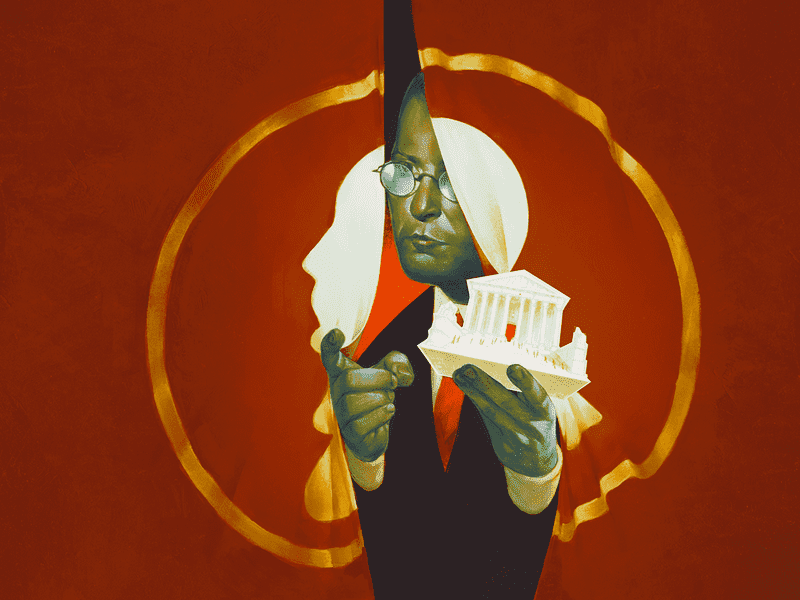

Part 1: A Bobblehead Doll of Leonard Leo

[music]

Brooke Gladstone: From WNYC in New York, this is On the Media, I'm Brooke Gladstone. We're one week into the United States Supreme Court's new term.

News Presenter 1: The justices are returning to the bench under a cloud of ethics controversies and with public opinion of the court at a historic low.

Brooke Gladstone: About that cloud, one news organization has done more than most any to expose how some members of the bench have violated ethics and rejected norms, and that organization has been our partner in the investigation you're about to hear. It's part two of our three-part collaboration with ProPublica called We Don't Talk About Leonard, an investigation into the rise of the conservative legal movement, and Leonard Leo with a secret behind its stunning success. In this hour, reporters Andrea Bernstein, Ilya Marritz, and Andy Kroll will be our guides. Last week, Andrea took us back to Leo's earliest days-

Andrea Bernstein: I'm looking for yearbooks.

Brooke Gladstone: -his high school in New Jersey.

Andrea Bernstein: Okay. I've got the '83 book. I'm opening it up.

Brooke Gladstone: We heard from a former classmate about his deep interest in the law and his convictions.

Snehal Shah: He was always passionate about being anti-abortion. He was very steadfast in that belief.

Brooke Gladstone: We learned about a college professor who was an important early influence.

Jeremy Rabkin: The law schools are overwhelmingly tilted to the left, certainly in the area of constitutional law.

Brooke Gladstone: We charted the rise of Leo's influence on the conservative movement, his decades-long association with the Federalist Society, an avid promoter of conservative legal doctrine whose mantra is "ideas have consequences."

Amanda Hollis-Brusky: More importantly, that policy is people. You have to connect those ideas to the right people who have access to the levers of power.

Brooke Gladstone: We saw how he built a network of nonprofits.

Vivica Novak: What you had was a daisy chain where donors were giving money to one group. The group didn't have to disclose its donors. They'd give money to another group. That group didn't have to disclose its donors.

Brooke Gladstone: Finally, how Leo shifted his attention from the US Supreme Court to the state Supreme Courts.

Wolff: It's not enough to own a house and own a Senate and own a governor. We got to own courts too so that-- It is a power grab. There's no question about that. That's the way you control the court.

Brooke Gladstone: Leo said as much himself.

Leonard Leo: In fact, one can very ably argue, I think, that state supreme courts are in many cases where the rubber really meets the road.

Brooke Gladstone: In this episode, Ilya, Andrea, and Andy will explain how Leo, the people as policy guy is busily constructing pipelines of well-placed legal talent in state governments too. Here's Ilya.

Ilya Marritz: Mike Black is an attorney in Montana. He got his degree from Cornell Law in the late 1980s which is where he crossed paths with Leonard Leo.

Mike Black: Leonard Leo was in my law school class. We lived in the same dorm the first year of law school.

Ilya Marritz: Black says Leonard Leo stood out. For one thing, he looked young. He was young. He got his undergraduate degree and law degree in just six years.

Mike Black: I don't even think he was old enough to drink. I don't think he was even 21 years old at the time.

