BROOKE: But as Bob earlier alluded to, it might not be technological obsolescence that divides us from our documents. The cause may not be in ourselves, but in our stars. Or from our star, in the form of a solar flare.

In fact, even as I record this.

FOX NEWS: A big solar storm has happened... And this level of geomagnetic storm is unusual - it occurs for approximately sixty days out of every eleven years.

BROOKE: This week’s flare was large enough to paint the night skies over the northeast and midwest with colorful auroras, rarely seen beyond the extreme north and south poles of the planet. Smaller solar flares actually happen regularly, invisibly and harmlessly, but every once in a while, something massive happens.

In the late summer of 1859, the English stargazer Richard Carrington was busily observing and analyzing solar flares and sunspots, as was his wont. All of a sudden, he saw the sun become dramatically brighter - a phenomenon rarely visible to the naked eye and immediately grasping its importance, says astronomer Lucianne Walkowicz, Carrington jumped up…

WALKOWICZ: ...he ran off to go get somebody - and let this be a lesson to all budding astronomers: never leave the telescope when something exciting is happening because it was over when he got back. [laughs] But the effects of the Carrington event were really quite astonishing. The main form of communications technology in 1859 wa the telegraph, and this event actually induced currents in the telegraph wires that actually caused telegraph paper to catch on fire, the aurorae were so bright that in the northern latitudes you could read by them at night, and they were even seen down by the equator which almost never happens.

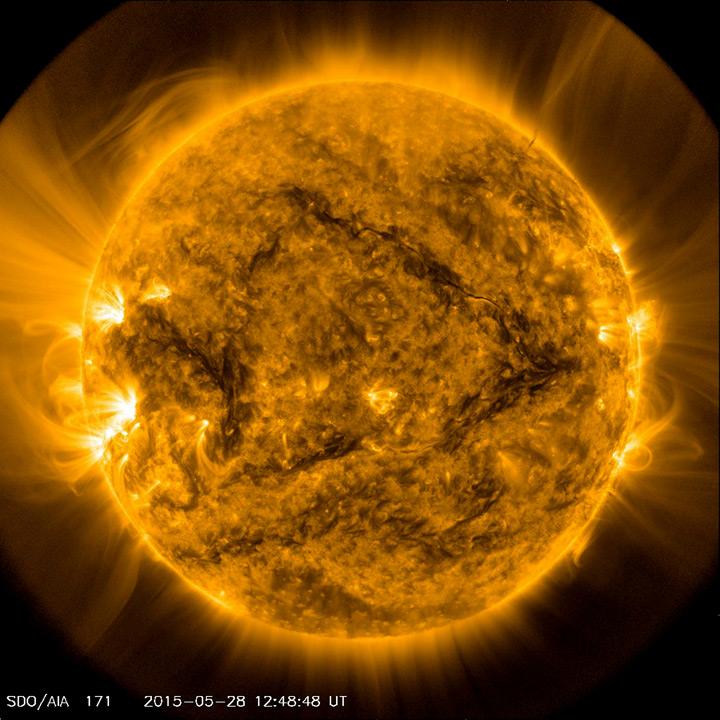

BROOKE: Would you describe what a solar flare is?

WALKOWICZ: Sure! Much like our planet has a magnetic field, the sun itself has a northern pole and a southern pole and magnetic field lines that come out of it. But the sun is not a solid object, the sun is essentially gaseous. And that means that the whole sun spins as a top with different latitudes rotate at different rates. That causes the magnetic field lines to become tangled, almost like a twisted ball of yarn. And so the surface of the sun is actually speckled with these tangley looking magnetic fields which protrude from the surface and create these loops. Now those loops themselves again like yarn or elastic or something like that, sometimes they snap, and snapping of those field lines is what we know as a solar flare. This sometimes flings out actual material or the solar plasma in the form of what we call a coronal mass ejections.

BROOKE: Do we get chunks of the sun hitting earth?

WALKOWICZ: I don't like the word "chunks' just because it sounds like something almost like a meteor or something like that. our planet has this magnetic field which forms a sort of you can think of it as a shark cage. So when we have that material fly off of the sun and come toward us, the magnetic field of the earth deflects those particles down towards the poles of the planet. That can cause the actual atoms and molecules of our own atmosphere to glow or fluoresce, and so that's what we're seeing when we see the aurora borealis.

BROOKE: So that's really beautiful., but we also get things like blackouts

WALKOWICZ: When we have a solar flare, if you have magnetic material coming off the sun and it actually impacts with the planet, it can do things like induce currents in you know infrastructure here on earth. So sometimes that means relatively minor interruptions, but sometimes it can blow transformers, and large parts of the power grid can go down.

BROOKE: I want to play you something. this is a clip from the history channel's 2007 documentary series that was called the Universe. This from the episode called "Secrets of the Sun" and they cast the implications of a modern day solar flare in a very dramatic light.

CLIP:

Imagine if we lost all the satellites that relay cell phone calls, television signals, and bank transactions. And what if at the same time, the failure of power grids cascaded whole regions into darkness for hours or weeks. If these essential services couldn't be restored quickly, chaos wouldn't be far behind.

BROOKE: Dogs and cats living together, mass hysteria! No, seriously, do you think they're gilding the lily here a little?

WALKOWICZ: Well, I mean I think it's fair enough to ask what would happen if all of those things happened? Personally I take a scientific approach. Let's not find out! [brooke laughs} Let's make sure! In the case of a large solar flare would be unlikely that for example your laptop would get fried because your laptop is probably plugged into a surge protector. But, the ability to transmit data doesn't do you any good if you don't have any power with which to do so. the other aspect to this is not just, you know, whether you blow a transformer on the ground, it's also that we all rely on satellite for communication now quite a bit. YOu know GPS relies on satellites. there are things that we can do to mitigate the damage, but how long it takes to get it back depends on how powerful it is and what we've done in the interim to make sure that we're prepared.

BROOKE: The History Channel documentary also suggested that solar flares are as difficult to predict as hurricanes.

WALKOWICZ: I would say that this probably to predict hurricanes than it is to predict solar flares. We have what we call a solar cycle. Every 22 years essentially the sun goes through a very active phrase where it has lots of sun spots, lots of solar flares, over the following 11 years, it goes into what we call a solar minimum where it might still have flares occasionally, it might occasionally have spots, but essentially all's quiet on the western front. So now we're actually going into a solar minimum where it will be less likely that there will be flares although there won't be zero. And we do actually devote a fair amount of research resources to try to predict those. What we can do is be prepared to the extent that we can be prepared. But you know I used to live in California and i didn't spend every day worrying about whether there was going to be an earthquake. I just made sure that I had batteries, a flashlight, and fresh water.

BROOKE: But do we have the equivalent of those things, in terms of generating power through bicycle wheels, and the sort of thing that wouldn't require the sun - sticking an electrode into a potato.

WALKOWICZ: Yeah, I think you're going to need a lot bikes and a lot of potatoes.

[both laugh]

Maybe we should just make sure the power grid doesn't go down. [Laughs]

BROOKE: Lucianne, thank you very much.

WALKOWICZ: Thank you! It's been a pleasure.

BROOKE: Lucianne Walkowicz is an astronomer at the Adler Planetarium in Chicago.