Resurrecting Kitty Genovese: A Love Story

BROOKE GLADSTONE: We all know about the murder of Kitty Genovese on a New York City street in 1964. It dishonored the city, all cities, as the emblem of urban dehumanization. The lead in The New York Times read, “For more than half an hour, 38 respectable law-abiding citizens in Queens watched a killer stalk and stab a woman in three separate attacks in Kew Gardens.” Kitty's teenage brother, Bill, read the story and believes it made him the man he became. But is the story true?

The new documentary, The Witness, follows Bill’s long and arduous pursuit of the witnesses to Kitty’s death and her life, the so-called “witnesses who shamed us all.”

[CLIP]:

MALE CORRESPONDENT: Tomorrow marks what many people regard as one of the most shameful anniversaries in New York City history.

MALE CORRESPONDENT: Fifty years ago, her murder led to the adoption of the 911 system.

MALE CORRESPONDENT: Police discovered that more than 30 people had witnessed her attack and no one had picked up the phone to call the police.

[END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: James Solomon directed and produced The Witness. Welcome to the show.

JAMES SOLOMON: Great to be here, Brooke.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So the film's narrator, Kitty Genovese's brother, Bill Genovese, was 16 when she was murdered. The film is really about him, isn't it? You’ve called it a love story.

JAMES SOLOMON: It is a love story. Bill was determined to reclaim his sister's life from her death. Kitty was, as he describes in the film, his mother and father combined. She heard him, listened to him, affirmed him, validated him, but it wasn't just the fact that he lost this sister who he adored so much, but the way she reportedly died. That story shaped the rest of his life.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: You met him in the course of researching a feature film about Kitty Genovese. You are a scriptwriter. Then you decided to make your own directorial debut by creating this documentary with Bill at the heart of it.

JAMES SOLOMON: What I discovered was that I could not possibly do justice to the story of Kitty Genovese by writing it, that the people who could best tell the story of who she was and what happened that night were the people who actually lived it. Bill was determined to find out for himself what actually happened that night. And so, for the past decade, Bill has been on this quest.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Martin Gansberg, who broke the story in The Times in ’64, was working under the supervision essentially of New York Times Editor Abe Rosenthal, who’d spoken to a police chief and later wrote, “38 Witnesses” about the case and about the “bystander syndrome,” also known as the “Genovese syndrome.” The New York Times has since written stories revising that original account. What he seems to say is that the story may or may not be entirely true but the syndrome that I identified that is now being taught in sociology classes is too important to mess with.

[CLIP]:

MARTIN GANSBERG: I can't swear to God that there were 38 people. Some people say there were more, some people say there were less but what was true, people all over the world were affected by it. Did it do anything? You bet you your eye it did something, and I’m glad it did.

[END CLIP]

JAMES SOLOMON: Journalists, as you know, have this saying, some stories are too good to check. And the story of 38 having watched for more than a half hour simply just wasn't true. How did that story come to be? Bill would have to jump back 52 years to get the answer to that, by tracking down the journalists who covered it.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: One of whom is Mike Wallace.

[CLIP]:

MIKE WALLACE: No one investigated the 38, no one followed up on it or anything of that nature?

GABE PRESSMAN: Do you have any feel for why that would have been with this case versus any other case?

MIKE WALLACE: Because it was taken seriously by The New York Times.

[END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Probably the most important witness he finds is a neighbor of Kitty’s and a friend named Sophie Farrar.

JAMES SOLOMON: Well, think about it, for a half-century your entire family lives off the understanding that your daughter, your sister died alone, and then you find out, well, actually, she died in the arms of a friend.

[CLIP]:

SOPHIE FARRAR: It kills me when I think about it, black leather gloves and all cuts all through the gloves on her both hands. I only hope that she knew it was me, that she wasn’t alone.

[END CLIP]

JAMES SOLOMON: It makes you question the narratives that shape your life and the way false narratives change the course of your life - Bill’s life propelled by a false narrative.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: In the film, there's a suggestion that Bill Genovese enlisted in the Marines and went to Vietnam, in part as a response to Kitty's murder because he didn't want to be an apathetic bystander to the war, in the same way that those witnesses supposedly were to her death. But do you think he really would have acted differently, had he known the real story?

