BOB GARFIELD: This is On the Media, I'm Bob Garfield.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And I'm Brooke Gladstone.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

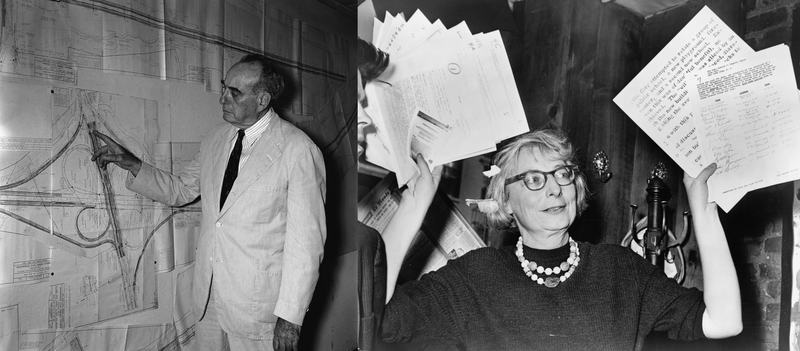

BROOKE GLADSTONE: You can talk about the highways of the past and the vehicles of the future, without considering the nature of a city. And you can't consider the effect of roads and cars upon cities without considering Robert Moses. He built local parks, state parks, beaches and super beaches. He also built glorious parkways, thundering expressways and tumbling interchanges all over New York City.

[CLIP] -- MONTAGE

MALE CORRESPONDENT: It is my privilege and pleasure to introduce to you, the man who literally needs no introduction, the Honorable Robert Moses.

ROBERT MOSES: The opening of a new modern urban highway carries this or that significance, according to the stance of the observer. Having from the beginning--

ROBERT MOSES: And now through traffic will move in a few minutes over steel and stone. It took us years of toil and sweat if not tears to build. We must eventually have three elevated expressways in lower and mid Manhattan and one in Harlem.

ROBERT MOSES: We are now at long last about work together to remove the obstacles in the way of healthy and interrupted progress. [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Robert Moses–virtuoso's civil servant, chronic overachiever, McCarthyist bully– earned himself many foes, most of whom found resistance futile during one crucial period. His relentless trajectory collided with that of local activist and self-taught architectural critic Jane Jacobs. By the 1960s, Jacobs had developed a keen sense for what made the city tick.

[CLIP]

JANE JACOBS: And I began to see that, to make it work properly and wherever it did work properly, there seemed to be an awful lot of diversity. Many different kinds of enterprises, many different kinds of people in small geographical area mutually supporting and supplementing each other. But You can't get such a feeling by wishful thinking. [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: It was a true urban legend. The titanic clash of visions for the city that still resonates today in community meetings.

[CLIP]

FEMALE CORRESPONDENT: So--.

MALE CORRESPONDENT: We all, we all except the Robert Moses photos us the situation--.

FEMALE CORRESPONDENT: Let me, let me finish. So-- [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: In popular culture.

[CLIP]

FEMALE CORRESPONDENT: What's going on?

FEMALE CORRESPONDENT: Janes speaking.

FEMALE CORRESPONDENT: Jane who?

FEMALE CORRESPONDENT: Jane Jacobs.

FEMALE CORRESPONDENT: Yes, who is Jane Jacobs?

FEMALE CORRESPONDENT: We've never heard of Jane Jacobs?

FEMALE CORRESPONDENT: No.

FEMALE CORRESPONDENT: Where have you been? [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And now Grand Opera, Judd Greenstein is hard at work completing an opera called A Marvelous Order about the clash between Jacobs and Moses.

JUDD GREENSTEIN: While most of the opera is about their conflict and there were really two conflicts. The first was when Moses wanted to drive Fifth Avenue through the heart of Washington Square Park. So he could extend it for real estate developing reasons. That's act one. And then act two, we get into the bigger broader struggle over LOMEX, the Lower Manhattan Expressway, which was going to run down Broom Street and completely destroy not just the character of Soho, Greenwich Village but also Jane Jacobs' neighborhood, Jane Jacobs' house. So act two we get personal.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Moses had a mix of things that were successful and not successful. The failures are notable and profound. Destroying the neighborhoods of the Bronx, failing to extend public transit to neighborhoods that desperately needed it–thus, creating a kind of apartheid in the city. This is also the city with one fifth of all the public housing in the entire country.

