The Rise and Fall of Fake News

( On the Media/WNYC )

BOB GARFIELD: This is On the Media. I’m Bob Garfield.

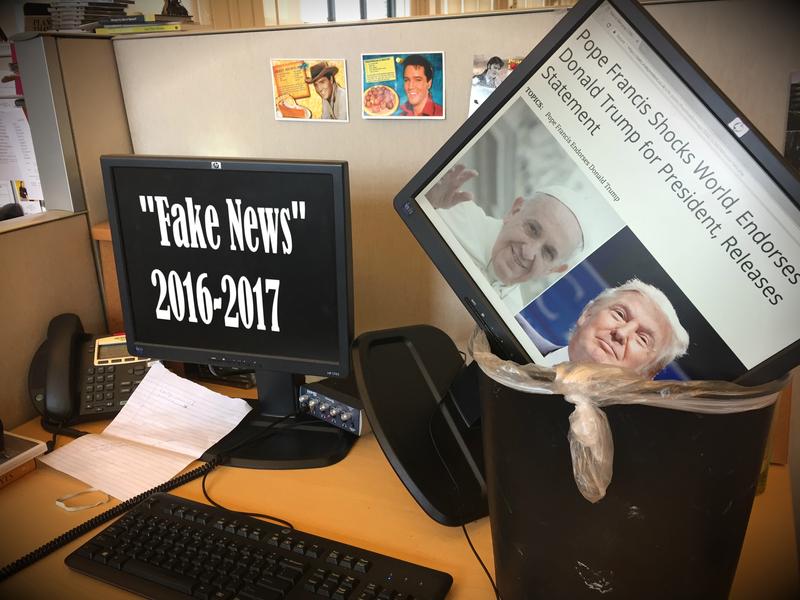

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And I'm Brooke Gladstone. And now, a look at the meteoric rise and immolation of the phrase “fake news.” In the days following the election, the media were adrift, destabilized, craving for some explanation for how they’d gotten so much, so wrong. “Fake news” emerged from the myth.

[CLIPS/MUSIC UP & UNDER]:

FEMALE CORRESPONDENT: Tonight, faking news, political lies spread on social media by unsuspecting users.

FEMALE CORRESPONDENT: Did it change the course of the election?

FEMALE CORRESPONDENT: While established media outlets are brands built on accuracy, rogue websites, some masquerading as legitimate, are reporting misinformation, and it’s spreading like wildfire online.

FEMALE CORRESPONDENT: Flat-out lies, deemed as the truth, the “fake news” writer who says he is the reason Donald Trump will be in office and the guilt he feels about that now.

[END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: A seductive narrative for many, and it seemed to have data backing it up.

[CLIPS]:

FEMALE CORRESPONDENT: BuzzFeed News says fake election stories sparked more interest than real ones. BuzzFeed counted comments and shares on Facebook during the last three months of the campaign and found that hoaxes and stories from biased sites far outperformed reports from major news outlets.

MALE CORRESPONDENT: All but three of the top twenty fake news stories were anti-Clinton or pro-Trump.

MALE CORRESPONDENT: Now, the number one trending article in that time was about Pope Francis endorsing Donald Trump for president, and that wasn't even true.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Finally, it all made sense. Fake news had poisoned the well, and boy, did we want you to know it.

[CLIPS]:

MALE CORRESPONDENT: A major crackdown announced today by Facebook. Since the election, the social media giant has come under fire for the spread of fake news on its site.

MALE CORRESPONDENT: Last weekend, a fake news story about Clinton led to a shooting in Washington, DC.

HILLARY CLINTON: It’s now clear that so-called “fake news” can have real-world consequences. It’s a danger that must be addressed.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: But maybe it was too catchy. It started as a liberal meme, but then the right ran with it.

WFB REPORTER BILL McMORRIS: Fake news is whatever people living in the liberal bubble determine to be believed by the right and, of course, it’s based on a complete hoax.

MALE CORRESPONDENT: …as this headline from the Washington Post, “Russian operation hacked a Vermont utility showing risks to US electrical grid security, officials say.” Of course, if you got the article now, you’d see a huge correction on top. It turns out the whole thing was fake news, and not the only fake news in that highly fake newspaper.

KELLYANNE CONWAY: I think the biggest piece of fake news in this election was that Donald Trump couldn’t win.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And then the reductio ad absurdum, “Some news is fake, therefore, all news is fake.”

FEMALE CORRESPONDENT: The President-elect angrily denied the claims contained in a dossier, calling it “fake news.”

PRESIDENT TRUMP: It’s all fake news. It’s phony stuff. It didn’t happen.

