Seymour Hersh Looks Back

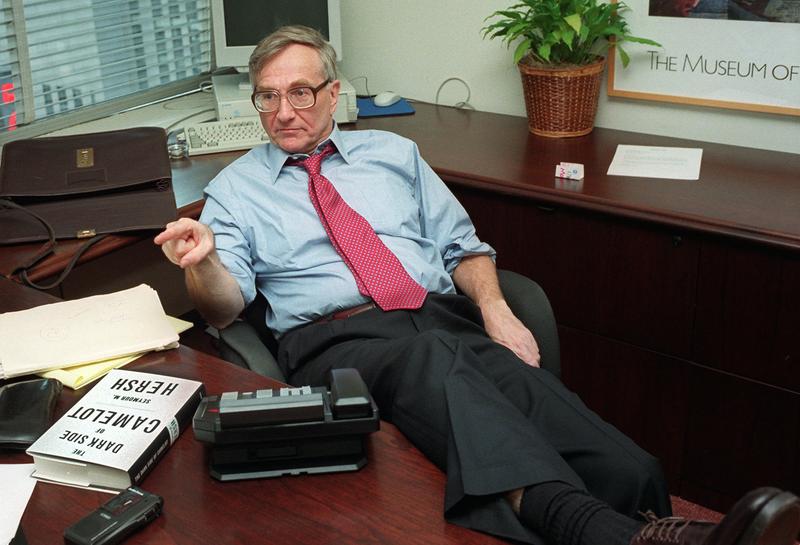

( Michael Schmelling/Associated Press / AP Images )

BOB GARFIELD: This is On the Media. I’m Bob Garfield.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And I'm Brooke Gladstone. Just a heads up, there are ethnic slurs, quotes from a policeman and a president, in the next segment.

Seymour Hersh is famous for consequential scoops, from exposing the massacre of Vietnamese civilians in Mi Lai, to CIA surveillance, to the torture of Iraqis in Abu Ghraib. Most recently, he's the author of Reporter: A Memoir. He’s also a twin and once, when asked by the parent of twins what it's like to be one, he replied, “It’s great. I won!”

SEYMOUR HERSH: [LAUGHING] I have twin sisters too. He’s a physicist from UC California but I, he’s got a specialty in wave theory.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm.

SEYMOUR HERSH: And here’s the story about America. There was a program called -- you got a second?

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Sure!

SEYMOUR HERSH: -- Deep Sea Submergence program. It was run out of Hawaii undercover. It was one of the biggest secret programs in the government. People who knew wave theory, noise underwater, my brother’s expertise, would monitor Russian submarines. So a new submarine would come out and we’d pick up the sound of the engine and there were people that would translate this to know where every Russian submarine, particularly the boomers, the ones with nuclear weapons, were at any time. My brother was brought into that program to help ‘em. And in the ‘70s, when he got in, I was writing about the program and exposing all the stupid things [LAUGHS] they were doing.

[BROOKE LAUGHING]

And he said, about 1990 or so, you know, he said, I was in a very secret program.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And you didn’t know your brother was in it.

SEYMOUR HERSH: No, no, he didn’t tell me because it was very top secret.

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

He said, you have no idea the trouble you caused me. Every year I had to take a lie detector test. When it was all over, the guy said to me, you know, your brother’s a real [BLEEP]hole. [LAUGHS] And I thought to myself, what a nice story about America.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: It is!

SEYMOUR HERSH: They didn’t ever suspect him of talking to me.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: As you described in the memoir, he was the one who was allowed to go off and pursue the sciences until he graduated. You were going to take care of your mom. Your father had died, took over your father’s dry cleaning business. Then you worked in a liquor store. You did a bit of flailing around. But there was an intervention.

SEYMOUR HERSH: What happened was back in the 1950s in high school, in my third year my father got cancer. My father had a business, a ghetto business, laundry and cleaning, a small shop that kept the family going. My parents were both Eastern European, didn’t talk much. There was not much communications. I had had some test that I took in the beginning of my fourth year and there were three of us who did well and one went to Harvard, and I think they both ended up there. And I went nowhere. I barely could graduate. I was just running my father's business and being horribly depressed. My father was dying.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm.