[CLIP: Opera]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Of course, the big problem is, if you have a big vision and you have big power, you create a nexus for corruption. And not necessarily financial corruption but corruption of spirit.

JUDD GREENSTEIN: Right. I mean, and the question is how do you let your personal views, how do you let your sense of ambition, your sense of yourself get in the way of what actually needs to be done for the people. I mean, he is really an idealist at heart and, you know, idealism can turn quite sour if you're marching down the wrong roads. And he really never got out of the 20s. I mean, his sense of what cars were and what highways meant to the city and all of his incredibly problematic personal tendencies bled over directly into his infrastructure building. At the same time, few people in human history have had such an impact on a city.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Some have observed that Robert Moses took a bird's eye view of the city, whereas Jane Jacobs' view was close up and, as you say, personal, really down on the ground.

JUDD GREENSTEIN: We feel like as the creators of the opera, I feel personally, both of these views are totally unnecessary. You can't just be on the ground because you don't see enough. You can only be in the sky looking down because you don't see enough. You need the blend of people actually understanding what the individual lives of human beings moving through a city are like–that's the Jacobs perspective. And then also, the vision, the top down, the sense of how does the infrastructure get built to serve those needs. It's funny, Jacobs doesn't talk much about how you create density, how you actually get people into the city, how you deal with trains and things like that. Of course, Moses doesn't deal with trains either, but we need to be able to think about those large scale movements of people and that's certainly something he was concerned with.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: But from a narrative standpoint, these two are the contemporary analogy to David and Goliath. They are essentially myth. And I wondered what your frame of mind was when you decided to and then began to opera-fy, these two people, perhaps beyond their historical selves.

JUDD GREENSTEIN: So much of opera is myth. It's myth making. It's myth telling and we want to preserve that. We want to show them as human beings but we also want to allow them mythologies to express themselves in the opera. We go back in time at the start of act two to see him find this land that nobody had discovered in Long Island and turn it into one of the greatest public beaches that the world has ever seen. We're seeing his own self mythologizing as the beach is being constructed. And as he's imagining what all the people are going to say when he's finished it and give him the glory that he finally deserves.

[CLIP: Opera]

JUDD GREENSTEIN: Tracy K. Smith, our poet laureate who is also writing the libretto for the opera, Tracy says we're not telling the story of Moses and Jacobs. We're telling our story of Moses and Jacobs. What motivated them? what drove them? How do we find empathy with these characters as human beings even though there's also a sense that they are myth? And so Moses, when he loses, this is not something he's used to, how do you tell the story of Moses internally responding to the sense of loss for the first time? We go deep inside his head.

[CLIP: Opera]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Is Moses a figure brought down by his own hubris?

JUDD GREENSTEIN: I mean, what we see this myth is, actually strangely, as a love triangle. Moses and Jacobs both love the city with as much passion as you've ever seen in two people. But they express that love in completely different ways. But they do have that love in common and at the center of the entire opera are the people of New York City itself. And we actually see them as the main character. So there's a scene where that's all these different characters that are taken from Jacob's own writing, her own observations. You have the fruit man. You have the longshoreman who's going in to get a drink. You have the girls on the street at night going out. And Jane Jacobs notes that they're safe because of all the people the eyes in the street.

[CLIP: Opera]

JUDD GREENSTEIN: And in this scene, everybody is coming together and imagining what that world would look like when people are moving together, not in synchronicity, not in the Moses world where everybody marches lockstep in his vision of what New York should be but--.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: You describe him as a fascist.

JUDD GREENSTEIN: Well, you know, I mean, Moses is certainly an autocrat. He certainly believes that he knows what's right and he knows how to get the power to make sure that everybody else follows his vision. And that's what he sees as love. That's what he sees as how he can best serve the city.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Why Jacobs and Moses? What sparked this effort?

JUDD GREENSTEIN: Josh Frankel, who's the director of the opera and also the animator, he and I both grew up playing in Washington Square Park. This story was always, sort of, our personal myth. The story of Washington Square Park being saved. But then when you dig deeper, you realize it's a story that's actually being told in every generation, certainly now, with as much building as has happened in a long time in New York City. We're facing all these questions of how do people make decisions? How do people stand up to the decisions that they don't believe? How do they take control of their neighborhoods? And even more fundamentally, how do they realize that things have not always been the way that they were and they don't always have to be the way that they are now?

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Judd, thank you very much.

JUDD GREENSTEIN: Thanks so much for having me.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Judd Greenstein is the composer of A Marvelous Order.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]