The Virtue of Mutual Contempt

( Public Domain )

BOB GARFIELD: This is On the Media. I'm Bob Garfield.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And I'm Brooke Gladstone. Amid the avalanche of Supreme Court news and the ongoing wretchedness on the border, many in the media took time out this week to address a different crisis, the impending demise of civility.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

FEMALE CORRESPONDENT: White House Press Secretary Sarah Sanders says she was out for dinner last night in Virginia when she was refused service at a restaurant because she works for the Trump administration.

SARAH SANDERS: I was asked to leave because I work for President Trump. We’re allowed to disagree but we should be able to do so freely and without fear of harm.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Cue the pearl clutchers.

GREG GUTFELD, FOX NEWS: The world’s getting hotter and it's not global warming. It's political tension driven by emotion.

MAN: No, you’re watching the left become an activist mob.

WOMAN: I would say that the polite discourse is inappropriate when there are babies in cages.

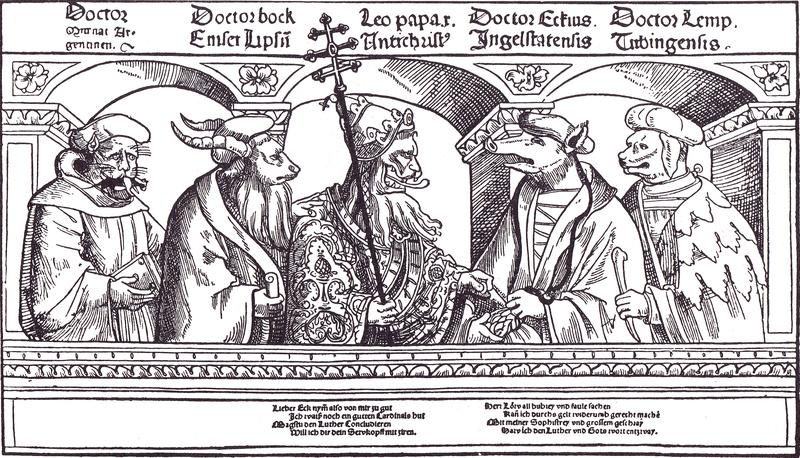

BROOKE GLADSTONE: This particular media meltdown seems to have touched a nerve, perhaps because we’ve never really settled on how best to live together. And we’ve been arguing about it for a long, long time. Consider one of history's most effective hecklers who also hounded a powerful institution. But it wasn’t the White House. It was the Vatican, just over 500 years ago.

TERESA BEJAN: He, by no means, invented uncivil disagreement but Martin Luther was a virtuoso of --

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

-- the religious insult.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Teresa Bejan is an associate professor of political theory at the University of Oxford and the author of Mere Civility: Disagreement and the Limits of Toleration.

TERESA BEJAN: You really saw uncivil speech and actually other forms of incivility as an essential part of the duty of an evangelical Christian, to put it in modern parlance, to call out [LAUGHS] the errors of others when nails or glues, you know, depending on who you ask, these 95 theological propositions to the door of a church in Wittenberg and really gets this thing that we begin to think of as of the Protestant Reformation going. A few years later, the, the Pope responds by declaring 41 of those 95 theses heretical. And Luther responds in a stroke of political genius by calling the Pope the Antichrist.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Now, that’s rude.

TERESA BEJAN: The Pope, you know, trying to take a page from Luther's book, when he finally does excommunicate Luther, he, at the same time, declares that so that Martin's followers will share in his shame they shall henceforth be denominated “Lutherans.”

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Oh, the height of rudeness!

TERESA BEJAN: Exactly. So many of the denominational labels that we know today begin in this period as really offensive and uncivil religious insults. “Puritan” starts out as an insult, someone who is overcome with purifying zeal or even Quaker, someone who’s quaking in their religious ecstasies. And, by the way, when they started out, Quakers were notorious, among other things, for taking their clothes off in public, for interrupting other people's church services by banging pots and pans. And so [LAUGHS] --

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

-- Luther’s real innovation here and I think really, really catches on and then leads to the crisis of civility that we begin to see is that it’s a duty of every individual Christian to offend those who are in errors. You have to insult them, you have to frustrate social norms of respectful behavior, so as to alert them to the depth and severity of the sin in which they’re living.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So let’s carry on with this civility debate with two of its earliest and still best-known theorists, Thomas Hobbes and John Locke.

TERESA BEJAN: So in the 17th century in England, both Hobbes and Locke are trying to figure out how it's possible for a tolerant society to exist and not dissolve into civil war. How is it possible that those who disagree fundamentally in matters of religion and in politics can nevertheless live together? Because all of the existing evidence on the ground, at least in Europe, seemed to be that that was impossible. If you wanted people to coexist peacefully, you could not have religious toleration.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So disagreement then, or the lack thereof, is a matter of -- life or death.

TERESA BEJAN: Absolutely. I mean, it's easy to sort of minimize the, the stakes of these early modern wars of religion but we have to remember that the death toll, I mean, of English civil war alone was per capita upwards of, I think, both world wars combined.

Hobbes comes to the conclusion that it's not actually religious difference that's the problem, it's disagreement that's the problem.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm.

TERESA BEJAN: So basically, you could have a society wherein people believe whatever they want, so long as they don't [LAUGHS] actually disagree about it with one another. So he comes up with this understanding of civility as what I call “civil silence.” It's basically, we can live together peacefully and un-murderously so long as we see our differences as, strictly speaking, not worth disagreeing about.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So Hobbes is, is suggesting that the people themselves could never be an engine of change because they wouldn't be allowed to argue over their ideas.

TERESA BEJAN: Yeah, Hobbes is trying to roll back that kind of empowering of the individual to call out the injustice of the status quo. And what that requires for Hobbes is a kind of absolute sovereign power to govern speech.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Whereas Locke liked argument.

