The Supreme Court Justice With The Most To Say

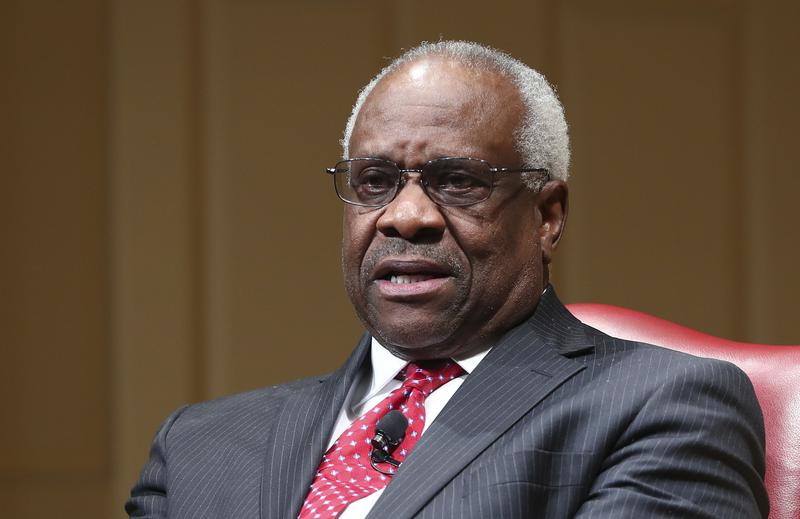

( AP Photo )

BOB GARFIELD This is On the Media, I'm Bob Garfield.

BROOKE GLADSTONE And I'm Brooke Gladstone. So lately we've had a rare chance to see how justice can play out in the streets. But rarer still, almost impossible, really, to see into the heads of the nation's most exalted arbiters of justice in the Supreme Court of the United States. We'll spend the rest of the hour delving into the life, the perspective and the legacy of the current court's longest serving justice, also known to be the quietest on the bench, the most enigmatic and to many liberals, the most baffling. Here, during his 1991 confirmation hearings, Justice Clarence Thomas is queried by Senator Howell Heflin.

[CLIP]

SENATOR HEFLIN What did you major in, in Holy Cross?

CLARENCE THOMAS I majored in English literature.

SENATOR HEFLIN What did you minor in?

CLARENCE THOMAS I think protest [END CLIP].

BROOKE GLADSTONE No longer am I baffled. Having read The Enigma of Clarence Thomas by Corey Robin, author and teacher at Brooklyn College and CUNY Graduate Center, it's altogether clear that Thomas is not merely a black conservative who always seems to argue against leveling America's playing field. In this interview, which first ran in November, Robin explains that Thomas is in fact a black nationalist. It's evident in everything the judge writes in every public pronouncement.

COREY ROBIN He is, in fact, the book opens with an epigraph, the famous line from the opening of Invisible Man. I'm an invisible man and everybody sees everything and anything but me. Clarence Thomas has a very long written record, more than 700 opinions where he sets out

this conservative black nationalism. And it's something that a lot of people have not noticed, the very few who have tend to be scholars of color. But for the most part, the only thing most people know about him is about Anita Hill and the fact that he doesn't ask questions from the bench.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Something you observed very early on is that Thomas and the man he replaced, Thurgood Marshall, were both considered in their day to be intellectual lightweights whose decisions were written for them by other people. And as we later learned in your book, the kind of racism that rankled Thomas most was this constant charge that black people weren't as smart.

COREY ROBIN Exactly. He was a student at Holy Cross and then at Yale Law School beginning in 1971, and he discovered what he felt was a more insidious kind of racism than what he had known in the South. He grew up mostly in Savannah, Georgia. He was used to and familiar the kind of overt hatred of black people by white people. And when he came to the north, he found a more genteel kind of racism that was more liberal, that was more patrician, that was overtly solicitous of black interests, that hid its deeper assumptions about particularly the intellectual inferiority, as you said, of black people. And that's something that Thomas has faced from a very early moment in his career and has taken with him onto the court.

BROOKE GLADSTONE He told the journalist Juan Williams that he preferred dealing with an out and out racist to one who is racist behind your back. As one of his favorite songs went.

[The Undisputed Truth’s “Smiling Faces” plays]

BROOKE GLADSTONE The Undisputed Truth is the band.

