Separate and Unequal

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

BOB GARFIELD: This is On The Media, I'm Bob Garfield. History may indeed be written by the victors but the victors don't necessarily script the future. After the Civil War, The triumphant North imposed reconstruction–essentially an occupation government in the south. The result was an ugly backlash in Southern states including the incremental imposition of Jim Crow laws on the very black Americans supposedly emancipated in the midst of war. Nineteenth century civil rights activists battled Jim Crow, eventually, to the Supreme Court. That case was Plessy versus Ferguson. And in 1896 the court's decision marched the nation backwards. Despite three post war amendments granting blacks equal rights, racial segregation was permitted on a separate but equal basis. With one lonely dissent, Plessy became the law of the land for six decades until effectively reversed in 1954’s Brown v. Board of Education. Steve Luxenberg is an associate editor at The Washington Post and author of Separate: The story of Plessy V. Ferguson and America's Journey From Slavery to Segregation. Steve, welcome to OTM.

STEVE LUXENBERG: Hey thanks Bob. Glad to be here.

BOB GARFIELD: The term separate but equal never actually appeared in the decision. But the case, and your book, hinge on that idea because in Louisiana, as would be the case throughout the South as Jim Crow evolved, railroads were permitted to divide the races in separate cars.

STEVE LUXENBERG: And this is the reaction in part to reconstruction and the three Reconstruction Amendments that expand equal rights, provide citizenship for blacks, ensure equal protection, voting rights. There is a resistance to that among whites in the south who have lost political power, lost economic power. Separate but equal does not appear in the decision as you pointed out. It does appear in the dissent, but it becomes the phrase that the Supreme Court uses in 1954 in the Brown decision and that's how we regard the shorthand today.

BOB GARFIELD: Now to the particulars of the case, the plaintiff Homer Plessy wasn't some random victim of segregation. Like Rosa Parks, nearly a century later he was handpicked for the role and the circumstances were engineered for an arrest.

STEVE LUXENBERG: Well, they were trying to create the Plessy team down in New Orleans which is where the case comes from. It is an unusual city–every shade of the spectrum under the sun is there. And the group that brings it is a group of mixed race, French speaking, often, Creoles–that means native born. Frustrated after more than a century of trying to get their rights, most of them have never been enslaved. Their parents weren't enslaved. Their grandparents weren't enslaved. And they feel that their best argument is to throw some confusion at the court in part. Plessy is fair skinned enough to pass for white or to cause that confusion, and so they want to be able to argue that the law is unenforceable. It doesn't define white, it doesn't define mixed race, and so therefore how can you possibly enforce this law when many people riding the trains in Louisiana are of indeterminate race.

BOB GARFIELD: The case was the culmination of decades of activism and legislation.

STEVE LUXENBERG: The first of those cases is in 1841 in Massachusetts when a slightly built black New York abolitionists named David Ruggles decides to bring an assault charge against the conductor who tries to separate him on a Massachusetts railroad. And he loses but he establishes a very important principle which is that we can go into court to pursue our grievances. 1892, they know they're probably going to lose and yet this is a group of fighters and they're not going to sit by and take it without bringing in their case.

BOB GARFIELD: Well there's no need to withhold the ending of this story. That decision was catastrophic for blacks and for American society as a whole–an utter repudiation of civil rights and an assault on the basic humanity of African-Americans.

STEVE LUXENBERG: And opening the door to other statutes, other states enacting separation laws to separate waiting rooms, separate bathrooms, separate water fountains. All of this was anticipated by the only dissenter in the case, John Marshall Harlan of Kentucky, a Southerner from a slave holding a family. And he says this is what's going to happen. He doesn't predict those specific conditions but he does talk about separate juries or separate courthouses, and he says this day will one day be regarded as shameful as Dred Scott. That's the ruling before the Civil War that blacks free or not could not be citizens.

BOB GARFIELD: Now this was the 19th century, newspapers were wholly aligned and allied with political parties, the Whigs, the Know-Nothings, the Democrats, the Republicans–and by the way Democrats and the Republicans kind of flip flop from how we know them today. The legality of slavery, the path to war, the terms of reconstruction, they were all litigated by a highly partisan press. No?

STEVE LUXENBERG: Absolutely. That's why you have newspapers remaining today that are called the Springfield Republican or the Arkansas Democrat. This is where they began as alliances with political parties. And nobody thought that was very unusual. Reporting, in the early part of the century and through probably 1880 or 90, was almost non-existent. It was frustrating for me as a researcher to be reading these newspaper accounts and they have a lot of opinions and hot air, but they don't have a lot of facts.

BOB GARFIELD: A pre-fact society.

STEVE LUXENBERG: It wasn't fake news, it was pre-news.

