BOB: From WNYC in New York this is On the Media, I’m Bob Garfield.

BROOKE: And I’m Brooke Gladstone. This week, we’re engaging in some chillingly informed speculation: what would happen if we, as a species, lost access to our electronic records? What if, either by the slow creep of technological obsolescence or sudden cosmic disaster, we no longer could draw from the well of of knowledge accrued through the ages? What if we fell into… a digital dark age?

We do know that the march of progress, the steady extinction of audio cassettes and videotapes, floppy discs and operating systems, have extinguished parts of your personal history, because you told us.

GEBEL: This is David Gebel in New York City and the loss that comes to mind is wondering why I ever got rid of that little tiny cassette that used to be inside 1980s phone answering machines. Because I kept it for a long time after my boyfriend died of AIDS in 1988 and I kept the last message I had from him. And it was not a particularly interesting message, it just was his voice. And I kept thinking, what's this cassette ever going to fit, and the day came when the machine just broke and I tossed it and got rid of that little tiny cassette. And I wish I hadn't. 'Cause it would be nice to hear his voice at this point.

BROOKE: In our eagerness to embrace the limitless storage capacity of new technology, we are losing the documents of our past. This week, a guide to the once and future digital dark age. The first scenario is not speculation. It happened.

BOB: As far back as 1990, the New York Times described NASA’s massive archive from early space flights as edging closer to the brink of technological extinction. The agency hadn’t thoroughly catalogued 1.2 million magnetic tape reels of images and data from 260 scientific missions. Hundreds of thousands of tapes were kept under (quote) “deplorable conditions.”

In fact, NASA says the original tapes of the Apollo moonwalk probably were erased and reused in the early 1980s. That grainy image you’ve seen of the giant leap for mankind is really a copy of a copy. So are most photos from space.

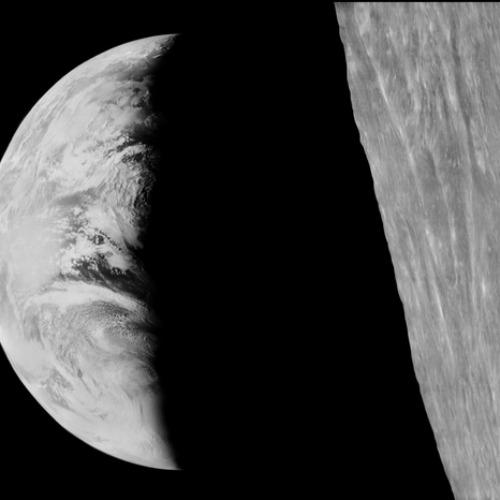

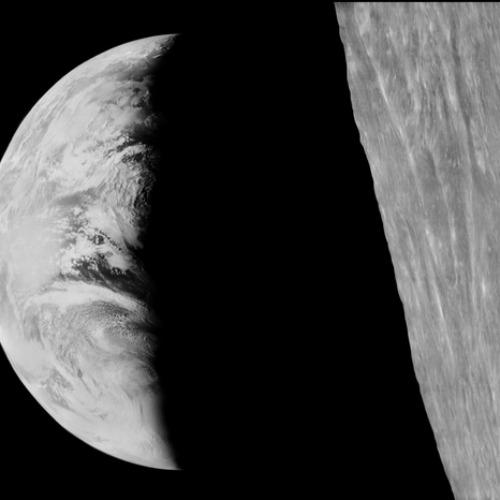

COWING: I remember the first image from Lunar Orbiter 1 that showed the earth rising above the lunar surface. Now technically it was setting, but it became called Earth Rise.

Keith Cowing is co-founder of the Lunar Orbiter Image Recovery Project, or LOIRP… which endeavors to rescue 1960s NASA data. Such as that iconic image, Earthrise. You’ve seen that black and white photo snapped in 1966. In the foreground, the vast craters of the moon. And floating above, where the lunar horizon fades into black: a bright crescent of the earth, with white swirls of atmosphere. When Keith Cowing first saw it, he was a young teenager.

COWING: As a matter of fact, I was getting in the car to go see the film 2001 for the very first time in theaters and I had a National Geographic book with me, and the frontispiece was that photo. So for me and many people my age this was really seared in my memory. And the way that we saw it, or at least I saw it, it has these lines though it, and it was pretty primitive, but this is the first time anybody had really seen earth in a context as part of the earth moon system.