Ilya Marritz: Like other classmates we've spoken with, Black remembers Leo for wearing suits to class. It was a vibe.

Mike Black: He had an agenda, he had an ideology, and he was very serious about it.

Ilya Marritz: Leo had founded the Cornell Law chapter of the Federalist Society. It was a pretty new organization then, and Black didn't see them or Leo going far. It was all this talk about the original meaning of the Constitution at the time the founders wrote it.

Mike Black: It wasn't something that I personally took very seriously, and frankly, I was clearly wrong because I should have taken it more seriously.

Ilya Marritz: After Cornell, Mike Black ended up in Montana practicing law. For nearly a quarter century, he did not think about Leonard Leo. In 2013, Mike Black is working for the Montana Attorney General as a career employee heading up the Civil Division. The AG just changed from a Democrat to a Republican, so there are a bunch of new people in the office. Black has something to discuss with one of them. He takes a walk down the hall to speak with his new colleague.

Mike Black: I went into his office, and on his bookshelf were all these bobbleheads. There was like Scalia for sure, and I think probably Alito. There were like four or five, I don't remember how many there were. Then there was this one younger-looking guy, and I said, "Well, who the heck is this?" He goes, "That's Leonard Leo."

Ilya Marritz: Black looks at his colleague, a man named Lawrence VanDyke, the Montana Solicitor General. He looks at the bobblehead doll, a miniature of someone he used to know.

Mike Black: I think I laughed, and I told Lawrence that, "I went to law school with Leonard, and I can't believe that there's a bobblehead doll of him." It was clear that Lawrence was enamored with Leonard, and considered him a friend, and ultimately I think it's been borne out that Leonard Leo was a patron of Lawrence VanDyke. At the time, I just thought it was funny.

Ilya Marritz: Leonard Leo was on that shelf of bobbleheads alongside Supreme Court Justices. It's a visible manifestation of the work he's done to shape the court. If that's all he did, he wouldn't be as influential as he is today, because the justices would only be hearing those cases that happened to get to them. Leo has done something maybe more impressive, something not many people know about. He's built a system that makes it much more likely that the right cases get to the high court, the cases he and his ideological brethren believe are most likely to nudge the law in the direction they think it should go.

He does this by taking an active interest in other parts of the legal world, lower court judges, state courts, state attorneys general, and solicitors general, people like Lawrence VanDyke, the owner of the Leonard Leo bobblehead doll.

Lawrence VanDyke: I was like, "Solicitor? That sounds like, does he wear a wig? What is that?"

Ilya Marritz: This is Lawrence VanDyke, reflecting back on the start of his career on a recent podcast.

Lawrence VanDyke: I definitely didn't know anything about solicitor generals. That was the first time I heard the term, and I thought it was a funny term at the time.

Ilya Marritz: It was new to me too, when we started this reporting. I got interested after speaking with a former Republican attorney general. This AG told me that solicitors general play a pivotal role in Leo's system. In most states, the elected attorney general chooses his or her solicitor general, and it's the solicitor who argues the state's big cases in the Supreme Court and appeals courts.

News Presenter 2: The Supreme Court struck down President Biden's plan to cancel up to $20,000 in student loan debt for millions of Americans.

News Presenter 3: Despite growing dangers from climate change, tonight the US Supreme Court curbing the government's power to fight it.

News Presenter 4: An ideologically split US Supreme Court has upheld Ohio's controversial use-it-or-lose-it voting law. It allows the state to automatically purge people from its list of registered voters if they fail to vote for two consecutive elections and fail to return a mailed postcard confirming their address.

News Presenter 5: The federal appeals court has ruled that the Biden administration likely overstepped First Amendment protections when it urged social media companies to remove misleading or false content about COVID-19 and other issues like election integrity.

News Presenter 6: The US Supreme Court has blocked President Biden's vaccine or test mandate for large private companies. Today, it essentially ruled that OSHA, the federal workplace safety agency, exceeded its authority with the mandate.

Ilya Marritz: State solicitors argued and won all of these, including the conservative legal movement's biggest victory.

News Presenter 7: Roe v. Wade is history. That landmark 1973 ruling that said a woman had a constitutional right to abortion now goes back to the states.

Ilya Marritz: These victories can be traced back to the extraordinarily effective long game played by Leonard Leo and the groups around him. It's an effort that unfolded mostly out of sight before the first briefs were filed. To really see it, you'd need to be plugged in to the Federalist Society.

Leonard Leo: We're going to have a conversation this morning about state attorneys general. This is an issue of great importance to the Federalist Society.

Ilya Marritz: This is Leonard Leo at a Federalist Society gathering in 2015 introducing a panel discussion on the role of AGs. This coincided with his ongoing push for state Supreme Court changes which we heard about in episode one.