SEYMOUR HERSH: And so, there’s a local two-year junior college in Chicago that was run by the University of Illinois. Guys came back from the war and they were working and they wanted to be educated but they couldn't afford to go to the main campus in Champaign-Urbana 150 miles away. So they set up a two-year program, a junior college, in an old Navy barracks that they had built into Lake Michigan. I went to school there.

And I go to this class and I wrote a paper, and the guy who was teaching had just gotten his doctorate at Chicago, turned in the paper and a week later at the end of class he said, is Seymour Hersh here? So I walked up, thinking, like, 99% of the kids in the world, what had I done wrong, and he said, what are you doing here? And I began to mumble something, my father got sick, blah-blah-blah. And I was 18.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm.

SEYMOUR HERSH: He said, meet me at the University of Chicago admissions office in two days, and I did. And the next I know, I, I go -- I’m going to this wonderful university. What makes it, to me, very emotional is I forgot all that. I go on with life. I get to be a -- I get to -- I --

BROOKE GLADSTONE: You get to be a big deal.

SEYMOUR HERSH: I get to be a big deal. In 1983, I write a book about Kissinger, and my wife was going through mail and she opens this letter, it was from the professor. And it began by saying, you probably don’t remember me but I’ve intervened twice in all my years of teaching and one of them became a neurosurgeon and [LAUGHS] the other one was you. And I began to cry, ‘cause I suddenly remembered that moment, what are you doing here? And it happened again and again in my career. People saw things in me early on that I didn’t think I -- had.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And your first stop in journalism, City News, the place that you say Ben Hecht based “The Front Page” on?

SEYMOUR HERSH: Right.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: You said you were smitten but you observed that, and I quote you, “the ambitious young reporters working the courthouses and the police beats understood their mission was to live within the system and somehow make the city work.” That’s -- awful.

SEYMOUR HERSH: It was tyranny. It was a police and mob tyranny. I came there as a copy boy but I was clearly smart and interesting to some of the editors. I was a little mouthy too but so what? They, they got me to the street. I got in the Central Police and, you have to understand, I’m suddenly free. [LAUGHS] I suddenly am not running this dinky store that was crazy. You know, I was on my own. I could actually do something. This job saved me. I fell into it.

But after being a cop reporter for about three or four months, there was a killing in the middle of the night and two cops radioed in that somebody had tried to escape and they had to shoot him. And I was in Central Police overnight. Most of the time, it was quiet and we smoked the dope the cops had but sometimes you had a lot of action. And there was the killing of -- a, a cop had shot somebody, so I wanted to see the guys when they drove in to the parking lot. And so, I get down as, just as these two beefy red typical Chicago cops pull in, and one of their other buddies says, hey, [unintelligible], that guy tried to escape and you had to shoot him. He said, naw, he said, I told the [BLEEP]ger to run and I shot him. I heard it.

And so, I called my editor, I can’t believe what I just heard and I’ve got the license number. He said, don’t touch it. And I said, what are you talking about? He said, it’s your word against theirs. You’re gonna have to be off that beat [LAUGHS] if you do that and you may have to leave the, leave the reporting business. So I went a couple of days later and I looked up the coroner’s report, sure enough, three bullets in the back. And I tried again to go pursue the story. The editor said, you don’t understand, [LAUGHS] you’re not gonna do that story.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: What lesson did you take from that?

SEYMOUR HERSH: Oh, a big lesson, that the business I adored so much was full of self-censorship and compromise, and so was I. And it made me hate self-censorship.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: We’ve previously discussed Mi Lai at length and we’ll link to that interview again, but you told us that when you went after that story, which was about the massacre by US troops of every last man, woman and child in a North Vietnamese village, in this case, how much were you pushed by a thirst for justice and how much by hunger for a blockbuster scoop?

