The Self-Driving Car Sales Pitch

( Hans Tore Tangerud )

BROOKE GLADSTONE: This is On the Media, I'm Brooke Gladstone.

BOB GARFIELD:And I’m Bob Garfield.

[CLIP]

FEMALE CORRESPONDENT: Welcome to the future of grocery shopping. Food delivered to your doorstep in a self-driving cars.

MALE CORRESPONDENT: Barbara Adams just used her phone to summon the self-driving future.

MALE CORRESPONDENT: Toyota showed a concept vehicle earlier this year at CES that invasion a Pizza Hut delivering its pizzas to you fresh out the door maybe even being made in the vehicle.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

PETER NORTON: Autonomous Vehicle, developers, the tech companies and the carmakers are teaming up to sell us, again, a utopian future.

BOB GARFIELD: Peter Norton is a historian in the Department of Engineering and Society at the University of Virginia. As he surveys the media landscape, he's seeing a glimpse of one possible future and practically a scene for scene remake of the past. The salesmanship behind autonomous cars, he says, 'harkens to the earliest Detroit strategy of cultivating discontent with the mere status quo.' In 1929, auto tycoon Charles Kettering actually preached, quote, “Keep the consumer dissatisfied.” And consumer marketing has hated him ever after.

PETER NORTON:The transportation planning that predominates today arose during the era when public relations was being invented. And it was being invented because it was starting to look like people had all the stuff they wanted. So you had to convince people that they had needs they didn't know were needs like, say, bad breath.

[CLIP]

COMMERCIAL: Try Listerine, buy Listerine. Keep breath fresh and clean with Listerine!

PETER NORTON: You had to convince them that they needed shampoo, which they didn't use before and you had to convince people that they needed to be able to drive anywhere anytime without delay and have a free parking spot when they arrive.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

PETER NORTON: None of those needs were needs that began as demands from ordinary people. All of those needs were sold to people and they were sold with really amazing showmanship.

BOB GARFIELD: The GM sales pitch had perhaps its grandest moment in 1939. At the same time that liberal democracy itself seemed to be crumbling around the globe. The sprawling utopian Futurama exhibit demonstrated to world's fair visitors the promise of fancy new roads.

[CLIP]

MALE CORRESPONDENT: New horizons, roads meant to go places. [END CLIP]

PETER NORTON: The city of 1960, 20 years in the future was presented as a driving utopia where everybody could go everywhere by car without delay and park for free when they got there.

[CLIP]

MALE CORRESPONDENT: And now we see an enlarged section of 1960s express motorway. Along the edge of this beautiful precipice, traffic moves at unreduced rates of speed. On all the express city thoroughfares, the rights of way have been so rooted as to displace outmoded business sections and undesirable slum areas whenever possible. Men continually strive to replace the old with the new. [END CLIP]

BOB GARFIELD: Futurama wasn't intended to be a rigorous exercise in urban planning but it also made no attempt to even acknowledge negative ramifications of a future motor America. In other, words it was an ad, 35,000 square foot ad.

EMILY BADGER: They were selling us ideas about how our lives would be built around cars.

BOB GARFIELD: Emily Badger covers urban policy for the New York Times.

EMILY BADGER: And so it's not in their interest to think very hard about what the unintended consequences of that would be. You know, to think about congestion, to think about sprawl and consuming agriculture land to build excerpts, how these highways would lead to the economic decline of a lot of downtowns, these highways would need to be built somewhere–and in many cases we would choose to build them through minority communities and cities. You know, none of that was part of the Futurama vision.

[CLIP].

MALE CORRESPONDENT: Penetrating new horizons in this spirit of individual enterprise. In the great American way.

BOB GARFIELD: And did the USA ever buy in!

MALE CORRESPONDENT: Is that you in that beautiful car?

FEMALE CORRESPONDENT: Power steering.

FEMALE CORRESPONDENT: What are you trying to do to me, you crazy little car?