COREY ROBIN It came out in 1971, I believe, and he used to listen to it all the time at Yale Law School. And when he was asked about the Reagan administration, which he joined in 1981, and about the racism of the Reagan administration, he said they don't lie to you and also they don't smile at you. This is a very resonant notion for him. And I should say it also echoes a lot of sentiments and beliefs in the black nationalist tradition. Malcolm X spoke about the wolves versus the fox.

[CLIP]

MALCOLM X And we don't think that it is any worse to be bitten with a smile than it is to be bitten with a growl. [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE And his first prolonged confrontation with smiling faces would probably have been at Holy Cross in Massachusetts.

[CLIP]

CLARENCE THOMAS I was out of your writing in 1970 because I was mad at the world. That was cynicism and negativism, eating me up, hatred, animosity. And I felt justified because of all the race issues. I was really upset. [END CLIP]

COREY ROBIN Thomas comes there in 1968. He's a part of a cohort of 18 black men. One of the poorest of that cohort recruited by a very liberal Jesuit who's seeking to integrate Holy Cross. The differential treatment of white and black students becomes very apparent. White students are sent letters in the summer before asking them, would you mind having a black roommate? The black students don't get any such letter at all. The experience of being an almost all white classrooms of reading all white authors of having mostly white music played at campus events. Not having black professors, spurs them to form the Black Student Union. And this is a very deliberate decision and nomenclature they choose. The word Black, at this time, is a kind of more militant affirmation that you hear more on the West Coast than the East Coast. They have a statement of demands and then they issue a manifesto of their own internal rules. Many of which involve, you know, that black men should respect black women. Black men should not be involved with white women. And so it's a whole statement and coherent platform that's very familiar among radicalized black students across America.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Is this when he first encounters or first makes use of the ideas of Malcolm X.

COREY ROBIN Yes, he reads the autobiography of Malcolm X in 1968, starts listening to the records of Malcolm X's speeches.

[CLIP]

MALCOLM X It is better for us to go to our own schools and after we have a thorough knowledge of ourselves, of our own kind, and racial dignity has been instilled within us, then we can go to any one school and we'll still retain our race pride and we will be able to avoid the subservient inferiority complex that is instilled within most Negroes who receive this sort of integrated education. [END CLIP]

COREY ROBIN Nearly 20 years later, when he's giving these interviews to people like Wayne Williams, Thomas can recite from memory various passages from the autobiography and from those records.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Is this when he comes to the conclusion, the crucial conclusion that racism is not really addressable through the courts or through legislation?

COREY ROBIN Yes. We have to remember at this time, there's all kinds of political efforts to deal with racism. Some of it is electoral, some of it is legislative, some of it is judicial, and some of it is much more militant radical action in the streets. And when he comes to buy the sort of early to mid 1970s is a belief that white racism is permanent, pervasive and ineradicable in the United States.

It has roots that cannot truly be fathomed. And because they cannot be fathomed, we can't pull them up. And that once you come to terms with that, several conclusions follow. And the first and the big important one is that the political process, whether it be voting or protest or organizing, that all of this is a misbegotten enterprise that black people should get themselves out of. This explains in part why he almost always comes down against voting rights. He believes that this is a fool's errand. The second conclusion is that capitalism, the marketplace, while it tends to be geared towards white interests, nevertheless offers niches where black people can achieve some kind of measure of autonomy. Specifically black men.

Thomas derives this in part from his reading of Malcolm X. I should say a selective reading, because Malcolm X had a complicated view on this. Thomas also derives this from reading a black economist by the name of Thomas Sole, very prominent conservative, and in Sole, Thomas finds a vision for black people not of emancipation, but of a kind of autonomous space where black people can create their own world apart from white people. So that's the second conclusion that follows from this bedrock principle of the inerratic ability of white racism.

BROOKE GLADSTONE He may have been more receptive to this idea because of the examples set by the most powerful male figure in his life, his stern, humorless but successful grandfather, Myers Anderson.

