************* THIS IS A RUSH, UNCORRECTED TRANSCRIPT *****************

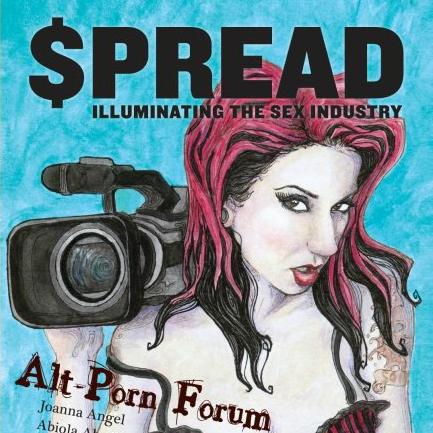

BROOKE: This is On the Media. I’m Brooke Gladstone. The magazine called $pread (spelled with a dollar sign instead of an “s”) was a groundbreaking magazine for and by sex workers that was published from 2005-2011.

When it won an Utne Independent Press Award for “Best New Title”, the judges wrote: “sit down with an issue of this already controversial title and you’ll realize how effectively the mainstream media have denied sex workers a place at the table. Smart and culturally revealing, this quarterly magazine aims to educate, inform, and provoke discussion about the state of sex work.”

A new book has collected the greatest hits from $pread. It’s called $pread: The Best of the Magazine that Illuminated the Sex Industry And Started a Media Revolution. Eliyanna Kaiser was $pread’s executive editor and Rachel Aimee is a founding editor. She explained why they created $pread.

AIMEE: We were all frustrated with the extreme versions of sex workers - it was either the high class call girl making $1000 an hour or the drug addicted trafficking victim working on the streets. And we really wanted to create a space for sex workers to speak for themselves.

BROOKE: So give me a sense of what might be in a typical issue.

KAISER: We largely focused on women's magazines as sort of a template - when we thought about sex workers workplaces, the kinds of things that were passed around or hanging out at the strip club change room or the dom's phone center, we were women's magazines.

BROOKE: But are we talking about Seventeen or Vogue or Cosmopolitan?

KAISER: We're talking about Cosmo and Us Weekly. We wanted to make sure there was a political bent to it, but we wanted to present the magazine in an accessible format. We knew that that was an accessible format. So we had fashion stuff, we had a style section, we had a consumer report where people reviewed products that they used in everyday life. We had this one column where we asked people to write in about the strangest, funniest thing a client ever asked them to do. And there were so many people that told us that that was the first thing they turned to every time they got the magazine.

BROOKE: Give me an example.

KAISER: "F'ing the movement," by a contributor named Eve Rider, and that piece is about a New York City escort who's asked to dress up as an anarchist protest. This client had a fetish about spanking a Seattle protester. I believe there's a line in there "bad protestor - you smashed the Starbucks" - I mean it was just a really really fun column.

BROOKE: I want to get back to the depiction of sex workers in mainstream media and how you wanted to address the stigma and the familiar narratives. There's a reference in the anthology to the "savior narrative." What is the savior narrative?

KAISER: There is a certain kind of mostly male reporting that's going on that is fulfilling its own kind of fantasy, which is this fantasy of rescue. I mean I think it's best embodied in the person of Nicholas Kristof at the New York Times. Whether or not he has the best interests of trafficking victims at heart, at the end of the day he is using them as props, he's often ignoring economic realities in the places that he walking into. I think it takes a certain amount of a personal savior complex to think that as a journalist, you should go and live tweet a brothel raid. You should also know about A&E reality show called 8 minutes, and this is an excellent example of media's obsession with rescue. A former police officer who is now a pastor having tricked sex workers who are advertising in newspapers or on Craigslist into meeting him in a hotel room where they have cameras set up. He has, and this is the point of the show, 8 minutes to convince them to leave their horrible, horrible lives, all for the viewer's entertainment.

BROOKE: Now, a watershed moment for the publication happened when you decided to take an editorial position, that you wouldn't take an editorial position on political or ethical issues. And this stemmed from your feeling that your writers weren't necessarily representative of sex workers in general -- that they were too happy.

KAISER: I think that there was never a moment where the magazine was completely filled with happy hookers or anything like that. But there was a reaction going on to mostly, I think, not the media, but the feminist movement, who was telling them, you are a victim. And I think quite understandably, as a result of being told you were a victim, and there's nothing you can say that isn't, you know, a result of brainwashing, they wanted to very emphatically say, no, I make choices, and life may not be perfect for me, but they are my choices. Did that mean that they were self editing sometimes? Sure. Absolutely. But we definitely made an effort to reach out to people who had as diverse experiences as possible, and to make it clear to them, that they didn't only have to write about things that were positive about their lives, and that they weren't going to be judged for it.

AIMEE: I remember we had a conversation at one point about whether we were going to call the magazine a feminist magazine, because many of us who were involved in the magazine identified as feminists. There was one time where I interviewed Tracy Kwan, she's a novelist and a former call girl. She said being a feminist is often a sign that you were raised in the suburbs or had an unnatural relationship to your mother. We got a letter from Lisa Jervis who was one of the founding editors of Bitch magazine, which is a feminist magazine, she was horrified that I hadn't challenged Tracy on the comment she made. And our response to that was, well, Tracy is a sex worker and $pread is a magazine to provide a place for sex workers to speak for themselves regardless of their opinions on anything. A sex worker thinks this, so it goes in the magazine.

BROOKE: many people were surprised when you were at a national sex workers conference in 2006 that when asked to sign onto a statement about decriminalization of prostitution, you said no.

AIMEE: Mhmm.

KAISER: Yeah, that was probably the most awkward moment and the biggest test of our no positions position. There wasn't a person involved in $pread at any point who thinks that prostitution should be criminalized. But we knew that there were probably some sex workers who might hold a different view. And we wanted to make sure that anyone who was a sex worker regardless of their political views felt comfortable thinking that $pread was a place where they could have a voice.

BROOKE: How has media's coverage of sex work changed with the times? Has it gotten any better since you folded in 2011?

AIMEE: There are definitely more sex workers making their own media these days. Creating media online, and working as journalists. And also the mainstream media tends to use the word sex worker much more than they did 10 years ago.

BROOKE: In the $pread anthology, you anatomize the coverage of the Eliot Spitzer scandal of 2008.

KAISER: What Carolyn Anders is saying in this piece which is called "The Real Media Whores" is that, you know, whenever there is this kind of a scandal, there's this formula that gets rolled out. You find some prostitutes, you ask them about how prostitution works, what the going rate is these days, those are the questions you ask the sex workers. But for the real issue based stuff, you find experts, quote on quote.

BROOKE: Sociologists, doctors...

KAISER: Absolutely. You don't go to the sex workers to ask them the big questions.

BROOKE: One thing I thought was really interesting that was noted by Carolyn Andrews is that the focus is always on the sex worker. The essay quotes Stacey Swim's sex worker blog Bound Not Gagged, who observed that no one called Eliot Spitzer's parents to find out how he grew up to be a John.

KAISER: Nope, but they certainly called Kristen's.

BROOKE: Thank you both very much for being here. Rachel Aimee is a founding editor of $pread magazine.

AIMEE: Thanks for having us.

BROOKE: And Eliyanna Kaiser was its executive editor. Thanks, Eliyanna.

KAISER: Thanks, Brooke.