SEYMOUR HERSH: I didn't know what I was getting into until I began to get into it. I didn't realize how, how grotesque it was, GIs going into a village of 500 people or more, thinking there might be an enemy there, seeing no enemy, just going and killing everybody, thinking that’s the orders, throwing babies in the air and catching them on bayonets. During the killing, as we all know, they stopped and ate their lunch by the ditch in which they’d shot people. I didn’t -- none of that was known to me.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Yeah.

SEYMOUR HERSH: Of course, the thought I had when I began to get close to the story and found Calley and found his lawyer, I had two muddled thoughts. One was fame, fortune and glory. And the other one is that, God, maybe we can do something to stop this war.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: When you were working in Washington which, in many ways, was a fraught period, there were early episodes that opened your eyes to the fact that people will lie bald-faced.

SEYMOUR HERSH: One of the things that happened with the Pentagon, it was very hard to report on the Vietnam War because

you had to sign in at every office you went to. So if you got something really good from somebody, you had to spend two days talking to other generals and --

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Just to muddy the waters.

SEYMOUR HERSH: -- make it harder for them. If there were more than five or six people, they wouldn’t search you out. [LAUGHS] And so, Harrison Salisbury of the New York Times had gone to Hanoi, the first reporter allowed in in years, in 1966, and over Christmas of ’65-’66, and he was filing dispatches to the Times that talked about bombing that we didn’t know anything about, bombing the hell out of the North and a lot of bombs missing their target.

I was writing propaganda, as the AP correspondent, and over Christmas there was a little incident --

[BOTH SPEAK/OVERLAP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: You were writing propaganda.

SEYMOUR HERSH: Well, of course. I was getting the briefings.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Did you know you were writing propaganda?

SEYMOUR HERSH: I don’t know what you think Pentagon correspondents do for a living --

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

-- but I will tell you that, inevitably, if you’re covering a beat and it involves the Pentagon or the CIA, you’re writing propaganda. But I wrote some very aggressive stuff. And over Christmas, there was a, a cocktail party for the press and everybody was being nice. And McNamara had been lying about bombing. I had gotten to some admirals and generals who were telling me the truth. And so, I broke the rules. I said, tell me about the bombing, Mr. Secretary. He had worked on a study of the bombing after World War II, a special commission. He was an officer and he wrote papers that talked about how bad

the bombing was. And he laughed and he said, yes, it’s true, bombings never go where they go, and everybody laughed. And I was enraged.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: This is at a cocktail party.

SEYMOUR HERSH: Well, that was off the record, so I wrote a piece about it under a pseudonym for the, for a very gutsy weekly, the National Catholic Reporter that was a brilliant paper.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm.

SEYMOUR HERSH: [LAUGHS] I wrote a piece about McNamara with his arrogance, and they put it all over Page 1. You know, I was a marked man, and deservedly so. I broke the rules.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: You wrote that when Robert McNamara’s senior press aide retired in 1967, he spent six years screaming at reporters who got out of line, a guy named Arthur --

SEYMOUR HERSH: Silvestre.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: -- Silvestre.

SEYMOUR HERSH: Right.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: He wrote this, it’s on page 62: For six years, I watched cover stories, promulgated by his own office, go down as smooth as cream when I thought they would cause a frightful gargle. In other words, he had contempt for the press corps for swallowing the garbage that he was dishing out day by day.

SEYMOUR HERSH: It’s, it’s an amazing clip. You know, one of the things about doing a memoir is you fre -- well, you think your memory is good and the first thing you learn is it’s terrible, and that was an essay in The Saturday Evening Post or something.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: It’s a devastating indictment.

SEYMOUR HERSH: I -- that’s what I thought but the coverage of the war from the -- from Washington was awful.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm.

SEYMOUR HERSH: It was terrible. And when I got hired by the New York Times it was by Abe Rosenthal with whom I’d tangled so much. [LAUGHS]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: The story in the book about that relationship.

