A Trip Through Wild Wild Country

BROOKE GLADSTONE: This is On the Media. I’m Brooke Gladstone.

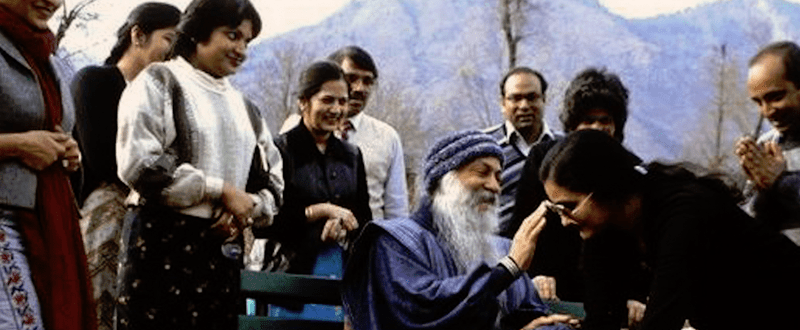

BOB GARFIELD: And I’m Bob Garfield. When the six-part documentary series Wild Wild Country came out on Netflix last month, it was like a blast from an unremembered past. Back in the early ‘80s, thousands of followers of the Indian guru Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh descended on an Oregon ranch the size of Tallahassee, Florida to found their utopia. The Rajneeshees had millions of dollars and a lifestyle based on meditation, consciousness-raising and free love. It was all irresistible to the young American and European followers and increasingly alarming to their closest neighbors in the tiny town of Antelope, population 40.

What followed was an epic struggle between the Rajneeshees and every level of government. That struggle involved elections, a relentless media campaign, arson, a mass poisoning, political assassination attempts and the recruitment of more than 5,000 homeless people from around the country. We won’t talk much about that -- no spoilers here -- but there’s plenty we can say. Maclain and Chapman Way directed Wild Wild Country. Hey, welcome to OTM.

MACLAIN WAY: Thanks, Bob. Thanks for having us.

CHAPMAN WAY: Thanks for having us on, Bob.

BOB GARFIELD: This is a [LAUGHS] wild, wild story. These people, all dressed in varying shades of red, came to Oregon, to this barren land, and they built their own city, including streets, waterworks, public transportation, shopping centers, houses, police force, even an airstrip. And then chaos ensues, and you have the entire story from every angle, on tape! How did that happen?

MACLAIN WAY: Yeah. Luckily, news directors in the Portland area, I think they knew what a significant historical story the Rajneeshees were and the story of Rajneeshpuram, so they kept all their raw tapes, which was incredibly rare because we weren’t just working with what ended up on the nightly news every night, we were working with what the cameramen who drove down to the ranch shot. And that ended up being 300 hours of archive footage. And then the group themselves, the Rajneeshees, they would edit these ranch promo documentaries, 10 to 15 minutes long, that we had gotten access to. So we literally almost had footage for everything we wanted to tell.

BOB GARFIELD: There are a lot of characters in this story. There’s the Bhagwan himself, in flowing robes. There’s his secretary, kind of a chief of staff and spokeswoman, a tiny and very feisty young woman named Ma Anand Sheela.

[CLIP]:

MA ANAND SHEELA: Free sex? We don't charge for it, if you mean that.

INTERVIEWER: Right.

[AUDIENCE LAUGHTER][END CLIP]

BOB GARFIELD: There were a few extraordinarily eloquent followers who you spent hours interviewing.

[CLIPS]:

MA SHANTI BHADRA: I approached Devaraj and said something into his ear and as he leaned towards me I pushed the syringe.

BOB GARFIELD: Some nearly as eloquent local town folk in Antelope.

JOHN BOWERMAN, RANCHER: They all had something that we referred as “the look,” almost like under the influence…

BOB GARFIELD: Some really determined politicians and prosecutors.

LYNN ENYART, HEAD OF FBI TASK FORCE: We had no idea that we were going to run into the largest poisoning case in the history of the United States.

[END CLIP]

BOB GARFIELD: It’s often very difficult to identify the protagonists.

MACLAIN WAY: Yeah, exactly. We were exhilarated by this idea that most of our audience are gonna come with little familiarity with the story and probably at one point they're going to start leaning on maybe one person's perspective or one side's perspective. But hopefully 10, 15 minutes later, as you’re hearing new information, you’re questioning the position you just took. And I think we were interested in doing that, not just for the sake of being objective, although that's nice, but we actually thought that was an entertaining kind of way to structure the series, which is audience members doing kind of detective work, not in terms of whodunnit but where do I draw the line on who’s good and bad in this story and what is the difference between a cult and a religion and where do I determine my moral compass on the difference between right and wrong?

BOB GARFIELD: Now, if peaceful coexistence between Rajneeshpuram and Antelope was the original goal for everybody, it sure didn’t last long.

[CLIP]:

WOMAN: The Rajneesh have taken over. They’ll make the state red if somebody doesn’t do something to stop them.