Leonard Leo: We're seeing an unprecedented amount of activity by state AGs, particularly with regards to pushback against federal overreach that oftentimes comes in the form of litigation.

Ilya Marritz: By this point, Barack Obama is in his second term as president. Conservatives are fighting the Affordable Care Act and resisting new regulations put in place after the 2008 financial crisis.

Leonard Leo: Not only are there an unprecedented number of lawsuits being brought against the federal government by state AGs, but an unprecedented number of state AGs joining in each of those lawsuits. It's a very interesting time.

Ilya Marritz: What's really interesting is what Leonard Leo was doing behind the scenes. One, and this is classic Leonard Leo, a group he had influence over in an informal way was pouring money into a group that in turn put money into elections for State Attorneys General. In 2014, the AGs campaign group, the Republican Attorneys General Association, became a standalone group called RAGA. The first 17 contributions were each for $350. Then came a contribution for a quarter of a million dollars. It was from the Judicial Crisis Network, a group formerly known as the Judicial Confirmation Network, or JCN, a Leo-connected entity that, among other things, funnels money into campaigns.

Under a different name JCN remains RAGA's biggest and most reliable funder today. Two, he was organizing them. RAGA has a sister group dedicated to policy. The Judicial Crisis Network also funds it. They do weekly calls where solicitors share what they're doing. The calls are Thursday afternoons. There are regular retreats and seminars where these days scholars and activists talk about issues like election integrity and woke corporations. The effect of this is to draw state AGs' attention and resources into national policy issues. Their are more typical bread-and-butter focus would be consumer protection or Medicaid fraud. On that podcast, Lawrence VanDyke explained it like this.

Lawrence VanDyke: If you have the right position in state government, you'll get to sort of have this national practice.

Ilya Marritz: Lastly, there's personnel. When a Republican AG has an opening, I've been told by a former state AG, Leo has suggested the names of potential staffers pre-vetted for ideology and skills. He won't say, "Hire this person" in a bossy way. He'll say, "This is a good guy. You should check him out." One such guy was Lawrence VanDyke, owner of the Leonard Leo bobblehead doll.

Montana is a state that sometimes has a hard time attracting the most highly qualified candidates. When Lawrence VanDyke arrived, people noticed. He graduated magna cum laude from Harvard Law. He was an editor on the Harvard Law Review. On a podcast recently VanDyke said, "That put him on a path."

Lawrence VanDyke: While I was in law school it was a combination of being on law review and being very interested in religious liberties. Made me more interested in the appellate legal issues route.

Ilya Marritz: After law school, he goes to work at a big Republican-oriented law firm in Washington under the tutelage of the son of a Supreme Court Justice-

Lawrence VanDyke: I worked very heavily with Gene Scalia doing labor stuff, but mostly admin law and of course clerking on the DC circuits.

Ilya Marritz: -before becoming Assistant Solicitor General briefly in Texas. For all those qualifications, attorney Mike Black found there were things VanDyke couldn't or wouldn't do.

Mike Black: Obviously very bright, writes well, very opinionated, but he wasn't very seasoned as a lawyer. He didn't understand the nuts and bolts of what we did every day very well.

Ilya Marritz: Like establishing the facts of a case through discovery and depositions.

Mike Black: Not only did he not understand the nuts and bolts, he didn't seem particularly interested in learning what they were.

Ilya Marritz: Black says and others in the Montana AG's office told us the same, "If a case didn't line up with VanDyke's views, he didn't want to take it." One example was a Montana law that restricted political spending in state judicial races.

Mike Black: This was a hard case to defend. Don't get me wrong. We were defending a restriction on speech in an election, which is a tough road to hoe, but at least with respect to the history of Montana and the culture of our elections, it was an important case.

Ilya Marritz: Like the law or not Black thought it was VanDyke's job as solicitor to defend it. He didn't.

Mike Black: He literally refused to get involved.

Ilya Marritz: Lawrence VanDyke declined to do an interview with us and did not answer a detailed list of questions. We can tell from his emails from that time that what lit VanDyke up were cases about national issues involving religion, guns, and out-of-state litigants. For example, he recommended that Montana join a challenge to New York's restrictive gun laws passed after the Sandy Hook School massacre adding as an aside in an email, "Plus semi-automatic firearms are fun to hunt elk with as the attached picture attests smiley face."

Mike Black: He liked guns, he liked shooting guns, he liked talking about guns. He thought that concealed carry should be a right.

Ilya Marritz: While he was solicitor VanDyke served on two Federalist Society executive committees on religious freedom and separation of powers. He communicated regularly with Federalist Society officials and allied law professors. He persuaded Montana to join suits and amicus briefs that mattered to this crowd, like a contraception in healthcare case known as Hobby Lobby. It resulted in the US Supreme Court recognizing, for the first time, a private company as having religious rights.