SEYMOUR HERSH: Oh my! [LAUGHS]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: You had legendary scoops at the time about CIA surveillance, about Watergate. You always got space on the front page, well, almost every time. And there is an incredible story about you waking up the Times managing editor, Abe Rosenthal --

[BOTH SPEAK/OVERLAP]

SEYMOUR HERSH: Oh, no my --

BROOKE GLADSTONE: -- in the wee small hours, under very awkward circumstances.

SEYMOUR HERSH: You know, despite my fighting with Abe, and it was constant, he did trust me. So they hired me to, to go to Washington and, and do stuff on the war. And I learned in early 1972 there was some horrible secret inside the CIA involving criminal activity in America. There was a substantive study done by the CIA itself all full of stuff about how they were watching me for two years. I hadn’t told anybody about the domestic spying story. I knew there was something there. It took a long time.

Finally, December the 20th, 1974 I see the head of the CIA, William, Colby, in his office about 9:30 in the morning and I say, okay, you wiretapped this guy and you did this and you did -- all these operations domestically. And what Colby did is he never said no. He would say, no, no, we didn’t do 150 wiretaps of reporters, we only did about 30. And I think he thought that was okay but I knew he was in trouble. I could do this story.

And this is a story, actually, about a reporter and, and an editor. I called Abe up from a pay phone on Route 123 outside of the CIA and said that the CIA has been spying on American citizens. He said, what? I said, yeah. He said, well, go write it. And so, I went to the office and I stated writing. Abe had told the Sunday editor, a guy by the name of Evan Jenkins, that Hersh is going to have a story. So they saved 2500 words, I guess.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm.

SEYMOUR HERSH: About 2 o’clock or 2:30 in the morning, I’m in the office, I’m alone. I love being alone at night in a big newsroom.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And you were about at word 7,000 at that point.

[BOTH SPEAK/OVERLAP]

SEYMOUR HERSH: I was at word five but it was going to go that much.

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

It was going to be a whole page. The guy making up the Sunday paper, Jenkins, says, what are you doing, Sy? I said, what do you mean? He said, well, you’ve written 4 or 5,000 words. Abe told me about two or three columns. The paper’s all made up, we know you’re doing a story, we’ve got space on it on Page 1. Maybe I can get another 500 words for you. I said, what? I said, okay, hang up. I, I don’t socialize with editors. [LAUGHS] I just don’t, never did and I don’t like to. I mean, they’re, they’re nice people, you know, but, you know, I’d rather have a rabbit as a friend.

[BROOKE LAUGHING]

Anyway, in the editor’s desk I found a home phone number for Abe and it rings about seven, eight times.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: ‘Cause this is 2:30 in the morning.

SEYMOUR HERSH: Yeah. So what? Somebody wrote a review and he said, he’s so self-obsessed. Are you kidding? [LAUGHS] I’ve got a story about domestic spying. What do --

[BOTH SPEAK/OVERLAP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: I’m just saying, that’s why it rang so long.

SEYMOUR HERSH: And so [LAUGHS], at the time his wife’s name was Ann. I’d met her once. I said, Ann, this, blah-blah-blah-blah-blah, you got to wake him up. She said, what? I, I said, Ann, I got to wake him up. She said, well, go find his -- the unpleasant words you said about the woman he’s sleeping with and hung up. [LAUGHS] And I said [ ? ][LAUGHS], oh my God, I’m in the middle of a soap opera. But I called back [LAUGHS] and she answered on the third, what, she said. I said, tell me who the lady is, I got to find Abe. It’s about a story that you’ll be glad you helped.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: [LAUGHS]

SEYMOUR HERSH: Long silence and she gave me the name. It was somebody who was in public life who wasn’t listed. [LAUGHS] I then had to call one of my agents up and get them to get an unlisted phone number, and I then called her [LAUGHING] and --

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So now it’s about 3 in the morning. [LAUGHS]

SEYMOUR HERSH: Yeah, well, and so --

BROOKE GLADSTONE: I can’t believe you called back Ann Rosenthal but go on.

