BOB: As we’ll hear more about shortly, it’s plenty terrifying to imagine some cosmological event suddenly robbing us of the ability to access that hilarious video of Uncle Ralph in his scuba gear. But what if the demise of all we hold digitally dear is a disaster of human design; a gradual, rolling crisis, already set in motion? Internet pioneer Vint Cerf is trying to halt that destructive trajectory with a concept he calls “digital vellum.” But it won’t be easy...

CERF: I found that the Internet is a peculiar beast: it it remembers things you wish it would forget and it forgets things you wish it would remember.

BOB: Cerf and other tech thinkers have given the problem of encroaching digital obsolescence the ominous moniker --

CERF: Bit rot! It’s a serious problem, and it comes in several flavors. The first one is the physical media in which we store digital content. It isn't clear how many years they will last, but even if they lasted for you know 20 years, 30 years, there's this question of what can read them.

BOB: I'm preparing for my daughter's wedding and have a whole mess of VHS tapes, which I wanted to harvest for their nostalgia value, but I don't have a VHS player to play 'em on.

CERF: But let's pretend that in fact you've been very careful to copy these digital objects, these bits, from one medium to another so at least you're on a medium you can still read. And then you discover that this digital object was created by a piece of software that no longer runs on the computer that you have. So now we're into a different kind of bit rot: the problem where we don't know how to interpret the bits even if we've carefully saved them.

BOB: Then they may as well not exist.

CERF: That's basically correct. For things that are static, an image or a text file, you can imagine ways of finding alternative software that might be able to render this stuff. But if it's a spreadsheet which is an interactive program that will literally respond to new inputs, you really need the software.

BOB: So tell me about digital vellum.

CERF: Digital vellum is a term actually, it's a made up term, to try to draw people's attention to the need not only to physically preserve bits -- animal skins turn out to be a pretty resilient way of storing written material -- but also to preserve the executable environment so that software that created those bits can still be run. There's a project at Carnegie Mellon, which I learned about in the course of thinking through this digital vellum idea, Professor Mahadev Satyanarayanan, we call him Satya for obvious reasons, basically what he does is take a digital x-ray of the machine that has the operating system running and the application running as well as a description of the way the hardware works. He found a way to capture all that information and then reload it into for example, into the cloud on a virtual machine that emulates whatever the older hardware runs and runs the old operating system and application code, and so it's a brilliant piece of work, but there are some challenges that are not technical that are worth talking about.

BOB: Yeah, I can see one of them right now and that is, who would undertake such a project to be the clearinghouse for software, hardware new and old. A private company like Google, obviously has vast amounts of storage infrastructure, but I'm not sure whether the public wants all of the history of the internet stored in google servers, and I'm not sure if your board of directors wants to pay for that. Then there's government which raises the specter of a whole bunch of other things. Where does this stuff live?

CERF: Well, plainly, you have to have multiple organizations. It may very turn out that no one institution could or should be trusted to save everything forever. And look there's a business model issue here. How do we make this an affordable kind of activity, one which is self supporting or sustainable? And I don't think I have an answer to that, although it wouldn't surprise me if a combination of private sector, not for profit and government institutions become part of a solution. Just as you have libraries, some of which are supported by the federal government, some are supported by local governments, and some are private sector libraries, and so you can see that already in the older media that we have a diversity of investments in preserving information. So, if Google can do its part, it would only be a part of the solution.

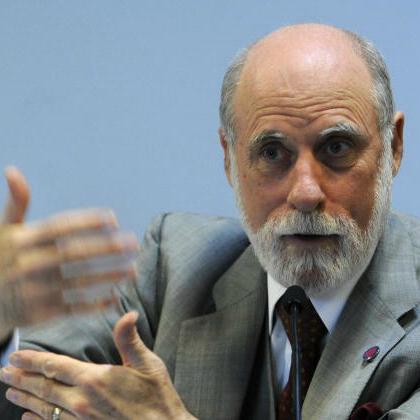

BOB: Vint Cerf is vice president and Chief Internet Evangelist for Google. He disclaims being the father of the Internet, but it does kind of look like him.

CERF: [laughs] Well, I'll tell you what, I'm not the only father of the internet. Bob Con and I did the original design way back in 1973, and then of course by this time millions of people have contributed to its explosive growth. So I'm happy to accept a certain amount of visibility but not all of it.

BOB: Vint, thank you so much.

CERF: Well, it's been pleasure to talk to you about this and I imagine that this might be digitized and we can now ask ourselves a thousand years from now will our descendants listen to this conversation and either say, boy those guys were smart to figure out you know how to solve this problem, or too bad they didn't figure it out and I'm listening to this because it was preserved by accident in a digitized piece of vellum.

BRANDON: Hi, this is Brandon from Senoia, Georgia. My story begins when I was a senior in high school and there was this girl I was trying to court and I used the website MySpace. I remember coming home and really relishing logging onto MySpace and reading her letters and writing her letters. Eventually I kind of figured I'd outgrown MySpace so I randomly kind of deleted my account. And when I told my girlfriend this, her name is Ashley and we're now actually married, she immediately realized that these heralded love letters of our budding romance were gone forever. Even though we've been married for almost three years now, every time you know this comes up, she gets a little resentful that these letters are gone.