Mike Black: I think he had aspirations clearly to do something beyond being the solicitor in Montana.

Ilya Marritz: Mike Black was older and more experienced. Lawrence VanDyke was young and bright and equal to him on the org chart. You could chalk up their friction to rivalry or a personality thing, but there was something else. They seemed to have totally diverging views on what VanDyke was there to do. Lawrence VanDyke arrived in the Montana AG's office at a time when his job, Solicitor General was dramatically changing. Paul Nolette, a political science professor at Marquette University, told me that just a decade or two ago, not that many states had solicitors. It was a dead-end job.

Paul Nolette: Something that didn't offer a whole lot of career advancement was not a way to elevate one's name in legal and political circles.

Ilya Marritz: Mainly solicitors argued cases that were being appealed through state courts. These lawsuits typically didn't attract much attention. Then State Attorneys General started to use their solicitors general differently. They could appoint and deploy them to make big moves on hot-button issues.

Paul Nolette: Even in those smaller states like Nebraska and Kansas, these offices Oklahoma amongst Republican AGs, these offices have been some of the strongest pushback against the Obama now Biden administrations. These are high-profile positions.

Ilya Marritz: These jobs don't pay anything like what you could make at a big law firm. For conservative jurists becoming SG is a form of early career credentialing that can pay off down the road.

Paul Nolette: A number of them have gone on to judgeships, have gone on to other high profile positions within the judiciary.

Sarah Isgur: Welcome to Advisory Opinions. I'm Sarah Isgur.

Ilya Marritz: They talked about this recently on the podcast Advisory Opinions. It's co-hosted by Sarah Isgur, a former Trump Justice Department spokesperson, and former Harvard Law Federalist Society chapter president.

Sarah Isgur: We've had other state SGs on the podcast, former state SGs who all just rave about it as a job. I do want-

Ilya Marritz: In April, she brought Andrew Brasher, the former solicitor General of Alabama on her show.

Sarah Isgur: For this wonderful conversation about being a state solicitor general, the tensions, the conflicts, the fun, the tears, the joy, all of it.

Ilya Marritz: Brasher gives an insider's perspective on the job and how it's changed.

Andrew Brasher: I think the Attorney General's offices have gotten more interested in national issues, national profile over the last 30 years. We're just seeing so much litigation driving public policy that anybody with a good plaintiff, which the states are in the mix to be involved in national issues and great public policy.

Ilya Marritz: States are good plaintiffs. They're more likely than private parties to have standing to bring a case. The Supreme Court is more likely to want to hear the case and if they do, the solicitor making arguments may be a familiar face. The current crop of Republican state solicitors include former clerks to Justices Scalia, Thomas, and Alito. Sarah Isgur had a front-row seat to this. Her husband was SG in Texas and a former Justice Kennedy clerk. He too had a Leonard Leo bobblehead doll. There's a photo of it in the Texas Tribune so small world.

Sarah Isgur: Let's move a little bit more to the career side then. Advice you have for people who are listening to this and are like, "Yes, me too, dude. I want to be a state SG."

Ilya Marritz: Brasher says you have to know about the job, know you want it, and be a good networker.

Andrew Brasher: The thing is, these jobs, they don't get advertised. It's not like there's just a bulletin that's like, we need a new SG in Kentucky or something. You just have to really want to do it and to know the people who are in the position to give you the job.

Ilya Marritz: Brasher went on to become a federal judge in Alabama at age 37. In an email, he told us, "I'm not aware of anything that Leonard Leo did to advance my career at any point." In response to our questions, Leonard Leo said, "Yes, he cultivated the careers of many young lawyers among them, Lawrence VanDyke." He said he doesn't remember making phone calls on VanDyke's behalf. He didn't comment on one former AG's contention that he, Leo, sometimes suggests the names of possible new hires.

Solicitors general, he told us, are often important because they're on the front lines of defending the division of power between the states and the federal government as set forth in our constitution. Leo became interested in attorneys general. He said, "Upon discovering that many of them were not focusing on their duty to defend and protect their states against unlawful and unconstitutional overreach by the federal government. Today, unlike in years past, this has become a key part of their work."

Brooke Gladstone: Coming up, Leonard Leo has very, very big plans for Lawrence Van Dyke, but first, what do an American billionaire, a Supreme Court justice, and an Alaskan salmon, have in common?

Josh Kaplan: As we're looking at this, the only common thread between the prominent guests on that trip was that they were all connected to Leonard Leo.

Brooke Gladstone: This is On The Media.