BOB GARFIELD: Facts are no facts, it is shocking how vituperative, how nakedly racist the Democratic press was–particularly in the south.

STEVE LUXENBERG: Well, white superiority, as opposed to white supremacy which is also a part of this century, is rampant. And they reflected that in their newspaper articles, in their letters, in their conversation. White supremacy does come out of the loss of economic and political power after the Civil War which gives rise to the fear and anger that creates the Klu Klux Klan in 1867 in Tennessee and then it spreads to the other in southern states. And violence underpins this era from the 1970s all the way through the mid-20th century where lynching becomes a way to settle issues that whites feel that they've lost–the political power and the economic power. And the press reflects that.

BOB GARFIELD: To read the book because it focuses on contemporaneous coverage, you would think that race was like the number one trending story for 60 years. But after all of this foment, you know, to say the very least, by the time the ruling came in on Plessy, the press was kind of AWOL.The coverage of the decision that would have such brutal ramifications for society was barely even mentioned. Was it just race fatigue?

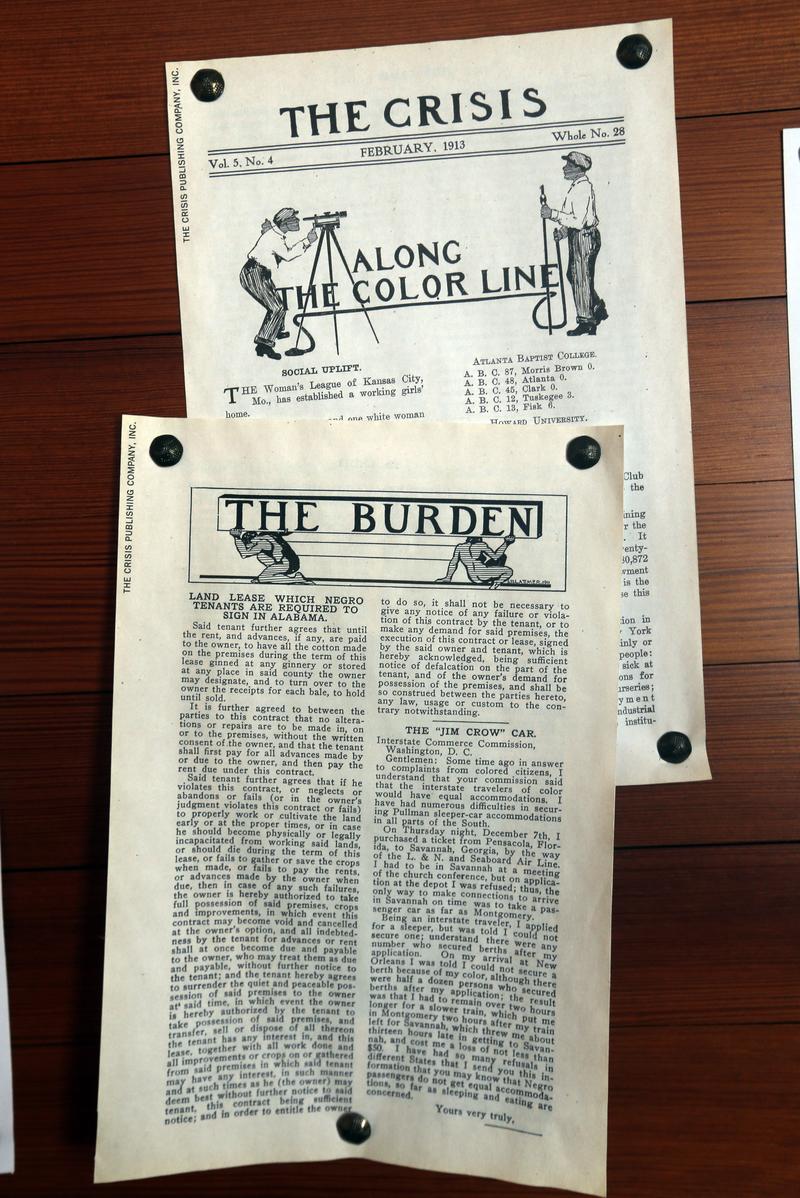

STEVE LUXENBERG: Well you're talking about the white press, remember. You use the term mainstream before. The white press saw this as an expected decision. When Tourgeé, the lawyer for Plessy showed up from western New York in Washington to give the oral argument, the Washington Post, my newspaper covered it with a column called Capital Chat. In which they said that Tourgeé, who had written a novel called Fool's Errand about reconstruction South, was on another fool's errand by trying to litigate this case that everybody knew was going to end with the Supreme Court ruling in favor of separation. They were right. So in terms of the way the press operates, 'what's the news here?' Well, there's not a lot of news so we're not going to give it great attention. But the Black press, on the other hand, I mean the Richmond Planet says that after this ruling 'evil days are indeed upon us.'