BOB GARFIELD: Which triggered most of the craziness that was to follow.

CHAPMAN WAY: This is Chapman speaking. When we started doing the research, we found that, like, the first real line that was drawn in the sand between these two groups was over land use. They didn’t know this but other than Hawaii, Oregon had the most strict land use laws in the country, and the plot of land that they bought, the Big Muddy Ranch that was 64,000 acres, was zoned for exclusive farm use only, which limited, like, what kind of buildings you could have on there, how many houses you could have on the property. And so, very early on the cofounder of Nike, Bill Bowerman who shared a property line with this commune, starts putting together this legal defense with an environmental group called Thousand Friends of Oregon to dismantle the city. And for this group who had just spent $125 million building their utopia, they saw it as an act of survival to go in to the closest town to them, which was Antelope, which was 19 miles away, and buy up all the for-sale property, move in their own followers to the community and then they would, therefore, be able take over political control of the town, which would allow them incorporation rights, which would allow them to build their businesses, it would allow them to have their church there in town. And so, they moved over 60 followers into this very conservative cowboy ranching town of Antelope and basically took it over.

MACLAIN WAY: One of the interesting parallels that we found in the series was on first glance the cultural divide between these groups is so vast but Antelope was a very religious town that had transformed their barren wasteland into their little city, and they had a church right in the middle of town and had prayer in public school. And, and these were, by and large, frontier townsfolk that aren’t looking for handouts, sort of pull- yourself-up-by-your-bootstraps type people. And the Rajneeshees wanted their own city with their church right in the middle of it and wanted to practice their way of life.

BOB GARFIELD: Another place we see competing narratives is the question of religious liberty. Once the Rajneeshees did amass political power in Antelope, they were in a position to use local institutions, the schools, the police, whatever, in service of their community. And the Antelopeans, therefore, argued that the Rajneeshees were violating the separation of church and state.

[CLIP]:

MAN: The school is permeated with religious symbolism. It did not look, sound or feel like a public school.

BOB GARFIELD: But then you hear the Bhagwan’s lawyer point out that that problem doesn’t seem to apply to Mormons in Utah or Catholics in Boston.

MACLAIN WAY: You know, most Americans are familiar with the separation of church and state but mostly to keep religion out of government. It’s actually a two-sided coin. It’s also to prevent government intrusion on religious rights. And so, the local Oregonians in the government see this as a tool to get rid of this guru, and it is a very convincing argument that they give. They have a public school but all the teachers dress in religious garb. They teach the religious teachings of their guru. Is that really a public school? And by being an incorporated city, it gave them their own police force and access to police database information that should be protected. They have this very convincing argument that this religious group is violating the separation of church and state.

But then you kind of get to flip the coin and you get to see it from the perspective inside this religious community, which is they feel that this is a complete government intrusion on their rights to assembly, their rights to freedom of religion.

CHAPMAN WAY: Which we found fascinating because, you know, in episode one Sheela will tell the audience and certainly what she told us was she went to Montclair State University in New Jersey and so she had some experience in America and she was always in love with the United States Constitution, especially because of its religious freedom protections. And I think that was a big reason why she felt America would be a great fit for Bhagwan. And for that to turn on her and for her to see that the US Constitution was now being used to strike at the heart of her community, that's when you really start to see things kind of ramp up, not just legal tensions but it starts to spill over into physical violence.

MACLAIN WAY: We were less interested in confirming this is evil and more interested in exploring the devastation that can occur with ultimate devotion to one man and what can happen with tribalism.

BOB GARFIELD: One man or one woman.

MACLAIN OR CHAPMAN WAY: [LAUGHS] Exactly.

[BOTH SPEAK/OVERLAP]

BOB GARFIELD: I mean, if there’s a plain villain to emerge in this series, I suppose it’s Ma Anand Sheela. This charmingly pugnacious young woman turns -- sinister, to say the least. And she’s got a little Iago, a little Rasputin, a little Cardinal Richelieu. And, at one point when she doesn't have enough votes to dominate a county election, she hatches a cuh-razy scheme.

MACLAIN OR CHAPMAN WAY: Yeah, so by episode three after this group has taken over the town of Antelope, they now set their sights on taking over the larger surrounding county called Wasco County. They know that they don't have enough people inside the commune to win these Wasco County elections so they need to bolster their voting numbers, and they hatch this plan bus in over 5,000 homeless people from the streets from all over America, Washington, DC, Miami, Skid Row in Los Angeles.

[CLIP]:

FEMALE CORRESPONDENT: In Washington, DC, the Rejneeshees continue to recruit street people with the promise of food and shelter and a free bus ride to Oregon.

MACLAIN OR CHAPMAN WAY: Spoiler alert, it doesn’t work out that well.

BOB GARFIELD: It was bananas. She brought in voters but she also brought in mental health issues, alcoholism, some criminality.

