Understanding the White Power Movement

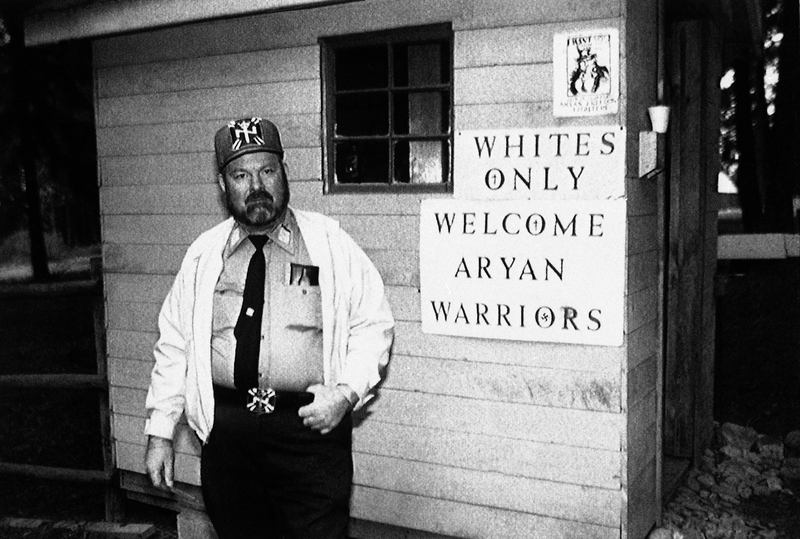

( Gary Stewart / AP Images )

BOB GARFIELD: This is On The Media, I'm Bob Garfield. When events like Christchurch happen, the elements may indeed be obvious. Guns, hatred, alienation but the obvious is also reductive and risks obscuring larger forces at play. The same goes with the vocabulary of race violence–white nationalist, white identity, alt-right, white supremacy, white power. They're used interchangeably, which further clouds the picture. Christchurch, says University of Chicago professor Kathleen Belew, is the latest manifestation not just of resentment and paranoia or even radical racism but a clearly defined revolutionary movement. Kathleen, welcome to the show.

KATHLEEN BELEW: Thank you for having me.

BOB GARFIELD: Why do you specify white power versus, say, white supremacy?

KATHLEEN BELEW: I think the closest term would be white nationalism. But the thing is that when we talk about nationalism, a lot of people think about sort of an overexertion of patriotism. And the assumption there is that the nation implied and white nationalism is going to be the United States or New Zealand. In fact, the white power movement is interested in a trans national white population that is attempting to seize control of first white homelands and then eventually the world as a white nation. And for this reason, I think white power is a better term for thinking about this in our reporting and in our debating because it conveys the radical future imagined by this movement. And I think white supremacy is just overly broad. White supremacy is an ideology held in common by many people who have less extremist and less violent political ideologies and also white supremacy of course describes many elements of our governance, our distribution of resources, our criminal justice system our courts. Right? So being specific about the radical nature of this movement is important.

BOB GARFIELD: It's obvious that white racism goes back centuries, in this country and abroad, but you place the white power movement at a particular place in American history, namely the end of the Vietnam War. Why then?

KATHLEEN BELEW: So the Vietnam War created a narrative about betrayal by the state that brought Klansmen, Neo–Nazis, followers of Christian Identity, skinheads, radical tax protestors, white separatists and more, into this common cause. And this was accomplished both by a sense of profound distrust in the federal government and other sort of institutions, and also mobilized by fears of racial annihilation, fears of the end of the white race and being overrun. The Vietnam War is also important here because it dramatically escalated the impact of this movement on civilians because the white power movement was able to mobilize the weapons and tactics of that war in a kind of paramilitary activism that came home to the United States. I should clarify a little bit what I'm saying because the number of returning Vietnam veterans who joined this movement is very, very small–statistically insignificant even. But the veterans who did join white power groups had enormous impact on their social and cultural formation and also on the strategies and weapons that they use.

BOB GARFIELD: Now this period that you describe, post Vietnam War, occurred just before the Reagan administration, which was very conservative and kind of big government hating. And you would have thought would have been a very satisfying political outcome for the people we're talking about. But no, au contraire.

KATHLEEN BELEW: So this movement turned revolutionary in 1983. It declared war on the federal government and began a string of infrastructure attacks, assassinations and other actions that were intended to foment race war. The fact that that happened as you say during the second term of the Reagan administration and not under a leftist executive indicates that having what people in the center might perceive to be a friendly administration is not going to be enough for activists and this kind of an ideology. They look at someone like Reagan and see him as moderate. They see frustration with the distance between campaign promises and what people can actually put through. And they sort of see this as a referendum that electoral politics are never going to achieve the kind of radical social change they want.

BOB GARFIELD: I want to talk about ideology for a moment. A recurring theme, it seems to me, is this notion of white genocide. And with that paranoiac worldview, a certain word keeps popping up.

[CLIP]

CROWD: You will not replace us! You will not replace us! [END CLIP]

BOB GARFIELD: Replace us–what does that even mean?

KATHLEEN BELEW: People in the white power movement see a whole number of social issues as fundamentally being about a threat to white reproduction. Abortion is a threat because it might kill white children. Immigration is a threat because of the threat of hyper fertile populations of color overrunning a white nation. LGBT rights and feminism are a threat because they might encourage white women not to bear white children. All of this is felt not as a soft demographic change but as a real apocalyptic threat.