JIM ACOSTA: Can you -

PRESIDENT TRUMP: I am not going to give you a question.

JIM ACOSTA: Can you state, can you state categorically –

PRESIDENT TRUMP: You are fake news.

[END CLIP]

[MUSIC/MUSIC UP & UNDER]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Co-opted in the blink of an eye, farewell fake news, and don’t let the door hit you on the way out because probably the media made too much of it, to begin with, because BuzzFeed released a new study, this time measuring whether people actually trust the news they see online, and it found that even though more than half of people get news from Facebook, just a little over a quarter of them say they actually trust it. So maybe we're not quite as gullible as we feared. And another study, carried out by two economists, found that only 15% of people even remembered seeing the fake news they read and, of those who remembered it, only half believed it, a mere 8% of the total. Not only that, but some of them claimed to remember “fake fake” news headlines that the study's authors had invented as placebos.

Matthew Gentzkow who co-authored that study, told us that once you account for the placebo effect, even fewer than 8% believed or even recalled them, which leaves us where? Was fake news the great moral panic of 2016? Is it still in our midst, summoning its strength, waiting to strike again?

CRAIG SILVERMAN: I think we’re at the point where, honestly, the term has become almost meaningless.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Craig Silverman is media editor for BuzzFeed.

CRAIG SILVERMAN: Today, I used it in a headline and I kind of felt bad about that, [LAUGHS] to be honest with you.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Silverman is a longtime fake news researcher and the author of the original study that many use to suggest that fake news might have swung the election. He’s also the author of the more recent study that suggests that that’s probably overstating the case.

CRAIG SILVERMAN: We surveyed about a thousand American adults and we asked them two things. One was, where did you get news from in the last 30 days? Fifty-five% (55%) of people said they had gotten news on Facebook in the last 30 days and 56% of people said they had gotten news from broadcast TV in the previous 30 days, which is pretty remarkable.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: You also asked about trust?

CRAIG SILVERMAN: Yeah, so this is where a big gap opened up. For people who had gotten news from broadcast TV in the previous 30 days, 66% of them said that they trusted all or most of the time, and when it came to newspapers, it was even higher; it was 74%. But for Facebook, only 27% of them said that they trusted that information all or most of the time.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: A very high degree of skepticism, which is reassuring.

CRAIG SILVERMAN: Yeah, but most people in these kinds of surveys rate themselves very good at spotting something that is fake or not fake. We overestimate our ability on that. We always consider ourselves to be very rational beings, and this is especially true for journalists. We think, oh, I'm not gonna get fooled, I’m not gonna fall for something, but we’re all susceptible to this.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Well then, what was the point of your study, if you can’t believe what people say? That’s cold comfort, indeed.

CRAIG SILVERMAN: Well, you know, that’s science. [LAUGHS] We, we, we worked with researchers who do a lot of public opinion polling and we spent a lot of time trying to craft the questions, but ultimately you can’t control for everything. And so, we need a lot more research and we need the platforms to open up and give more data to more researchers.

One of the things that happened with fake news, it became kind of a political football, and so I think we lost some of the genuine conversation around its impact.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So you think that the news media, in general, have been overstating its power?

CRAIG SILVERMAN: It didn't give Trump the election but it is confusing a certain segment of the population, and it's certainly getting a fair amount of exposure on Facebook. Fake news is really interesting because of what it says about our media ecosystem. What I call “fake news” is stuff that’s 100% fake, usually created for a financial motive. For example, the pope endorsing Trump hoax originated on a site that was filled with completely fake information, run by a guy out of California who had like 40 other sites like that, and he had run literally hundreds of fake news articles over the course of 2016.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: He sold ads around them?

CRAIG SILVERMAN: It was becoming a pretty good business. And so, I think a lot of people flooded into that. The stuff that worked well on Facebook was the stuff that was more aggressive, it was more shocking. I spoke to somebody who runs a pretty large hyper-partisan conservative site - he’s got more than 2 million fans - and he was complaining to me that the kids in Macedonia that were pushing fake news did not launch the sites because they loved Trump. They did it because it was a business opportunity.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm.

CRAIG SILVERMAN: And they skewed it. If you wanted to compete, you had to do the misleading stuff. And so, I think that's one of the stories of the election, of how, you know, the performance of the fake stuff on Facebook created so much noise, so much misleading and false information, that in the end people may not have said that they believed the headlines, but I think there were a decent amount of people who were awash in this kind of information. So I wonder if, as people who were already inclined to be pro-Trump shared this stuff, did it polarize them more, did it get to their edges of their network and other people who maybe hadn’t made up their mind started to see this stuff a little bit more? And I don't think it's gonna change their mind but I just wonder if that repetition of it over time starts to have an effect on people.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: We have talked a lot over the last decade or so about the disappearance of the public square, a place where people can go and, and share in the same pool of information. It’s been more or less replaced with Facebook, with the hundred- thousand, million different little filter bubbles.