MALE CORRESPONDENT: Car [End CLIP]

BOB GARFIELD:Because American culture is car culture and it goes beyond our commutes or thrills or conspicuous consumption and our family road trips. In October, Ikea, as in the furniture chain published survey data showing that if 22,000 people polled about 45 percent quote go to their car outside of the home to have a private moment to themselves. Cars are our emblems, yes but also, after our bedrooms and bathrooms, our third favorite sanctuaries.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

BOB GARFIELD: That's sort of integration into American life suggests a sort of end of history. The immutability of the personal car, or cars, in America's driveways till kingdom come. Except, maybe not. Just as there was a lot of 20th century money riding on universal auto ownership, there are 21st century Silicon Valley fortunes on Futurama 2.0. The wide adoption of ride sharing and driverless cars. We cease to be drivers only passengers.

EMILY BADGER: You know what would the business model for a car service that takes you around look like. Does it look like in exchange for getting a ride to work you have to sit there and stare at ads? I don't know, I get in a car and I'm sort of having like a virtual shoe shopping experience on my commute and if I do opt to buy a pair of shoes then I no longer have to pay for the ride.

BOB GARFIELD: Transport fueled by the attention economy. Crazy. But if you wonder how can anyone even imagine that Americans will trade their wheels, their identities, their freedoms, for a free ride in a robot world, well that's just what Silicon Valley does. The tech industry tends toward indifference bordering on contempt for the status quo and all that preceded it. In a recent New Yorker piece pioneering autonomous vehicle engineer Anthony Levandowski was quoted as follows: 'The only thing that matters is the future. I don't even know why we study history. It's entertaining I guess, the dinosaurs and the Neanderthals and the industrial revolution and stuff like that but what already happened doesn't really matter. You don't need to know the history to build on what they made in technology. All that matters is tomorrow.'

PETER NORTON: Oh this is quite amazing quotation I hadn't heard this line before.

BOB GARFIELD: Historian Peter Norton.

PETER NORTON: I would wonder what he would think about George Santy and his famous statement that those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.

BOB GARFIELD: For instance, what does the portrait of the self-driving utopia being sold to the American consumer leave out? What does it fail to consider? Norton finds a cautionary historical tale from the industrial revolution in Britain circa 1865.

PETER NORTON: Their future as the world's superpower depended on coal. Most of the experts said, 'yes we are using a lot of coal but our steam engines get significantly more efficient every year and that means even though we're using a lot of machines and a lot of coal is being burned, we will never actually deplete the supply at least not within a matter of centuries.' Stanley Jevons was a logician, mathematician, economist, all around genius. And Jevons sat down and did the maths and he realized, actually the more efficient each engine gets, the more useful applications we find for steam engines. And therefore, even though for each unit of work will burn less coal, we are going to be doing more and more stuff with these steam engines and it will actually end up that we'll consume more not less coal every year and therefore will deplete our reserves of coal much more quickly.

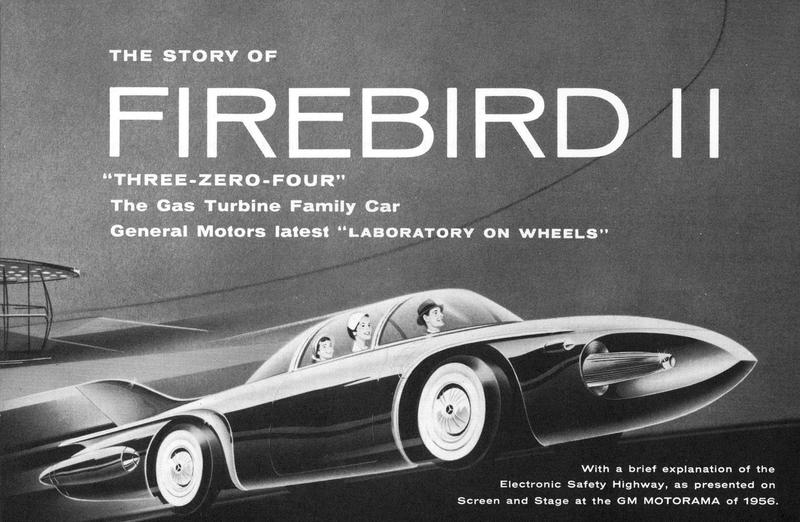

BOB GARFIELD: This paradox in which increased efficiency correlates with increased demand is a manifestation of what economists and planners call induced demand. The phenomenon that causes a new freeway often to increase not reduce traffic congestion. We heard some tape earlier from the 1939 World's Fair. Here's a relic from GM Motorama exhibit in 1956.