BOB GARFIELD: But let me just observe that it's not just mass murders in New Zealand or Nazis in Charlottesville, Republican Congressman Steve King said on Twitter quote 'we can't restore our civilization with someone else's babies.' And here's right winger Laura Ingraham on FOX this week.

[CLIP]

LAURA INGRAHAM: Democrats were once the party of ideas, the party of the little guy. Well, the little guy is actually doing much better under Trump and they know it. So what's their answer–to replace you. [END CLIP]

BOB GARFIELD: Is there more danger from terrorists or from this ideology seeping into the political mainstream?

KATHLEEN BELEW: Here's one way to think about it, the white power movement is a tiny group of people. In the period of my study, we're only talking about 10 to 75 thousand people who are in kind of the inner hardcore ring that might carry out an act of violence or support one. Outside of that, there is another, I don't know, 150,000 people who do things that are public facing that are more like attend rallies, by newspapers and agree with the ideology. And outside of that, there's another 450,000 people. Now, those people don't buy a newspaper but they regularly read the newspapers. Right? And there's the diffusion of ideas. So then we could imagine that outside of that, which is now a population that's not usually counted, there are probably a larger group of people who had never read something that says you know newspaper of the Knights of the KKK, but who would agree with the ideas that are presented in one. And you can imagine that this model of organizing works both to push ideas from that hardcore inner circle out into the mainstream and to pull people in towards the middle who can be radicalized towards racist violence. So I think we have to think really carefully about how fringe ideas move and also about the capacity of these groups to continue recruiting people to do harm.

BOB GARFIELD: On the subject of relative danger, I when to come to the question of leadership. The Oklahoma City bombers didn't have a boss, Dylann Roof didn't have a boss, the Christchurch shooter didn't have a boss, and yet they're responding to some things central. What and how?

KATHLEEN BELEW: They're responding to a coherent political ideology that lays out a plan of attack. One of the places that we can see this is in the dystopian novel that becomes not only a manual for the movement but kind of an ideological lodestar it's called The Turner Diaries and it's published in the late 1970s and then popularized over the 1980s and foreword. The Turner Diaries lays out this incredibly huge end goal, which is not only the successful takeover of the United States but the annihilation of all people of color, all over the world through nuclear and biological weapons. Group leaders are able to sort of spread this idea, get people organized into cells distribute money to those cells and then connect them through computer message boards and then through the Internet such that all of these things can kind of evolve independently but towards a common purpose. What it shows us is that these acts of violence are never supposed to be the end point in it of themselves, but are supposed to awaken this broader white public into race war.

BOB GARFIELD: The Turner Diaries has become as, you say, a lodestar, an aspiration for gathering race war. Is it happening?

KATHLEEN BELEW: In order to really reckon with this kind of violence, we would need to connect these disparate acts by the ideology of the perpetrators. So rather than reporting on say the attack on the Tree of Life synagogue as an anti-Semitic crime, the attack on Charleston worshippers as a racist crime and the Christchurch shooting as an Islamophobic crime, we really have to look at the fact that all of those perpetrators are motivated and connected by the same ideology, the same kind of view of what their violence is supposed to do. We could add many more episodes to that list and do the work of connecting these dots together. Certainly things like the Oklahoma City bombing and Anders Breivik attack in Norway would belong in that same story. Doing that would create a different kind of reporting that doesn't rely on the idea of lone wolves but actually does the work of connecting these events together. It would allow a different kind of public conversation about what these events mean. And it would create a different kind of expectation about what kind of surveillance and legal resources need to be dedicated to this moving forward.

BOB GARFIELD: Elsewhere in this program, we're considering the other edge of this double edged sword, however, and that is with the increasing attention we are boogying the very movement that we're trying to isolate and understand. How do you square that circle?

KATHLEEN BELEW: I profoundly disagree with the idea that we should not talk about this violence. We should call this a manifesto because it is a political ideology and we should understand it as such. I believe we should name the gunmen because this is part of a historical project of connecting these acts of violence together. And I also think, not for nothing, this movement wants us not to understand it as a movement. This movement has worked incredibly hard for several decades to appear precisely as the acts of disconnected mad men rather than as a groundswell. The term lone wolf was coined by people in this movement in order to muddy the waters about prosecution and public understanding. When we report this as the work of single actors even of cells, what we're missing is a huge component of the organizing which involves deep social ties. This is a movement that rests just as heavily on things like shared childcare and home school curricula as it does on leaderless resistance and lone wolf violence quote unquote. We have to understand all of it in order to organize any kind of social response. And I'll say this too, there have been copycat attacks after all of these acts of violence there are people who will want to emulate the Christchurch shooting just as they attempted to do that after the actions of the order in the 1980s or the Oklahoma City bombing. We cannot unring the bell of that viral video. This person is already enshrined in various corners of the Internet but social response, really understanding what this is and devoting appropriate resources and time to combating this violence, we have to understand it.

BOB GARFIELD: Kathleen, thank you very much.

KATHLEEN BELEW: Thank you.

BOB GARFIELD: Kathleen Belew is a Professor of History at the University of Chicago and author of Bring the War Home: The White Power Movement and Paramilitary America.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]