[BOTH SPEAK/OVERLAP]

SEYMOUR HERSH: I called back and I said, you’ve been a reporter’s wife for 25 years, you know the business. I need him. There’s a story that’s important about laundering by the government and I know you’d want the story to be published. And so, she helped me. And so, I found the -- this person and I -- and I called and had one of those cut-offs after five rings.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm?

SEYMOUR HERSH: I called again and finally [LAUGHS] she answered. And I said, look lady, just wake him up. I beg your pardon. I said, just tell him, Sy Hersh is on the phone and I’m gonna go blow up the fu[BLEEP]’n news. A minute later he says, are you crazy? And I go, blah-blah-blah-blah-blah-blah, blah-blah-blah-blah [LAUGHS] and he says, hang up, I’ll call you back in five minutes. So I hung up. And I’m running around, pacing, jumping up and down. Five minutes later he calls and he says, okay, whatever he called me, numbskull or whatever it was [LAUGHS], here’s what’s gonna happen: 1.6 million editions of the New York Times tomorrow is gonna have a house ad on one side and your cockamamie -- I remember that word -- story on the other side.

[BROOKE LAUGHING]

You happy? I said, yes. Now, if you --

[LAUGHTER]

-- ever tell anything about what happened tonight, he said, I will come and beat the hell -- whatever he said. And I waited ‘til he died, he’d been dead for 10 years and wrote it [LAUGHS] and thought, what the hell?

But here’s what’s important. It’s a 7,000-word story burying the CIA, more, 7500 words, stayed writing to about 7, then at 12 they had an edit. There was concern about the word -- I used the word “massive” and we agreed that there was 100,000 files I knew about -- that’s massive -- on American citizens. The sourcing was A plus.

Anyway, the New York Times ran a story burying the CIA. It led to the Church Hearing, it led to the first formal investigation, it led to the es -- establishment of the House and Senate Intelligence Committee. which has been ruined now by

partisanship --

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm.

SEYMOUR HERSH: -- but led to incredibly good change.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm.

SEYMOUR HERSH: They ran that story and it was a t -- sole matter of trust between Abe Rosenthal and me. I did that story and that you didn’t know about it for two days in advance, even though the CIA had known about it for two years, and it didn’t matter. The trust was there.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: But let’s talk about when and how that happens, ‘cause what I gathered from your book is that it was much easier to expose the wrongdoing of public institutions than of powerful people who are close to reporters. And Bill Kovach, a colleague of yours in ’73 who went on to become the Washington bureau chief, explained years later to the Washington Post that one of the biggest problems he had as an editor was, quote, “managing Sy at a newspaper that hated to be beaten but didn't really want to be first.” So you’ve got the CIA surveillance story out but, evidently, frequently, it played out differently. SEYMOUR HERSH: Yes, well later it did at the New York Times. What happened is later I picked up a freelance writer named Jeff Gerth who was a wonderful journalist who had a great career at the Times. I was doing stuff on organized crime. I was living in New York then, and I went after a big corporation --

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm.

SEYMOUR HERSH: -- Gulf & Western, run by a guy named Charlie Bluhdorn, who was a very good friend, apparently, of the publisher. He, he owned Paramount Movies and he used to show movies in advance to all the editors and all the powerful people in town. The New York Times just did not want to take on big business. They were squeezed by me. To their credit, they ran four stories that I and Jeff did on Page 1 about Gulf & Western but --

BROOKE GLADSTONE: The editing, they were denuded of all style, of all anonymous quotes.

SEYMOUR HERSH: Yeah, it was, it was the worst experience I had. The hardest reporting in the world is to do a corporation because it turned out later, as I did this book, when -- in doing the research, the New York Public Library has all of Rosenthal's papers, and there was all these letters that Gulf & Western had written about me and what I and Gerth were doing and saying.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: To discredit you.

SEYMOUR HERSH: But they never showed ‘em to me.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Yeah.