[CLIP OF MUSIC]

MOTORAMA: You got to slow down, slow down, so much traffic cuts the flow down. Till they bring the highways up to date, you can bet your high-compression we’re gonna be late. How sad, poor dad, too bad, we’re stuck, tough luck, yuck yuck.

BOB GARFIELD: Traffic, the solution to which of course was more highway. And gee whiz what do you know the future highways of the Motorama exhibit featured separate lanes for cars in a self-driving mode.

[CLIP].

MALE CORRESPONDENT: Here we go on the high speed safety lane.

MALE CORRESPONDENT: Well done Farber two. Your now under automatic control.

MALE CORRESPONDENT: Aw, this is the life. Safe, cool, comfortable. Mind if I smoke a cigar? [END CLIP]

BOB GARFIELD: Today the driverless industrial complex is sticking with the congestion free future story. But wait, there's more. A corollary narrative imagines a boon to cities, freed of dense downtown traffic and parking shortages. They convert the curbside to green space and livable cities thrive. Maybe or as Emily Badger suggests, maybe not.

EMILY BADGER: Well, there's also a scenario in which they make it possible for people to live even farther away. Now they're encouraging the consumption of even more rural land and turning it into whatever comes beyond ex-Siberia. But if those unintended consequences will happen they'll be totally predictable they're the same unintended consequences that happened when we built the interstate highway system.

BOB GARFIELD: Yes that's history but only the latest history. Sprawl did not begin with Dwight Eisenhower. Transportation technology has been expanding metropolis since ancient Rome.

EMILY BADGER: If you look at old cities that were built in a time when everyone got around by foot, you know, they're oftentimes about as far across as it would take someone to walk in like half an hour. And then we have the sort of subsequent innovations in transportation. You know, horse drawn carriages or street cars, the Model T, interstate highways–each of these innovations sort of radically changes what it means to commute.

BOB GARFIELD: And what it means to belong to a city. Just as streetcars turn the towns immediately surrounding American cities into so-called streetcar suburbs, superhighways flipped forests and farms into bedroom communities and edge cities. Habits changed, housing stock changed, society changed. But whether your home was in the city, a close in suburb or former orchard, there was one thing that never much changed–time.

EMILY BADGER: There is this sort of constant amount of time that we are willing to spend doing this activity.

BOB GARFIELD: This subconscious expectation was so universal that the Italian physicist Cesare Marchetti lent it his surname. Thirty minutes there and 30 minutes back became the Marchetti constant.

EMILY BADGER: And that remains constant whatever kind of community you're looking at. If you're looking at Mesa, Arizona where someone lives in the excerpts or if you're looking at Washington DC where I ride my bike almost exactly 30 minutes each way. I mean, in the American Community Survey from the Census Bureau the typical American spends like 26 minutes commuting one way. Obviously, there are people who commute higher than 30 minutes. But I do think that there's something true to the idea that there's a finite amount of this activity that we're willing to put up with.

BOB GARFIELD: So when new technologies allow us to cover more distance in the same amount of time and housing gets less costly with each outward mile and if self-driving cars do buy you an extra five or 10 minutes, how's that urban renaissance beginning to look. What if the autonomous future quite literally drives us still farther apart? Peter Norton's book Fighting Traffic documents the dawn of the motor age in the US including the years long battles over who had practical dominion on city streets. It was a decades long affair fought in courts, editorial pages and city halls that gave way to unequally divided thoroughfares. Pedestrians hear, cars here and here and here.

PETER NORTON: When automobiles began crowding city streets in the 19-teens and 20s, the sort of common sense response was, 'well we need to restrict the cars. They're getting in the way of the things that do move a lot of people like streetcars for example and they're also injuring and killing pedestrians.' Well, we restrict the cars, we slow them down. This was an impediment to people who wanted to sell more cars not less. And so they quite explicitly said, 'we have to change what people think streets are for. We have to change them from being for everyone, including people on foot,' to being almost exclusively for motor vehicles except, you know, at certain designated crossing points. One element of that strategy was to ridicule people who kept walking in the streets the way people had always done. They propagated this term jaywalking to ridicule those people.