JAMES SOLOMON: Well, Bill answers that question in, in a variety of ways. He definitely felt that he needed to prove that he was not like those people that night. Even when he was in Vietnam, he was the one who would raise his hand for every dangerous mission. He’s also told me that had Kitty lived, she would have talked him out of going to Vietnam.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: One thing that we see is that he is striving, against many odds, to get to the truth of this story, and he does it without his legs. He travels either in a wheelchair or he just basically slides across the room. He is unselfconscious about that. And yet, it seems - almost like a visual metaphor, in a way, for the damage he sustained.

JAMES SOLOMON: The people who appear in the film, the witnesses who were there that night, in particular, it is only because of Bill’s understanding, in a sense, of trauma that I think a lot of the people were willing to open up. This is not the selfie generation that are talking. Because Bill is extraordinarily empathic as a person and also because he's walked the walk, people were willing to open up to him, and so, what unravels over the course of the film is a level of insight into what happened that night, the effect of it that I don't think anyone else could have possibly brought out.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Among the people Bill spoke to was the murderer's son, a man named Stephen Moseley, a former prison guard who later became a preacher. You draw an interesting parallel between the two.

JAMES SOLOMON: They’re two men who are stepping outside the comfort zone of their family. They are determined to meet each other, for different reasons, but against the desires of their family. And they both are holding onto narratives that in the course of their conversation are challenged.

[CLIP]:

STEPHEN MOSELEY: Let me just say this here, I, I was kinda apprehensive about talking to you. From what I’ve understood, there was a Genovese crime family. Are you related to the crime family of Genovese?

BILL GENOVESE: No, not at all.

STEPHEN MOSELEY: I’ve always been told that it had been the, the crime family that Kitty was from.

[BOTH SPEAK/OVERLAP]

BILL GENOVESE: The truth was, Stephen, between you and me, it’s not true.

STEPHEN MOSELEY: Everybody in my family says to me, you know, you’re crazy, you shouldn’t go there. You may not come back. [LAUGHS]

BILL GENOVESE: So you’re not only cordial for coming here but you’re courageous for coming here. [LAUGHS]

[END CLIP]

JAMES SOLOMON: Winston Moseley’s family and Kitty Genovese’s family has been holding to these stories that on closer examination may not be true.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Bill talks about the moment in Vietnam when his legs were off and he thought he would bleed out, and he projected himself back to what he imagined his sister had gone through.

JAMES SOLOMON: And the closest Bill ever got to experiencing what it was like for his sister that night occurred in July of 1967, when Bill was on patrol and a remote-controlled detonated land mine blew up and he was thrown into the rice paddy, waiting and hoping for someone to come to his aid and finding himself all alone. And he just said that that was the first time in Vietnam he thought of his sister.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Kitty's nieces and nephews, who she'd never met, didn't know who she was. For one of them, her name came up in class in high school. She didn't even realize it was her own aunt.