TERESA BEJAN: Yeah, absolutely because argument is how we learn. He begins to think about civility really in a different way. He says, well, if we’re going to disagree productively, what are the constraints that need to be in place on how much difference a tolerant society can have? So we can only disagree within a kind of span of what we might call reasonable disagreements. So one limit is that you can't tolerate atheists because you can't have a civil disagreement with an atheist [LAUGHS], basically --

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Ohh!

TERESA BEJAN: -- is his view. But Locke is also really adamant that you can’t tolerate Catholics because they see themselves as being loyal to?

BROOKE GLADSTONE: The Pope?

TERESA BEJAN: The Pope.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So one of the main reasons why we called you is that when you approached this study of civility, you were, yourself, a civility skeptic.

TERESA BEJAN: Yeah, I saw routinely how charges of incivility were used as ways to stifle debate and that civility was very often a tool of marginalizing the marginal and suppressing dissent.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And then you discovered someone who changed your mind, Roger Williams, a radical Puritan and founder of Rhode Island. He was banished from the Massachusetts Bay colony basically for refusing to shut up. [LAUGHS]

TERESA BEJAN: That's exactly right. He’s an uncompromising Puritan English Calvinist and, on his own terms, most of the Puritans of Massachusetts Bay were not Christians at all. They were sinners. And he thinks it’s his duty to tell them that at every opportunity. He’s a really difficult intolerant Puritan.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So I assume that Rhode Island was an intolerant place.

TERESA BEJAN: That is the assumption that we would tend to make but exactly the opposite happens. When Roger Williams is banished from Massachusetts Bay and he founds the town of Providence on a gift of land from the Narragansett tribe with which he was very friendly, he opens it up for other religious dissenters who've been banished from the colonies to come and worship freely.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Why?

TERESA BEJAN: Right. [LAUGHS] I mean, Williams’ idea was that in order to have spiritual or religious purity you were going to have to have an absolute wall of separation between church and state and between civil society and religious society. So Rhode Island becomes the first society in the world not to have an established church.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So who lived there? I mean, what sort of dissenters descended on Rhode Island?

TERESA BEJAN: Rhode Island became known as a rogues’ island and the latrine of New England because [LAUGHS] just basically everyone who was too wild or uncivil to be tolerated in the other colonies found themselves there, so Catholics, Jews and then also pagans or American Indians.

But what's really exceptional here and where he goes farther than anyone else, really, and I think farther than even people like Jefferson, is that Williams thinks that not only do all of these erroneous doctrines, all these erroneous consciences have this right to live together in civil society, they all also have a right and a duty to evangelize for their errors. [LAUGHS]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Everyone has to be incredibly annoying is what you’re saying.

TERESA BEJAN: [LAUGHS] And it’s not all the time. It’s not 24/7, although Williams, himself, seemed to have quite a lot of stamina. But it’s the idea that part of what it is to live in the world is to have the courage of one's convictions and to care for the souls of one's fellow citizens. And if you think you’re right, then you have a duty to try to convince others that they’re wrong.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Politely.

TERESA BEJAN: It’s not that you have to be polite. Indeed, this kind of no-holds barred evangelical debate is going to be the cause of a lot of offense. I think, you know, one thing I think Williams would want us to think about is why we set the standard for success so high.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mmm.

TERESA BEJAN: Surely, un-murderous coexistence, itself, is a precious achievement. And if we keep on making the best the enemy of the good in social life, then we really do risk losing these kinds of, you know, yes, they’re minimal, yes, they seem maybe less than aspirational but that there’s actually something really, really precious about --

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Not killing each other.

TERESA BEJAN: Yeah, this un-murderous coexistence. We can’t take it for granted.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So when applying the lessons of Rhode Island to the nation today, people aren't engaging or complaining or insulting, necessarily, because of beliefs but because of what we’re seeing, because of actions, tearing kids away from families at the border, the destruction of the environment. Do the lessons of civility still apply in this setting?

TERESA BEJAN: Mm-hmm. I mean, one thing worth remembering is that the religious disagreements that are at stake in the 17th century, they’re not just differences of opinion about beliefs, they’re also serious disagreements about how we should organize society, how we should live together.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm. [AFFIRMATIVE]

TERESA BEJAN: Look, you know, I’m offering a theory of civility, not of justice, not of democracy, right? Civility is civility.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: But, actually, civility isn’t civility because just in our discussion we have seen it redefined over and over again.

TERESA BEJAN: So mere civility, on my view, is this conversational virtue that’s minimal conformity to norms of respectful behavior that are needed in order to keep a conversation going, but most fundamental to that is just the willingness to have the conversation.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm. [AFFIRMATIVE]

TERESA BEJAN: We mustn't give up on one another, and that's the kind of evangelical core of mere civility on, on the Williams model.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm.

TERESA BEJAN: It doesn't deny it all the importance of crying out against injustice. Indeed, it accommodates crying out against injustice. But it says that when we call out injustice, we do so in a way that remains committed to sharing our fate in society together.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: I mean, you’ve seen people trying to argue on cable news. Usually, they start yelling and they start talking over each other and then they cut to a commercial.

TERESA BEJAN: All just for the benefit of those watching who agree with them already.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm.

TERESA BEJAN: And I think both sides have so much to learn from a radical obstreperous evangelical Puritan who actually just had the courage of his convictions and just continually had those uncomfortable conversations that every kind of theorist of [LAUGHS] toleration told him were, were impossible. And I think that's the kind of radical hope on which American democracy is really built.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Teresa, thank you very much.

TERESA BEJAN: [LAUGHS] Thank you.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Teresa Bejan is an associate professor of political theory at the University of Oxford and author of Mere Civility: Disagreement and the Limits Of Toleration.