[CLIP]

CLARENCE THOMAS My wife had a bust of my grandfather made right after I was confirmed and I put it up on a bookshelf where it looks down on me. And he is that brooding omnipresence. And he's looking down on me with one of his favorite sayings inscribed on it. Ole’ man can't is dead, I helped bury him. And here's what I wondered on the days when self-pity is consuming me. I look up at him. How can I complain to him? No education, no father, raised in part by freed slaves in Jim Crow South. He never complained. My grandmother never complained. How can I tell him that as a member of the United States Supreme Court, I can complain? [END CLIP]

COREY ROBIN Part of Myers Anderson's whole gestalt, was a refusal to look to any kind of benevolence, help or aid from white society through that kind of self-reliance, that very stern iron discipline. He created a world for his family that was relatively safe and spread that protection and largesse to other parts of the black community.

And so this spirit of what in the tradition is called do for self, a kind of collective self-reliance, looking inward to the community and particularly to very strong, powerful black male figures is something that Thomas learns very early on.

BROOKE GLADSTONE And of course, in his college years.

[CLIP]

MALCOLM X Once you can create some employment in the community where you live, it will eliminate the necessity of you and me having to ignorantly and disgracefully boycotting and picketing some cracker someplace else trying to beg him for a job. Any time you have to rely upon your enemy for a job, you're in bad shape. [END CLIP]

COREY ROBIN In the mid 1970s, Thomas makes his right turn toward more conservative principles, and the key element is some of those principles that we just heard in Malcolm X. This belief in creating black institutions that are primarily economic and that this creates a kind of autonomy, even semi sovereignty, separate from the helping hand of white people. His real audience, he's said, is a potential black community that would embrace his ideas to stop looking to politics, to the Democrats, to liberalism as the path forward.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Coming up, more of my conversation with author Corey Robin. This is On the Media.

BOB GARFIELD This is On the Media, I'm Bob Garfield.

BROOKE GLADSTONE And I'm Brooke Gladstone. So when Clarence Thomas arrives on the court, he carries with him a vision of the nation and its history and of human nature. So remorselessly painful that the only way out is through more pain. Author and educator Corey Robin, whose latest book is The Enigma of Clarence Thomas, explains.

COREY ROBIN So Thomas believes that black people, all black people in the United States are surrounded by a stigma of intellectual inferiority. That they are simply not capable is the belief among white people of any kind of achievement or advancement on their own. Thomas does not believe affirmative action created that stigma, but that affirmative action reinforces that stigma. It stigmatizes all black people with that notion that but for the help of white people, they could have never gotten where they are. And in this regard, he thinks that affirmative action stigmatizes it in the same way that slavery did. It didn't matter under conditions of slavery, whether you are free black person or an enslaved black person. All black people were stigmatized with that sense of inferiority. And Thomas believes that affirmative action continues that. And that makes his decisions on affirmative action very different from other white

conservatives on the court who emphasized this vision of colorblindness, that all people are equal and ought to be treated equally. For Thomas, it's an almost literal continuation of the kind of stigmas that black people have been subjected to throughout the ages of American history. And one last point. When white liberals say the difference with affirmative action is that unlike Jim Crow or unlike slavery, affirmative action is designed to improve the conditions of African-Americans to get us beyond race. Thomas will point and cite chapter and verse from white slave holders and defenders of segregation who made very similar claims about their systems. That they were overwhelmingly for the benefit of black people. So Thomas is not impressed by that argument. And then the last piece of his attack on affirmative action is that affirmative action is very much a white program for white people.

BROOKE GLADSTONE That was fascinating in your book. Basically, affirmative action enables an institution, say, an Ivy League school, to keep its same elitist, selective, perhaps white supremacist admissions policies in place while tinkering around the edges that it basically offers a fig leaf.

COREY ROBIN Yes, because he says if you really wanted to diversify yourself, the simplest, most effective, most efficient way is to change your admissions standards, not to rely on things like the LSAT, for example, which Thomas says everybody knows are racially skewed and racially biased. So change your admissions standards and you could instantaneously become a more diverse institution. But those institutions don't want to do that. And so they come to rely on affirmative action, which, as you say, allows them to tinker around the edges. The other thing that affirmative action allows these white elites to do is to choose that black person that they think could be one of us. It enhances the discretionary power of white people. And to Thomas, this has a kind of terrible resonance with America's racial patterns of the kind of the white paternalist choosing among those black people upon which they choose to cast their favors. And that's what affirmative action is for him in the very last piece of this, that this is all part of white elites self conception. This is kind of cosmopolitan, tolerant, multicultural aesthetic. And that's actually the word that Thomas often uses.

