Ever since the 2016 election, we've been pondering the obliteration of our norms, but seen in the context of history that's normal -- the First World War, the Depression, the Second World War, jazz, rock 'n roll, the Vietnam War, alienation and the internet. Keith Bybee, author of How Civility Works, says every generation of Americans has found a reason to bemoan the end of courtesy and respect, but the fact is civility can be a tool of oppression.

KEITH BYBEE: Jim Crow segregation was surrounded and sustained by a racial etiquette. Martin Luther King spoke about this quite eloquently in his letter from Birmingham Jail. You don't call the wife of an African American “Mrs.” She always gets addressed by her first name. An African American male adult is never “Mr.” He is “Boy” or “John.” In order to be a member of polite society defined by such a racial etiquette was to enact, through your conventional good behavior, a racial hierarchy. The sit-ins which were, in part, efforts to change laws, were direct confrontations with that etiquette. It wasn't ever enough for the civil rights movement just to seek policy change. There had to also be social change, one form of civility extended to all races, so that it would be possible for people to interact as equals.

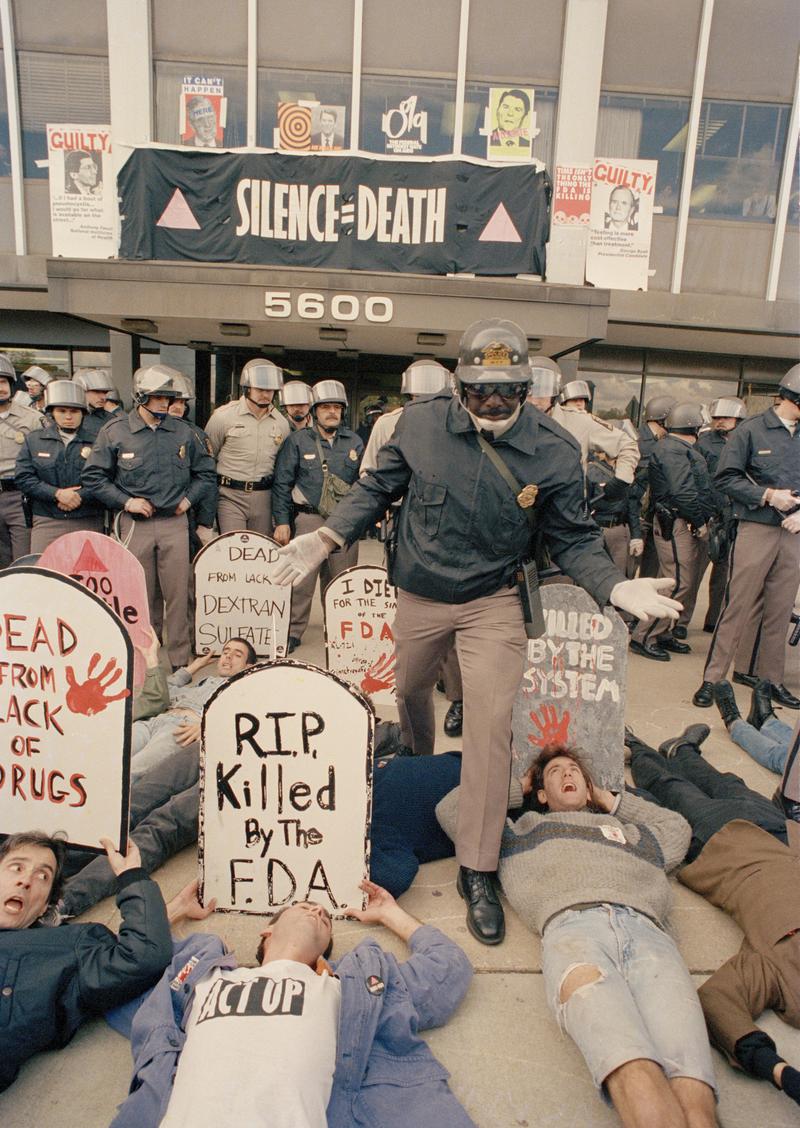

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Talk about then how etiquette violation can be a political tactic. You offer a really good example of what you call “manner-based intimidation,” the group called ACT UP.

KEITH BYBEE: That’s right, so during the 1980s in the Reagan administration, as the AIDS crisis was becoming more and more manifest, decorum at the time precluded discussion of non-heterosexual practices. Decorum at the time also sidelined or marginalized expressions of grief or mourning in public spaces. ACT UP, to bring greater attention to the AIDS crisis and to demand a more proactive response from government, abandoned appropriate behavior. They staged these quite dramatic takeovers of town hall or city hall meetings and legislative hearings. They stayed die-ins. This tactic initially was understood as counterproductive. The idea is that they should play along with the rules of civility that are currently in place. Today it’s called tone policing, when you confront someone who's engaged in protest or some form of obstreperous behavior and you say to them, you'd be a lot more effective if you would calm down.

