's something difficult to describe because we know what is happening in the darkest side of our universe, because we have indirect evidence. But the power of an image is incredibly strong. It's amazing to see galaxies in collisions or to discover that even in the smallest and darkest portion of our universe, you can collect signs of hundreds, thousands of galaxies, each one containing hundreds or thousands of stars around which we know that we'd be orbiting an immense number of planets. We are really a very tiny object in an incredibly large structure, which is absolutely fantastic.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Do you think that they'll enable you to attack some of the mysteries that we still have, like dark energy, dark matter? You've said that it's embarrassing for scientists to know only four or five percent of matter.

GUIDO TONELLI Yeah. I'm a bit embarrassed in admitting that our ignorance is still immense. In particular, there are two major questions. One is the dark matter, which is very important because it keeps together everything- particularly the galaxies. Dark matter is everywhere, including in this room, and we are not able to explain what it is. And dark matter accounts for something like 27–28% of the entire universe. Even worse is dark energy. Two-thirds of the universe is made out of this strange form of energy, which makes everything expand at an increasing speed. The real hope that we have today is that the James Webb telescope will give some light in some of these mysteries.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Do you think it's possible we’ll ever get a glimpse of the big bang?

GUIDO TONELLI Ha, ha. This is a very good question. We cannot go to the Big Bang because there is a limit, and the limit is a sort of a wall. And the wall is the moment in which the radiation, which is light, most of the telescope uses a sort of light or some frequency — light separated from matter only 380,000 years after the Big Bang. So we have reached already this point and we can see the baby universe. Unfortunately, we cannot go beyond this with electromagnetic radiation. But today we have understood how to use gravitational waves. So if we are able to improve the sensitivity of the gravitational wave detectors, then we might be able to really see life the very first instant of the birth of our universe.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Wow. You direct your vision to the astoundingly large and to the unimaginably small, the infinitesimal particles that make up everything. Do these two kinds of data work together to piece together our origin story?

GUIDO TONELLI So science uses basically two independent teams of pioneers. The teams of astrophysicists or astronomists looking at objects which are very far away. They see them back in time. We, the other team, the particle physicists, study the tiniest possible object, the elementary particle. We bring back to life particles that were extinct since billions of years. Our universe at the very beginning was extremely dense and extremely hot, very different from the the large and cold and dark universe we have today. In the expansion, the universe has become cooler and cooler. That means that these particles are not able anymore to leave. The temperature is too low.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Mm hmm.

GUIDO TONELLI But in the particle accelerator, the Large Hadron Collider at CERN, for example, producing collisions between protons, as we do, the density of energy reaches a value which is similar to the value of the original universe. This is why in this tiny portion, going high in energy, in temperature means going back in time.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Ten years ago this month, after decades of building intricate instruments to probe the cosmic mysteries, you had an astounding breakthrough at the Large Hadron Collider near Geneva. You and your colleagues announced the discovery of the almost mythical Higgs boson, known popularly as the God particle, because of its role in giving mass to all the other particles, basically creating everything.

GUIDO TONELLI This hunt for this elusive particle occupied the lifetime of that generation of scientists. The previous generation, without success, they were not able to discover it. Now we know why. Because it is a particle which is extremely heavy. And the machines that were produced in the 60 or 70’s, they were not able to produce it. For a scientist like me, being aware that you are among the first humans to look at a new state of matter that was not available since the beginning of the universe, since billions of years, is something which is difficult to describe.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Is there any way to briefly explain the significance of the Higgs boson and how it contributes to our creation story?

GUIDO TONELLI Imagine that for a moment. We can fly there and see the baby universe — sort of a fog of elementary particles, each one indistinguishable from the others. This universe could have expanded forever without forming nothing interesting — would have been a perfect universe, but completely useless without the possibility to create the stars and galaxies, flowers, human beings, rocks, etc.. And this is why it is so important. Because after 100th of a billionth of a second, this tiny moment just after the Big Bang is the moment in which the universe cools down enough to allow the Higgs boson.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Higgs boson.