SEYMOUR HERSH: The editors never gave me a chance to answer that. I don't know what they believed or didn’t believe. And I left and went on to write books. But it was a terrible time. It was a year of purgatory. The stories were so beaten down, they were incomprehensible, I thought.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: You know, it's funny, despite all the sturm und drang you went through in Washington, even before you got to New York, you told Bob Thompson of the Washington Post that those years in Washington, there’ll never be a period like that in our business again. Nobody can understand what it was like. Boy wake up, boy hears story, boy gets story, boy puts story in paper, no trauma.

SEYMOUR HERSH: I said something else I decided not to put in the book. [LAUGHS]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: What was that? [LAUGHING]

SEYMOUR HERSH: It was over at Gulf & Western or even the Korshak -- I did a series of the gangster called “Korshak” -- boy wake up, boy gets story, boy get edited, boy get tortured, boy throw typewriter through window.

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

Boy go home, boy come back. Window fixed, typewriter back at his desk, nobody says anything, [LAUGHING]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: [LAUGHS] And that’s true!

SEYMOUR HERSH: It was awful.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: [LAUGHS] There are many lessons here for journalists or would-be journalists but there was something I found really illuminating when you were describing what you called “the Wicker moment” and then the moment that you had that revealed the character of powerful people.

SEYMOUR HERSH: [PAUSE] Well, Tom Wicker was this wonderful, wonderful journalist, and in ‘73 or ’74, I was pounding away like everybody else, and so, I received the transcript. At that time, Nixon transcripts were not made public but they were using the White House taping system, and once the government learned about it they used it to prosecute people.

I got a transcript of Nixon just using every vile term he could for minorities, Italians and Polish people and Jewish people, in particular. So we told the White House in advance we were going to write this story about using terms like “spic” and “kike.” There was a lot of angst about it.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm.

SEYMOUR HERSH: The White House, the press apparatus, there was a lot of attacks on me and the Times. The whole context of what it had raised, just serious questions about this president’s -- who in the hell is he? What kind of a person is he --

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm.

SEYMOUR HERSH: -- to talk this way in private? And so, while this was going on and it was back and forth, Tom Wicker, who was then the columnist, and remember, when I was at the Times, Tony Lewis was a columnist, so you had Russell Baker using fey sardonic language to make wonderful points --

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm.

SEYMOUR HERSH: -- instead of this constant drumbeat we have, that, you know, of “Trump’s so dumb, Trump’s so dumb.” But we had Tom Wicker writing great columns.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm.

SEYMOUR HERSH: Anyway, he stood up next to me and he said, I want to tell you a story that’s been tormenting me. In ’65, when Johnson began to expand the war in Vietnam, every Friday they were -- in the summer, they’d fly down to the ranch, you know, in Texas, this huge ranch that he had. And one Friday before he left, he filed a story raising a lot of questions about the conduct of the war. In those days, the Times would fly the Saturday newspaper down to the ranch, and so, in the morning everybody saw the story. And Tom's column was fronted. It was on Page 1. And there was a morning briefing they had around 10:30. George Reedy was the press secretary then, I think. He would say to everybody that the lid is on, which meant go play some golf or go play tennis.

[BOTH SPEAK/OVERLAP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm, no news will be made today.

SEYMOUR HERSH: No news. Johnson had a little white Cadillac convertible and, all of a sudden, here comes the Lincoln convertible at high speed, blowing dirt all over on a dirt road, slams on the, the brakes right in front of the, the press group, opens the passenger door, calls out, “Wicker” and Wicker looks at him and he crooks his finger. So Wicker walks and he gets into the car. Johnson says nothing. They drive off for -- you know, at 50, 60 miles an hour, and he stops by some bushes and puts on the emergency brake, walks behind some bushes and bends down and defecates -- Tom can see this -- wipes himself with leaves, comes back, gets in the car, turns around, doesn’t say a word, speeds like hell back to where the press is still there sort of wondering what’s going on, stops, leans over, open the door, give a little motion, get out.