BOB GARFIELD: Albion Tourgeé, the lawyer and judge and novelist and newspaper columnist, was one of the heroes of your story. Another was the author of the sole dissenting opinion on Plessy, Justice John Marshall Harlan, known as The Great Dissenter. Here's one line from his dissent. 'Our Constitution is colorblind and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens. In respect of civil rights, all citizens are equal before the law. The humblest is the peer of the most powerful.' Marshall was from Kentucky, former slave owner, a former opponent of the reconstruction laws that he, at the time, deemed too punitive to the south. But obviously transformed. How?

STEVE LUXENBERG: Well, it's a remarkable transformation. A very hopeful one because it shows that somebody can hold despicable views and then abandon them. And he does so forthrightly. I don't have any doubt about the genuineness of his transformation. He was a proslavery candidate for Congress at the age of 25 in 1859. He comes from a slaveholding family. But he does raise a union regiment in 1861 because he believes that the union needs to be preserved both north and south. But he states that he's not going to fight a war against slavery. By the 1868 period, he has changed his mind–and partly it's politically driven. He has no home. He can't believe that he--he should belong to the Democratic Party which is filled with ex angry confederates who have lost the war to trying to accomplish by the ballot box what they couldn't accomplish by the war. And so he joins the Republican Party, that antislavery party, and he turns his eyes toward Washington. Because as a man who wants to make his mark in the world, an ambitious man, it's the only way that he can see that he's going to have a position that's going to give him some influence. And he fortunately is nominated to the court in 1877.

BOB GARFIELD: But Steve, I want to take note of that phrase in his dissent. Equal before the law. Neither Harlan nor any of the advocates, Black or white, who devoted their lives to equal rights are ever heard in your book espousing what was called social equality. The idea is that Blacks and whites would ever mingle.

STEVE LUXENBERG: Well, even Harlan in his dissent says that the White race is superior to the Black race and it will be for all time, as long as it continues to respect the idea that everyone is equal before the law. That's an odd way to go after equality, I think. But it reflects the attitudes of the time. And Tourgeé, in his arguments he has is quite inventive argument which is that your race is your property and if you could pass for white and white is a better economic position than to be black, how can you be prevented from trying to exploit that reputation and property and be denied it without due process. Now if you think about that it's a terrible argument because it means if they win that there could be a car or a railroad car with white and mixed race passengers but still a separate car for those people who can't pass for white. So I tried to wrestle with this. Why would they make that argument? And the answer, I think, is pretty obvious he wants to win and he sees these Supreme Court justices as men of privilege and class who regard property rights as paramount. And so he's given them a property right argument.

BOB GARFIELD: I mentioned that the press is an institution operated quite differently in the 1850’s than it does today. And a lot of the adequacy was basic crusading. It was constant coverage, beating the same drum over and over and over–sometimes for decades. As a modern journalist, did that make you feel at all queasy or did you kind of long for the days when a news organization would put all of its reputation behind an ideal?

STEVE LUXENBERG: I think I saw it in its own context as being different. I mean, you have a newspaper in Massachusetts, The Liberator, which is the arm of the abolition movement of the Massachusetts anti-slavery society. Every week it's hammering on the issues that matter to that organization. It's a storehouse of information about the times. It's not objective reporting, but I can handle that. I wouldn't want to necessarily work in that environment but, if I were living in the 1830s and 40s maybe I would have, who knows.

BOB GARFIELD: What do the media tend to miss, now, when we talk about Plessy v. Ferguson?

STEVE LUXENBERG: They often say that the Supreme Court has created the doctrine of separate but equal and made it the law of the land. Well, I would argue that it didn't create the doctrine. It's been afoot in the country for 60 years. Supreme Court is endorsing it. But more importantly, what we do when we say the Supreme Court created is we're kind of giving the rest of the country a pass. This is the shame of the North, the shame of the South, the shame of all of us. It's not proper to lay it only at the feet of the Supreme Court.

BOB GARFIELD: Steve, thank you very much.

STEVE LUXENBERG: Well thanks Bob.

BOB GARFIELD: Steve Luxenberg is an associate editor at The Washington Post--.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER].

BOB GARFIELD: --where, in the interest of full disclosure, he, for some number of years, edited my pieces.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

BOB GARFIELD: That's it for this week's show. On The Media produced by Alana Casanova-Burgess, Micah Loewinger, Leah Feder, Jon Hanrahan and Asthaa Chaturverdi. We had more help than Xandra Ellin. And our show was edited by Brooke. Our executive producer is Katya Rogers. Our technical director is Jennifer Munson. Our engineers this week were Sam Bair and Josh Han. On The Media is a production of WNYC Studios. Brooke will be back, you know, one of these days. I'm Bob Garfield.