MACLAIN OR CHAPMAN WAY: The other interesting dynamic that had emerged in our archive footage was a lot of these homeless people, they were Vietnam War veterans, and so in their own interviews from the ‘80s they would oftentimes talk about the resentment that they felt towards America. You know, these people dressed in red, there were the first people that were offering them a helping hand. They loved it. They kind of were interested in voting and supporting this community. Yeah, suffice to say, it obviously doesn't work out that well.

Jane, who is a Rajneeshee that was starting to break away from the movement, she would often call this the beginning of the end of Rajneeshpuram.

[CLIP]:

JANE STORK: It was a catastrophe. We had literally thousands of homeless people causing complete chaos. It became clear that we had a hornets’ nest right in the middle of the community.

[END CLIP]

MACLAIN OR CHAPMAN WAY: Overnight almost, there’s a 2 to 1 ratio of homeless people to Rajneeshees. I think that it was beginning to open her eyes up that this isn’t what we started here.

BOB GARFIELD: Let’s just assume that the attention of all of the Rajneeshees was entirely pure, let’s assume that they were just good people who wanted to do something radical and utopian, and along the way they encountered hostile land-use regulations, inconvenient laws, unhappy neighbors, all of the realities of society. And even without the outside world, Rajneeshpuram couldn’t even bear the weight of its own internal contradictions. What does this story tell us about the possibility for any utopian project to gain purchase in the modern world filled with other people?

MACLAIN OR CHAPMAN WAY: You know, I think it’s actually natural that these Antelopeans were scared of these Rajneeshees that came into their town and dressed head to toe in one color and maybe armed themselves with, with AK-47s. I think that's like a natural fear that you have. But then, like, what do you do after that? That's what you're in control of. And the same goes for the Rajneeshees. It’s, like, the anger that they must have felt when their community is being threatened over land use, they felt that they had transformed this wasteland into this utopian oasis, it must have caused an immense amount of rage and anger. But it’s what you do after that.

I think that Sheela’s innate personality, Bhagwan’s innate philosophy was provocation, was controversy. The Rajneeshees, when push came to shove, they certainly shoved harder than anyone else. And I think, obviously, on the Antelopeans, it was the same sort of theme. You know, they were going to do whatever it took to get them out of town.

BOB GARFIELD: One final question. This is On the Media and a hammer thinks everything is a nail, but I contend that this episode in the ‘80s in Oregon is at the core a media story. The Bhagwan captivated the media. Sheela mastered the media with her smile and her bluntness and her seeming never-ending press tour.

[CLIP/MUSIC UP & UNDER]:

MA ANANA SHEELA: No, I’m not running for cover, mister. I don't run for cover. And a person like you make me run for cover? Ah, that’s a joke!

[END CLIP]

BOB GARFIELD: Video, as we discussed, when it’s used as a defensive weapon by the Rajneeshees and as an intimidation tool, as well, newsrooms worldwide followed every development, and yet, so ephemeral. I mean, where did it go?

MACLAIN OR CHAPMAN WAY: [LAUGHS] Yeah.

[BOTH SPEAK/OVERLAP]

BOB GARFIELD: Seventy Rolls-Royces, poisonings, how did it evaporate, ‘til now?

MACLAIN OR CHAPMAN WAY: When we were making the series, everyone was kind of familiar with Jonestown and everyone was kind of familiar with Waco and, you know, people would constantly ask us, like, how do I not remember the story or how do I not know about this story? And, really, I think it was kind of a combination of factors. I think, one, the fact that no one did die, which is remarkable [LAUGHTER], considering the tension out there, there was no bloodshed in this story, which is why I think it kind of got lost to the dustbins of history.

The other interesting thing is when we went through a lot of the media in the ‘80s, this story really was reported as just kind of this bizarre quirky thing that was happening out in Eastern Oregon with this guy and these Rolls-Royces, and no one was really diving into, like, the complexities of this story. And so, I think by the time the commune disbanded in 1985, everyone was, like, oh, that weird quirky experiment is over. Documentary allows you to shine a light on these forgotten stories and reexamine what makes them so profound and what makes them so significant.

BOB GARFIELD: Chapman and Maclain, thank you very much.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

MACLAIN OR CHAPMAN WAY: Thanks.

MACLAIN OR CHAPMAN WAY: Thanks for talking to us. Thanks for having us on.

BOB GARFIELD: Chapman and Maclain Way are brothers and directors of Wild Wild Country, available on Netflix.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

That’s it for this week’s show. On the Media is produced by Alana Casanova-Burgess, Jesse Brenneman, Micah Loewinger, Leah Feder and Jon Hanrahan. We had more help from Philip Yiannopoulos, and our show was edited -- by Brooke. Our technical director is Jennifer Munson. Our engineers this week were Sam Bair and Greg Rippin.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Katya Rogers is our executive producer. Jim Schachter is WNYC’s vice-president for news. On the Media is a production of WNYC Studios. I’m Brooke Gladstone.

BOB GARFIELD: And I’m Bob Garfield.