[CLIP]

FEMALE CORRESPONDENT: I'd like to apologize for getting in your way this morning. I was practically jaywalking.

MALE CORRESPONDENT: No, no. You had a perfect right to be standing on the curb.

FEMALE CORRESPONDENT: But I was leaning over. [END CLIP]

BOB GARFIELD:A century later those echoes resound.

[CLIP]

MALE CORRESPONDENT: Uber has suspended all road testing of its self-driving cars after one of the SUV is hit and killed a woman in Tempe.

MALE CORRESPONDENT: Tempe Arizona police say 49 year old Elaine Herzberg was walking a bicycle across a busy thoroughfare frequented by pedestrians Sunday night. She was not in a crosswalk. [END CLIP]

PETER NORTON: The autonomous vehicle promoters began to explain to us what we need to do about this. One of them said we just need pedestrians to follow the rules and defer to automobiles more. I think what this well-intentioned statement signifies is the fact that we have forgotten how much we have compelled everyone to conform to systems that assume that driving is the best way for everyone to get around. When you don't know that history, you tend to think, 'well this built world around us is a reflection of what we wanted and a reflection of expert judgments.' In fact, if you look at the history you'll find that this world around us is the result of an effort to sell us and sell our governments on the notion that we have to rebuild our world for cars.

BOB GARFIELD: I have to push back here. Is it necessarily bad that, for example, pedestrians will have to learn to make accommodations for the benefits that self-driving cars or any other technological advancement may bring us. Isn't that part of the deal in the moving target that is society.

PETER NORTON: Ideally, technology offers us choices but I think what you'll find is that often technology takes away choices. If you could have a future where autonomous vehicles make it possible for you to choose to go by vehicle, by foot, by bike, by some other mode, well that sounds like a very attractive future to me and I have nothing to find fault with. But what I see in a lot of the visions of the autonomous vehicle future being packaged and sold to us now is a future where those choices, which are already meager, will get worse. Take for example the fact that if you're in an autonomous vehicle you can do your work you can play games watch a movie or sleep. Inevitably the distances between destinations start to grow. And this means that those people who might have preferred walkable distances, cycling distances or at the densities necessary for efficient and effective transit services, will gradually find that those alternatives get fewer and a kind of car dependency that we already are afflicted with gets worse. And I don't call that progress.

BOB GARFIELD: All right now obviously at this point I'm going to ask you about the Wizard of Oz.

[CLIP]

DOROTHY: Oh will you help me? Can you help me?

GLINDA THE GOOD WITCH: You don't need to be helped any longer, you've always had the power to you go back to Kansa.

DOROTHY: I have?

SCARECROW: Then why didn't you tell her before.

GLINDA THE GOOD WITCH: Because you wouldn't have been me. She had to learn it herself. [END CLIP]

BOB GARFIELD: So could you save us the whole yellow brick road deal and tell us what we know now and have within our grasp that will save us a bunch of dangerous but predictable errors in our transportation future?

PETER NORTON: In the book, the Emerald City is a fake. It's made out of white plaster and it looks like emeralds. Because you're required to wear green spectacles. And as you look through the green lenses this plaster city looks like an emerald city. It's a beautiful parable with many possible interpretations but one of them is that what we thought was so desirable turns out to be an illusion. When we make that realization, that might help us appreciate what we already have even what we once had but lost. Namely cities where if we want a cup of coffee we can walk two or three blocks instead of getting in a car and going through a drive thru. Why should we be buying this future and sacrificing a present that works imperfectly for the sake of a future we can't have.

BOB GARFIELD: Thing is it all looks so shiny and enticing and a little bit bizarre, surreal you might say like Oz minus the poppy fields. Because you don't need opioids to be lulled into a daydream. Sometimes all you need is too much imagination.

[CLIP: We're Off to See the Wizard]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Coming up, an operatic rendering of a titanic clash of visions for the city.

BOB GARFIELD:This is On the Media.