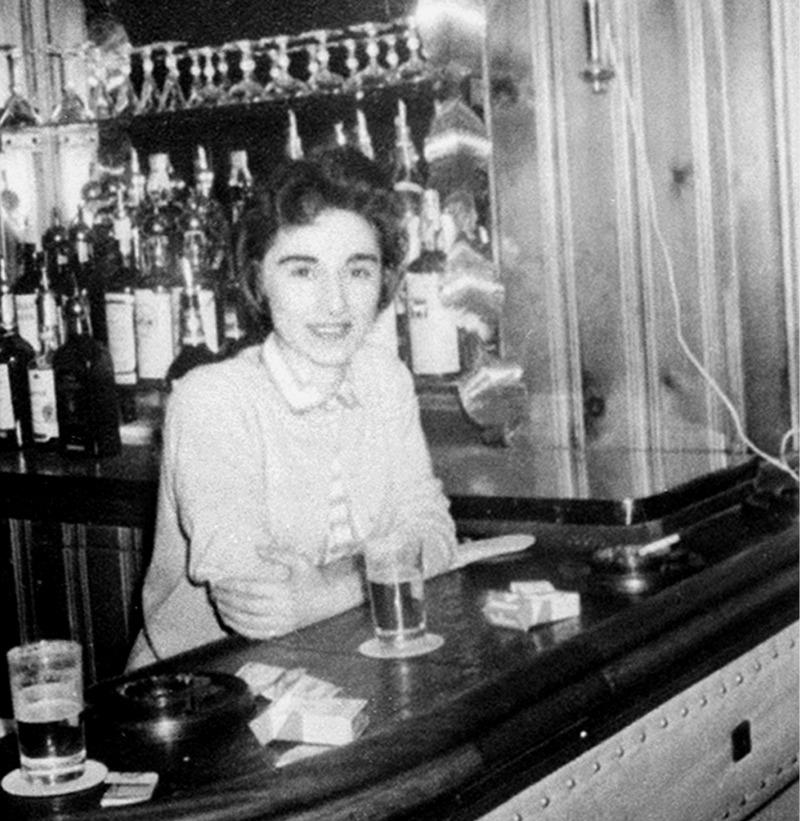

JAMES SOLOMON: That is one of the great tragedies. The account of her death was so public and so horrific that it erased her life within her own family. Bill’s brother Vin in the film refers to, the only way we could deal with her death was to not talk about her life. Kitty was a remarkably fascinating and compelling figure, a 28-year-old woman working in a bar, managing the bar.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: A live wire in high school who never had any grand intellectual ambitions. She just seemed to want to be free.

[CLIP/MUSIC UP & UNDER]:

WOMAN: We played hooky. We went to the beach or here in the park or smoking on the roof. And she was the head of the pack.

[END CLIP]

JAMES SOLOMON: Yeah, she’s driving a red Fiat, living with a woman, Mary Ann. And what Bill does in the film is reveal a person that we all would feel, gosh, I really wish I knew her.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Bill didn’t even know she was gay.

JAMES SOLOMON: He did not. Really, the greatest sadness is for Mary Ann, who was Kitty's lover. They were living in Kew Gardens and after she died the family didn't know and there was no connection between the family and Mary Ann, until this film. There’s very poignant moment. Bill and Mary Ann are speaking, for the first time in virtually a half-century, and Mary Ann says to Bill, I, I just wish I, I could have done something. And Bill says, yeah, I know, me too, essentially.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Now for the controversial last scene. He - you - hire an actress simply to scream. We meet the actress. There's no effort to make this be a recreation in a History Channel or a Discovery Channel sense of the word, at all. We see him putting up signs for the neighbors to be aware and not to worry. It is, nevertheless, horrifying. I wonder if you aren’t going to come in for some criticism for how horrifying it is.

JAMES SOLOMON: The film documents Bill’s 11-year journey and, at the end of that journey, Bill had this desire and this need to immerse himself in what took place that night, He had been talking and thinking about what it was like, and with the limitations of a half-century you can't recreate exactly what it was like. But the street stands like a movie set. Austin Street is just the way it was, virtually, as it was in 1964.

And so, on a night on April 1st, 2014, on a night not so dissimilar to the night that his sister was murdered –

[THE WITNESS/AUDIO RE-ENACTMENT OF KITTY GENOVESE’S SCREAMS]

- he was able to feel what it was like.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Did you know how this story would end when you began?

JAMES SOLOMON: Brooke, you know – you knew my brother very well. My brother John was a contributor to this show and became a good friend of this show, and you and this show has a huge place in my heart. In 2004, I was making a film about a brother who lost a sister. I had no personal understanding of that kind of loss. Along the way, in making this film, my own brother John, the person who I looked up to more than anyone in the world, got sick with leukemia and died a couple of years later. So what was once an abstract understanding of sibling loss ceased to be.

And so, no, I had no idea what the feeling or experience or importance of this film would be like for me. We followed Bill and I had no idea as to where it would take us. I, I think Bill and I thought it would take six months. We never thought it would take 11 years. And his family now knows who Kitty, the person, was, not just Kitty, the victim. Over a half-century, this man is determined to reclaim his sister, her life from her death.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

It’s, in my estimation, the ultimate love story.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: James, thank you so much.

JAMES SOLOMON: Thank you, Brooke, so much for having me on On the Media.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: James Solomon is the director of The Witness, which is now available on Netflix, iTunes and Amazon.

BOB GARFIELD: Coming up, in Ukraine a state-appointed archivist is singlehandedly cleansing his country’s murky past.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: This is On the Media.