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

And what it does, right, is it redirects the conversation away from the issue that the protester is trying to call attention to and says, no, the problem is not the AIDS crisis or the problem is not police brutality, instead, the problem is, is your style of complaint.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Athletes taking the knee denounced as unpatriotic and disrespectful.

KEITH BYBEE: Policing of tone, I don't think, is just atmospherics. It really is a way of conveying a different understanding of the respect that people are owed.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm. [AFFIRMATIVE]

KEITH BYBEE: It, it taps into fundamental issues.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: From respectfully taking a knee to yelling at a diner, to cursing out the president. [LAUGHS] I, I wonder if there is some sort of range and can you distinguish among them or are they all the same thing?

KEITH BYBEE: You know, there’s no authoritative institution that tells us what civility is, that tells us how to update civility when times change. That kind of debate surfaces sometimes a deeper criticism that we should be without civility at all, like, let's just say what we think. And the patron saint of this perspective is John Stuart Mill and his powerful essay, “On Liberty,” where he said, you know, we should have a contentious public culture, we should have [LAUGHS] people shouting at each other in restaurants.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: He was deeply suspicious of civility as a tool of oppression.

KEITH BYBEE: Accusing people of being rude or uncivil as a way of, in Mill’s language, stigmatizing them as being immoral. Interestingly, Mill, himself, ultimately came down in favor of civility. He thought that there should be rules of temperate speech, if they could be designed and implemented in a way that would give respect to all merited arguments.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And I thought he was a realist.

KEITH BYBEE: That does sound pretty softheaded, right? And so, you wonder why would someone like Mill shift gears like that. Why would this hardheaded proponent of contention and disputation suddenly go wobbly? I actually think it grew out of his very commitment to robust, uninhabited, wide-open debate. What civility and, really, what good manners do, are provide you a mechanism for conveying your integrity. He sought and he thought rules of temperate speech which were more egalitarian and fair would actually underwrite a free-speech society.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: But you've already argued that civility is political and, therefore, the rules will always be determined by the powerful.

KEITH BYBEE: It’s also the case, though, right, that politics is never finished, so it's a call to action because civility is constituted through political conflicts. So get out there. Join the argument. Mill, in general, said, you can go as far as you want so long as it doesn’t hurt another person.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Finish up then with a certain paradox that you alluded to when you said that John Stuart Mill thought that civility was, in a sense, a reflection of character, and then you went and you quoted François de La Rochefoucauld who said, hypocrisy is the homage vice pays to virtue. What he meant is even if you're lying about how you feel, you're still behaving in a virtuous way and that’s better for society.

KEITH BYBEE: When we’re honest with one another, we often discover not our true commonalities, what we discover is how much we really don’t like each other. And if we’re in that kind of society, which is riven with disagreement, yet, we still need to get along --

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Civility enables us to lie in order to get along, and what's wrong with that? [LAUGHS]

KEITH BYBEE: Right. Well, [LAUGHS] yes. Now, you can say, well, I, I don’t want to live in a society where people aren’t really telling me what they really think. And I, I think that that perspective is really held by only people who have never lived with complete honesty, which is very unpleasant. Civility gives us an easily-deployable means for conveying a basic decency.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: At the same time, you're okay with yelling at Kirstjen Nielsen in a restaurant.

KEITH BYBEE: Right. I contain multitudes, Brooke. [CHUCKLES]

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

Shouting in the restaurant is part and parcel of determining what will count as our baseline of respect we owe one another in public life. So that’s part of the making of the sausage. Once the sausage is made, and this metaphor is going to break down pretty quickly, then [LAUGHS] people can pose with that sausage, you know, whether it’s inauthentic --

[BOTH SPEAK/OVERLAP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Yep, it’s just broken down!

KEITH BYBEE: -- and hypocritical.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Okay!

KEITH BYBEE: I think we should keep this in.

[LAUGHTER]

I think this sausage thing could be big.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: [LAUGHING] But the thing is, is that a lot of people worry about the slippery slope, but our rules of discourse seem to ebbed and flowed forever.

KEITH BYBEE: It’s not as if having gone in one direction we can't go backwards. We've seen that our manners have become more inclusive and egalitarian over time but having made that progress doesn't mean that we couldn't step backward. I don't think we’re going to dispense with civility. I think we might radically change the way in which we operationalize it over time. But I don't think that we will shed the requirement [LAUGHS] for civility. I, I don't think it's something we get over. I think, rather, it's the means through which we realize our ideals of justice and fairness.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Thank you very much.

KEITH BYBEE: Well, thanks for having me on.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Keith Bybee is a judiciary studies professor at the Syracuse University School of Law and author of How Civility Works.

BOB GARFIELD: This is On the Media.

[PROMOS]