Tom said, here, Sy, here’s why I’m talking to you. I knew then in this visceral way that the war was gonna continue no matter what and that he was gonna kill a lot more people, that he was crazy when it came to that war. And he said, I didn’t know whether to tell that story or not and I never did. So I’m glad you wrote the story about what Nixon said about Jews and Italians -- “wops” and “kikes” and “polacks” -- I’m glad you did that. That was his message.

We already were building up the war. We had 300,000 people but the real casualties didn’t come -- there were 2,000 a week and by ’67, ’68 -- in ’68, there were some months where we had 10,000 a month killed. But the underlying message to me that left me chilled was he knew something then, viscerally.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm. [AFFIRMATIVE]

SEYMOUR HERSH: It must have haunted him.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Well, you see, that’s just it. Nixon, in employing that language, his office said, oh well, it was affectionate, it was a joke, but it was crazy. And what Johnson did -- was crazy!

SEYMOUR HERSH: Yes.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And, and let’s talk about Trump, just briefly. A great deal of ink has been spilled over his administration's treatment of the media, specifically the lies, whether the press does enough to push back. Do we see an endless stream of Wicker moments or is this something else?

SEYMOUR HERSH: One thing you can say is what you see is what you’ve got. You’re not going to find private tapes in which he says something differently.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm. [AFFIRMATIVE]

SEYMOUR HERSH: My worry about what's going on is I watch the polls. He’s gone up maybe seven, eight points, that’s 20 percent, since the beating up got more intense.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: The press beating up on him.

[BOTH SPEAK/OVERLAP]

SEYMOUR HERSH: Yeah, and I don’t know if he’s maybe smarter than we think. He’s controlling the agenda totally, totally! The attacks now and “the FBI’s out to get me,” whatever it is, it just doesn’t end the coverage. I look at the cable news and I just think, oh, have we really come to this, that if I’m in the New York Times I get a tip on a story, a tip becomes a story and then I put it online for the Times and then I go on, you know, MSNBC that night to talk about it?

I can’t relate to what’s going on. A lot of tips and a lot of secondhand stuff is being run as serious stories, even in the good newspapers, and that’s demeaning. If Putin says, I want to see you, he may go see Putin. What are you going to do, attack him on that forever? What if he takes out 28,000 troops from, from South Korea, if we have that many, or 26,000 and saves us a couple of billion dollars a year, is that bad? He may be a circuit breaker. I’m just saying, pick your fights, that’s all.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm.

SEYMOUR HERSH: Giuliani ranting and raving should be ignored.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm. [AFFIRMATIVE]

SEYMOUR HERSH: I wouldn’t pay much attention to that. I wouldn’t pay much attention to the daily-daily. [?] I would go all over every Cabinet member. The Times and Post are doing Pruitt. I would do ‘em all. I would do over decisions made. I would do over how things work, a daily story about some child taken away from his mother on the Mexican border.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm.

SEYMOUR HERSH: I would just do that. It’s so freakin’ insane. I would talk to experts who would tell you how horrible that’s gonna be. You’re creating monsters when you do that and how damaged, that’s just incomprehensible.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm. [AFFIRMATIVE]

SEYMOUR HERSH: Okay, you got my lecture, more than you want.

[BOTH SPEAK/OVERLAP]

Goodbye, I got to go!

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Okay. Bye! Thank you very much.

SEYMOUR HERSH: Goodbye!

BROOKE GLADSTONE: After 90 minutes, he -- ran away. Seymour Hersh is the author of Reporter: A Memoir. In the next few days, you’ll be able to hear a longer version of our talk at onthemedia.org.

BOB GARFIELD: That’s it for this week’s show. On the Media is produced by Alana Casanova-Burgess, Jesse Brenneman, Micah Loewinger and Leah Feder. We had more help from Meg Harney. And our show was edited -- by Brooke.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Katya Rogers is our executive producer. On the Media is a production of WNYC Studios. I’m Brooke Gladstone.

BOB GARFIELD: And I’m Bob Garfield.

* [FUNDING CREDITS] *