BOB: The photo looked primitive because at that time, NASA’s ability to collect data, outstripped its ability to clearly display it, or even see it.

Images of the lunar surface taken by the five Lunar Orbiter spacecraft were so large, they were beamed back to earth in sections as data, then recorded to magnetic tape reels and printed out on photographic paper, and then photographed again.

COWING: They had these giant pieces of newsprint in an old church or a factory, and they just put 'em together and hung ‘em there and they said alright, now we can understand how this looks - and photograph it again. So, you know, right off the bat you're losing some resolution. And because of the way that photographic film worked and so forth, you get these variations towards the edges, the sort of zebra striping.

BOB: Once the Lunar Orbiter had fulfilled its mission -- to find a suitable spot for the Apollo 11 landing in 1969 -- nearly all of the thousands of 2-inch magnetic tape reels it recorded were either discarded or reused. That is, except for just one set, stored away in protective canisters sealed with… whale oil.

COWING: We don't really use whale oil anymore, but, that's sort of the secret sauce, apparently, to what helped keep these alive. Somebody just thought ahead, did exactly precisely what you'd need to do to keep these tapes in pristine condition

BOB: One full set of the original tape reels - with their whale oil - were passed around for nearly five decades, narrowly escaping destruction. In 2006 they resurfaced again, and the LOIRP was born. But what good are tapes if you don’t have a refrigerator-sized Ampex FR-900 tape drive to play them on? Nearly all of those machines had been lost, as well. But a former NASA employee, Nancy Evans, had miraculously used her own money to buy four of them for safe-keeping.

COWING: She stored them in a barn in her backyard in central California which is nice and dry, and they stayed there for years, and when we contacted her, her daughter now ran the place, and she was a holistic veterinarian, using acupuncture on animals, and when we went there to pick them up, there were the drives, just sitting there covered with dust, and farm animals walking around.

BOB: The early history of space exploration: stowed in a barn.

COWING: So we, fortuitously, had two independent paths that caused the tapes, and the drives, to still exist, decades later. Now we just had to make them work.

BOB: It was just the beginning of digital resurrection as Andy Hardy Movie. Hey, kids, let’s salvage our scientific legacy! The team happened upon an air conditioning repairman whose brother had worked with Ampex drives and could help rebuild them. The gang shopped for spare parts on eBay and at Radioshack. NASA offered them an empty McDonald’s in Silicon Valley to work in and they renamed it McMoon’s. And they found documentation of a mathematical formula needed to demodulate the images.

COWING: We just expected that we had some sort of guardian angel of techno-archeology that would just solve our problem in the most absurd way possible. And we had cobbled it all together, and then in a scene that was just like out of the movie Contact, where they're playing the transmission that was being sent back by aliens, and they said, well, turn it this way, turn it that way -- suddenly, there was the picture.

CLIP FROM CONTACT:

FOSTER: Can you clean it up any more than that Fisher?

FISHER: I'm working on it.

COWING: We saw in this case the white of space - which is the black of space, 'cause these images were negative -- and then the darkness of the moon, and when you flipped it, there it was. There was the image we were looking for, just like that.

BOB: The team published its first recovered image in 2008 - a streak-free version of Earthrise, seen in higher resolution than ever before. LOIRP has since rescued thousands of other images. But this was more than an exercise in nostalgia. The project has rescued clear images of the Antarctic captured by a satellite in the 60s. And NASA has found reels containing ozone levels from the 1970s. Both troves of baseline data for understanding the effect and rates of ice melt and climate change.

COWING: So we're A half century late, but later is better than never.

BOB: Keith, please tell me that today in 2015 NASA and other government agencies that are marshaling gigantic scientific projects are not going to leave it for future techno-archaeologists to jerry-rig solutions, that there is a plan in place to preserve what we are spending billions to discover.

KEITH: Well, no and yes.We have spacecraft that generate terabytes of data, like, on a daily basis. And it’s being stored on hard drives and hard drives fail. And if you store it on DVDs, well over time the plastic degrades. And so, archiving all this stuff, what do you archive it on? So I fear that, you know, we’re going to be losing stuff and unless the programs specifically say you’re gonna save your material in a certain way it may be lost.

BOB: Keith Cowing is a former NASA employee, and is now editor of the blog NASA Watch. He is co-founder of the Lunar Orbiter Image Recovery Project (LOIRP), but has since left the team.