BROOKE GLADSTONE It makes them look better.

COREY ROBIN That's exactly what Thomas says.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Let's go to decisions that speak to the second part of your book, Capitalism. He said that money enabled rich people to purchase politicians as mouthpieces for

their points of view and that this is perfectly legitimate. And since black people will never be able to dominate power under the system of majority rule. Money was the only way. And that led him to the decision he took on Citizens United.

COREY ROBIN In the 1987 speech he gives, he says, what we need to do is to remove the stigma of shabbiness that surrounds wealth, particularly among liberals. To make the amassing of wealth almost as sacrosanct as speech itself. Liberate commercial pursuits and make them seem moral. And if you read that speech in 1987, the redistribution of money as speech is his grandfather. Who amassed resources and power for himself and his family and the black community. And Thomas says, you know, liberals would essentially dismiss my grandfather as a nothing. But this is the kind of black man upon whom the salvation of the black race depends.

BROOKE GLADSTONE So, the third part of your disquisition on Thomas is titled The Constitution. You know, as others have, that really we function under two constitutions, the one before the civil war and the one after.

COREY ROBIN Yes. And I call this the white constitution and the black constitution. And Thomas says that the second constitution, the one that was created by the civil war and reconstruction, fundamentally transformed the state. And Thomas believes at the heart of that black constitution is this figure of the black man whose most precious freedom is the right to bear arms. There is also that first constitution that you mentioned,.

BROOKE GLADSTONE The slave document.

COREY ROBIN Yes, this is the constitution that Clarence Thomas, states forthrightly, was created by slave holders and racists. Now, one would think that Thomas would want to have very little to do with that constitution. But that's not the case. And I think here we come to the heart of the most unsettling parts of his vision. He has said the salvation of the black race depends upon black men and that one of the byproducts of liberalism was what he calls the rights revolution. These rights made life easier and more tractable. And black men began to disintegrate. They lost their authority. They lost their will. They lost their discipline. And the results for the black community are catastrophic.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Because the burdens they faced were so much greater.

COREY ROBIN Exactly. So it, Thomas believes, is that we need to recreate those conditions of exigency and constraint and adversity. Because under the harshest, most exigent conditions, black men will rise to their potential greatness. They will overcome precisely in the way that his grandfather overcame.

BROOKE GLADSTONE How does it play out in his decisions?

COREY ROBIN In order to recreate those conditions, Thomas also tries to enhance the white constitution, the antebellum constitution. And one of the features of that constitution were harsh conditions of punishment. And Thomas believes that one of the most terrible things the Warren Court did, the liberal Warren Court of the mid century, was to mitigate the conditions of punishment. To introduce the federal courts, to oversee the practice of punishment and imprisonment. That should be the province of local governments and states. And Thomas would like to actually empower the state to punish. Even if and sometimes it seems, particularly if that state is racist.

BROOKE GLADSTONE That's perverse.

COREY ROBIN It's the most unsettling part, I think, of Thomas's vision, but it comes from this idea that it was under Jim Crow when black men rose to the level that someone like his grandfather did and were able to create enclaves of black autonomy and black separation and black community.

BROOKE GLADSTONE He talked about black men. What about black women?

COREY ROBIN There is very little room in this vision for black women. Black women at best are the recipients of the beneficence of black men. But at worst, black women he views as very dangerous figures. Either the dependance upon the welfare state, which is how he dismissed his sister, that she's so dependent upon welfare, she gets mad at the mailman when he's late with her check. As black feminists like Kimberly Crenshaw and Nell Painter pointed out at the time of his hearings, Thomas's view of his sister was not only extraordinarily ugly and cruel, it actually did not account for the fact that she was one of the pillars of the black community and the black

family. That she maintained the black community, and the black family through her efforts with minimum wage jobs. But black women, as I say, they've played very little in this romantic fantasy that Thomas has. Sometimes when they appear, they're also perceived to be traitors. And that's where I think we come to the question of Anita Hill.

[CLIP]

ANITA HILL Telling the world is the most difficult experience of my life. But it was very close to having to live through the experience, that occasion, this meeting. [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE Anita Hill, a lawyer who worked under Clarence Thomas when he was working for Reagan, who charged him with a number of incidents of sexual harassment.

