BOB: Last month, BBC Arabic service head Tarik Kafala spurred a semantical controversy when he announced that the BBC should not refer to those individuals who attacked Charlie Hebdo as “terrorists.” Such a choice, critics said, was “outrageous” and “gives succor to terrorists.” Conservative MP Conor Burns classified the whole affair as, quote, “yet another example of Orwellian, ‘1984’ use of language by the BBC which serves to mask rather than illuminate.” -- though in fact the BBC does use the word terrorism. David Shariatmadari is a deputy opinion editor for the Guardian and author of its “Buzzwords” language blog. He witnessed the outrage incited by the BBC’s Kafala and set out to explore the unique history and nature of a fearful word. David, welcome to the show.

DAVID SHARIATMADARI: Thank you for having me, Bob.

BOB: One of the odd things about terrorism is it is effective only if people are outraged. In a sense it's a crime of violence, but it's also a kind of mass communication.

SHARIATMADARI: Yeah. Possibly the distinctive feature of modern terrorism, it is a form of message sending. In the research for this piece I was reading an article by David Fromkin from 1975 at the peak of the kind of new terrorism which was occurring which targeted civilians. He says, "all too little understood, the uniqueness of the strategy lies in this: that it achieves its goal not through its acts, but through the response to its acts."

BOB: So we're pretty clear, in general terms, about what terrorism is, at least in the early part of the 21st century, and yet it is so fraught that the head of the BBC Arabic service thinks it's best to let the listeners and viewers decide for themselves and for its reporters to use simply descriptive language. Why?

SHARIATMADARI: I mean the BBC are quite clear that words exist already in the vocabulary to describe these kinds of events, whether they be bombings or attacks or whatever, and I think the BBC guidelines describe the word terrorist as a characterization and they don't want to be in the business of characterization, they want to be in the business of description. The word risks becoming a bit of a participant in the cycle of fear and reaction. There's a risk that the word gets used for something beyond that mere factual description.

BOB: Well, clearly it has a history of being abused. The Nazis used it to describe underground groups, partisans and so forth, that attacked Nazi soldiers. And to this day, we see illegitimate states and others using it to describe mere political protesters, so clearly it's abused...but if others are abusing the word terrorism, should the press be intimidated into abandoning a word which means just exactly what it means?

SHARIATMADARI: No, I don't think so. And actually at the Guardian we have a manual of style which doesn't forbid the use of the word "terrorism" but it advises caution and it asks that we use the word judiciously. I think the BBC has made its own decision. I can understand it, but I wouldn't necessarily throw the word "terrorist" out of the lexicon. We just have to be careful with it.

BOB; Now I'm hinging this whole line of questioning on the notion that we all perfectly well understand what terrorism is, and that as long as the press uses it properly and does not allow itself to be manipulated by politicians and others, that it should not be taken from our lexicon. On the other hand, terror hasn't always meant what we understand it to be now. Its roots go back to the original state terrorism, do they not?

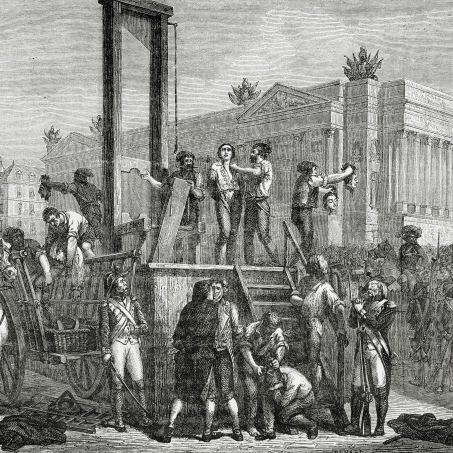

SHARIATMADARI: The word terrorist and terrorism entered the English language at the end of the 18th century at the time of the French Revolution. And it was used to describe the activities of the revolutionary government. The Committee for Public Safety, as it styled itself, which had taken charge in France and conducted essentially a political purge against its enemies. That period became known as the Reign of Terror, and because that climate of fear was attended to by all the other nations in Europe because it was such a tumultuous event, the word entered various different languages: it entered Spanish, Italian, and English. But initially it was used to describe a revolutionary government's activities against its people and against its political enemies.

BOB: And now it's almost entirely flip-flopped: it's used to describe the kind of asymmetrical warfare where people who can't take on a government can nonetheless get the attention of the world by committing various kinds of atrocities and outrages in the way that we've seen ISIS been doing for the last year or so. Since terrorism isn't complete until the reaction to it has taken place, particularly in the press, I'm just curious, if the press actually pulls back on its use of "terrorism" for fear of getting caught up in politics, do the terrorists win or do the terrorists lose?

SHARIATMADARI: If news organizations were going to be more judicious in their use of the word, I wouldn't see that as the terrorists winning against the media organizations. I think it would be at least partly the media organizations deciding not to participate in a cycle of fear.

BOB: David, thank you so much.

SHARIATMADARI: Thank you, Bob, for having me.

BOB: David Shariatmadari is deputy opinion editor on the Guardian's UK Comment desk, and author of the Buzzword series.