GUIDO TONELLI That was one of these particles flying around without any particular role. It started freezing because the universe became too cold. Now the universe is not any more perfect. Now each particle has a different mass. Now there is not the same density everywhere. There is differentiation. It is thanks to a few of these particles that we can form the first protons and around the proton you can have a lepton, which is an electron flying around. So you can have the first atom, you can form the first clouds of dust of hydrogen that will give birth to the first stars that will give birth to the first planet. Without this initial touch, our universe would have remained forever a perfect but useless universe.

BROOKE GLADSTONE There are creation stories. What about extinction stories? What are the best theories about the end? Many have postulated a Big Crunch, basically an expanding universe, changing direction, smashing into itself.

GUIDO TONELLI The Big Crunch has basically been abandoned because the evidence we have is that our universe is continuing its expansion at an increasing speed. One possibility for the fate of our universe will be that this expansion will continue forever. That means that after tens of billions of years, the universe will be too cold, everything will be too distant, and there will be no creation of new stars. It will become a very depressive universe full of black holes, neutron stars. It is called the thermal death of the universe.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Mhmm.

GUIDO TONELLI There is another possibility that is quite recent is in connection with the discovery of the Higgs boson, because the Higgs boson that is producing this mechanism, allowing particles to have mass and to aggregate any stable forms. So if the Higgs boson goes to another transformation and disappears immediately, we have collected data that hints that this could be possible. That tomorrow at 4:00 in the morning, immediately in the entire universe, the Higgs field degrades. If this happens, the entire universe will become a huge bubble of pure energy. So everything will disintegrate. There will be no possibility of adding stars of galaxies or planets or human beings etcs. We come back to the original situation, the perfect sphere of elementary particles, all massless, that are not able to aggregate in any form. It will be a hotter universe with nothing to be described.

BROOKE GLADSTONE You talked at the beginning of how important it is to the development of culture and art and the strength of societies to understand their origins. To have some story about it. I just wonder if you think contemplating our end has value in itself.

GUIDO TONELLI We thought it was impossible to damage significantly the planet. Now we have realized that these mechanisms are quite finely tuned, and if you intervene too strongly you might destroy equilibria which are there since millions of years ago. Now we know that the same is true for the entire universe. Imagine for a moment we have been in the last 2500 years speculating that we are subject to death while, the moon, the sun, the planet Earth was, eternal. Now, science tells us that there is an inner fragility in the entire universe, and so we as material beings share the same fragility. For us — is 80, 90, 120 years, for the universe is billions of years. But for me, it is absolutely amazing to discover that modern science tells us today that the fragility of the human beings is shared by the immense structure of our beautiful universe.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Thank you very much. Guido Tonelli is a particle physicist and the author of the 2021 book Genesis: The Story of How Everything Began.

Okay. So we don't have much agency when it comes to the thermal death of the universe. But Guido's point about connection was one made in some fashion by all our guests this week, and that reminded me of a conversation I once had with Michael Pollan, who wrote How to Change Your Mind. He told me he was drawn to the subject of psychedelics, in part because of some work that was being done in hospitals with terminal patients, people who were terribly afraid of what was coming. They were offered psilocybin, which suppresses the part of the brain that governs separateness from our surroundings. It gave them direct experience of a connection to everything that most of us can't achieve on our own. It opened them up to the idea that all separate things come to an end, including their pain and themselves, even as all things come together. And they were less afraid. I'm not advocating drug use here. I wish there were a pill. All we've got is a little free will making the decision not to despair.

On the Media is produced by Micah Loewinger, Eloise Blondiau, Molly Schwartz, Rebecca Clarke-Callender, Candice Wang, and Suzanne Gaber with help from Temi George. Our technical director is Jennifer Munson. Our engineers this week were Andrew Nerviano and Sam Behr. Katya Rogers is our executive producer. On the Media is a production of WNYC Studios. I'm Brooke Gladstone.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.