COREY ROBIN And it's how we mostly remember Clarence Thomas in this country. He responded to the charges not simply by denying them, but by really going on the offensive in the attack.

[CLIP]

CLARENCE THOMAS It is a message that unless you kowtow to an old order, this is what will happen to you. You will be lynched, destroyed, caricatured by a committee of the U.S. Senate. Rather than hung from a tree. [END CLIP]

COREY ROBIN While Thomas was definitely lying about what he did and didn't do with Anita Hill, I don't think he was lying when he made that charge in the following sentence. At the heart of Thomas's vision is black male authority. And Thomas believes that white liberalism has been an essentially a conspiracy to take down black male authority. And so when he saw the Democrats and liberal groups in alliance with this black woman, he saw everything that he had been narrating in both public and private about the way the deck is stacked against black men who are trying to advance the race. And in that sense, Thomas was telling his truth. Revealing in very plain terms what is at the heart of his entire constitutional vision, which is the attempt to preserve the role of black men.

BROOKE GLADSTONE And being utterly blind to the even higher barriers faced by black women.

COREY ROBIN Absolutely.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Did you come away from this project with any more sympathy for Clarence Thomas?

COREY ROBIN I think whenever you write about anybody, you have to have some degree of imaginative sympathy. But actually, I think I came away more horrified in a way, by Clarence Thomas. All countries like they're monsters. But the true horror of a monster is when they reveal a kind of truth about a larger world. And I think when Thomas begins with these very deep beliefs and racial pessimism, the fact that black people cannot be accommodated by a white society.

BROOKE GLADSTONE And are better off if unboundedly repressed.

COREY ROBIN And that's the monstrosity of it all, is that he begins with beliefs that I think are widely shared. And he follows them to conclusions that are not simply horrifying, but which actually do reflect the world that we live in today. Where people are armed to the teeth, where white racism seems almost worse than ever, where wealth is accumulated in even more obscene ways. And where black men are locked up in jails. This, in a way, is Clarence Thomas's preparatory vision to some kind of path out of it. And it's a very dark vision.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Here's Senator Howell Heflin during Clarence Thomas's confirmation for the Supreme Court.

[CLIP]

SENATOR HEFLIN Some believe you, a closet liberal. And so more near the hand that you are part of the right wing extreme group. Can you give us any answer is what the real Clarence Thomas is like today.

CLARENCE THOMAS I don't know that I would call myself an enigma. I'm just Clarence Thomas, and I try to do what my grandfather said, stand up for what I believe. And there's been that measure of independence. But by and large, the point is I'm just simply different from what people painted me to be. And the person you have before you today is the person who was in those army fatigues, combat boots. Who's grown older, wiser, but no less concerned about the same problems. [END CLIP]

COREY ROBIN That young man in army fatigues and combat boots, who is a black power devotee and afficionado, has undergone some fundamental changes in terms of his beliefs about capitalism and so forth. But at the heart, that vision of racial pessimism, which Thomas has never been shy about. Has always been there.

BROOKE GLADSTONE We began talking about The Invisible Man, one of Clarence Thomas's his favorite books, in this, at least he was certainly right. He never really was an enigma at all. It's just that so many of us liberals were outraged by a black man not pursuing civil rights in a way that made sense.

COREY ROBIN For many white liberals, Clarence Thomas doesn't make any sense at all. Once you look at African-American intellectual history and political history, Thomas's views are actually quite legible as part of a tradition. So the real enigma that I came to in all of this is not Thomas's beliefs, but the fact that white people continuously seem incapable of seeing those beliefs. And as I say in the book, there is this character in American literature whose experience looks remarkably like that. And that, of course, is Ralph Ellison's invisible man. And it's not just the fact that the invisible man is not seen. It's that white people think they do know who he is. And they haven't got a clue.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Corey, thank you very much.

COREY ROBIN Thank you.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Corey Robin is the author of The Enigma of Clarence Thomas. We first aired this interview in November.

BOB GARFIELD That's it for this week's show. On the Media is produced by Alana Casanova-Burgess. Micah Loewinger, Leah Feder, Jon Hanrahan, Xandra Ellon and Eloise Blondiau with more help from Eleanor Nash.

BROOKE GLADSTONE On the Media is a production of WNYC Studios, I'm Brooke Gladstone.

BOB GARFIELD And I'm Bob Garfield.

Copyright © 2020 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.