On the other hand, circling back to why we’re having this discussion, your study about the high degree of skepticism people claim to have about this information, compared to television or newspapers –

CRAIG SILVERMAN: Mm-hmm.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: - should we be feeling the kind of moral panic that so many of us do, that all this garbage is out there?

CRAIG SILVERMAN: The thing that concerns me most, when you start to get that kind of information that is fed to you, to go to your emotions, to go to your beliefs, that is sometimes fake, sometimes misleading, it polarizes you more and then it's almost like eating junk food or eating a lot of sugar and you seek more of that out. And the algorithms are built to give you more of what you want. And when they go and they read something that's got another point of view or that doesn't present it in that same kind of hyper-partisan way, what’s the reaction going to be? Are they going to read that and be like, this isn’t the news I’m used to? Will people forget what an actual kind of fact-based report that isn't torqued looked like? That's the dystopian kind of thing, and [LAUGHS] we’re not, we’re not there, but you can sort of see how the combination of algorithms and our human biases and the massive reach of platforms and a pretty polarized society and a polarizing administration - that is the thing that I worry about most.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So if the problem isn't, strictly speaking, changing people's minds but increased polarization, fact checking isn’t going to help that, is it?

CRAIG SILVERMAN: Real or fake, we love to see and consume information that aligns with who we are as a person and what we already think and believe. We think, oh, I'm not gonna get fooled, but we’re all susceptible. So the main thing, I think, is just to realize that there are certain amounts of interacting with information that we control and there are certain things that we do because of our reptilian core. And when I read something that makes me feel good, I try to make myself question why that is. And I think that level of emotional skepticism of your own emotions is maybe the next level for people to try and get to.

The other piece of it is when you see bad information out there and it’s coming from somebody you know and somebody you trust, rather than leaving them a comments on Facebook, try to talk to them on the phone and try to understand because if we’re worried about polarization, actually being able to talk to people is probably a good defense against that.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Margaret Sullivan, who used to be the New York Times public editor and now writes a media column for the Washington Post –

CRAIG SILVERMAN: Mm-hmm.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: - quotes George Washington University Professor Nikki Usher, saying that the speed with which the term “fake news” became polarized and, in fact, a rhetorical weapon illustrates how efficient the conservative media machine has become. And so, Sullivan goes on to write, “Here’s a modest proposal for the truth-based community. Let’s get out the hook and pull that baby off the stage.

[SILVERMAN LAUGHS]

Yes: Simply stop using it. Instead, call a lie a lie. Call a hoax a hoax. Call a conspiracy theory by its rightful name. After all, ‘fake news’ is an imprecise expression to begin with.”

CRAIG SILVERMAN: I'm sort of onboard with that, I have to say. I feel like it's lost a lot of its meaning and its nuance. I have genuinely had a couple of conversations with my editors that maybe we should be talking about hoaxes and propaganda and conspiracy theories, one, because these are long-known terms and maybe people actually understand the distinctions between them better. I mean, to me fake news will always be stuff that’s 100% false, [LAUGHS] created for financial motive, but that definition has been lost, I think.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Okay. Craig, thanks very much.

CRAIG SILVERMAN: Thank you.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Craig Silverman is the media editor for BuzzFeed.

[MUSIC/MUSIC UP & UNDER]

When a news outlet gets something wrong, owns up to it and apologizes, that’s a mistake, not fake news. To call the institution of American journalism “fake,” based on the errors it will inevitably make, is a, by now, familiar ploy of the new administration. Cognitive linguist George Lakoff told us it’s a tactic known as the salient exemplar. Don't fall for it. As a nation, we stand up for freedom of speech but there are no slogans proclaiming, no watchdogs protecting your right to actually listen. That’s an intensely personal choice, not a political act, until now.

BOB GARFIELD: That’s it for this week show. On The Media is produced by Meara Sharma, Alana Casanova-Burgess and Jesse Brenneman. We had more help from Micah Loewinger, Sara Qari, Leah Feder and Kate Bakhtiyarova. And our show was edited - by Brooke. Our technical director is Jennifer Munson. Our engineer this week was Terence Bernardo.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Katya Rogers is our executive producer. Jim Schacter is WNYC’s vice-president for news. On the Media is a production of WNYC Studios. I’m Brooke Gladstone.

BOB GARFIELD: And I’m Bob Garfield.