BROOKE GLADSTONE: The philosopher Svetlin Todorov wrote that the 21st century is, quote, “obsessed by a new cult, that of memory.” David Rieff, author of In Praise of Forgetting: Historical Memory and Its Ironies, says that, in fact, the memorializing of collective historical memory has become one of humanity's highest moral obligations. And that, he says, is a mistake because collective historical memory has very little to do with history.

[MUSIC OUT]

DAVID RIEFF: History is about the past, whereas memory is about how we use the past for the purposes of the present.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: But you don't really think history itself is independent and autonomous, right?

DAVID RIEFF: Is there perfect history? Self-evidently not, but I do think history, when done properly, is critical history, looking at the past and not really caring whether what one finds out helps the good guys and thwarts the bad guys, etc., etc. There's a great English novel, The Go-Between by L.P. Hartley, and the first line is, “The past is another country. They do things differently there.” [BROOKE LAUGHS] Whereas, memory always seems to me to be deployed in the service of the present.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And you regard Santayana’s truism, “Those who do not remember the past are condemned to repeat it” as fundamentally false or, at least, hazardous.

DAVID RIEFF: I mean, I don't see how we learn anything from the past. I mean, if you look at the worst thing, say the Holocaust, did not stop the genocide in East Pakistan in what became Bangladesh in 1971 or the mass slaughter in Cambodia when the Khmer Rouge ruled or the Rwandan genocide? I mean, it doesn't seem to me that knowing about the past has saved anybody.

Now, if you're saying, is there a moral obligation to remember, we need to talk about whether or not that moral obligation serves peace, truth, justice. I think there are times when remembrance is a very useful thing, particularly in the immediate aftermath of a terrible event.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Yeah but if you’re talking about an immediate aftermath, a commemoration and a memory here are two different things. I mean, if the country pulls together after a natural disaster or, say, after 9/11 or something like that, that isn't the sort of formation of memory that you're really suspicious of.

DAVID RIEFF: In the immediate aftermath of conflicts, a lot of people believe that what you need to do is establish the truth, both for the sake of the victims, so that they have their stories told and if you're a relative you know what happened to somebody who was, say, disappeared by the Argentine junta. That seems to me a use of memory that can be very helpful.

But, again, even then I don't think it's always helpful. I mean, what do you do, for example, in a divided society, which, after a war, still disagrees about pretty much everything? Often these memories, far from leading to more consensus, more justice, more truth, are just a goad to war.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: You reported from Bosnia during the Balkan conflict of the ‘90s and you write in the book about having a, a piece of paper pressed into your hand with a date.

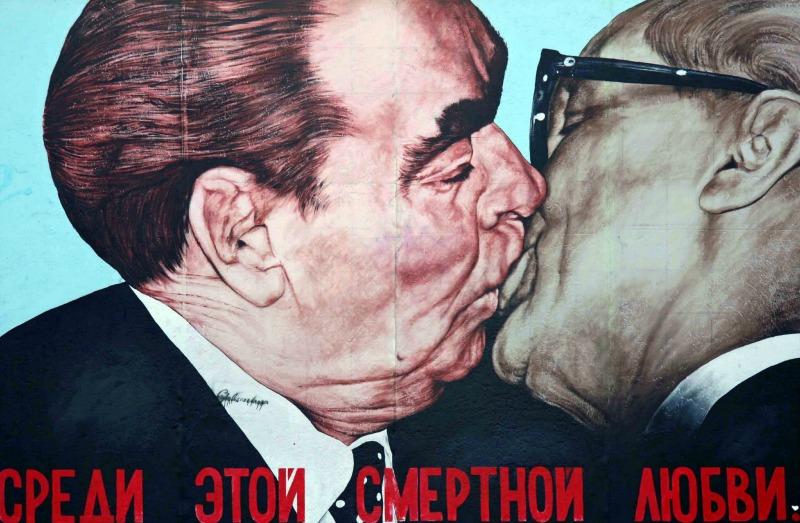

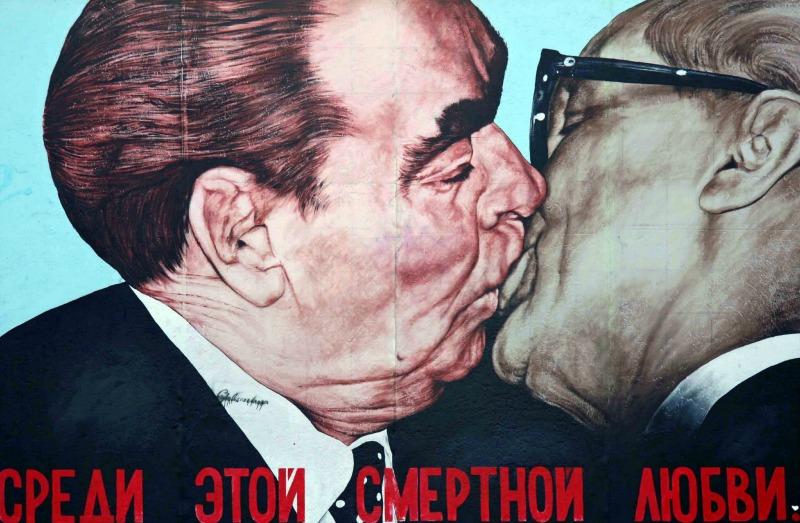

DAVID RIEFF: In 1993, I was in Belgrade and I went to interview a very extreme Serb nationalist politician and, as I was leaving the interview, one of his aides gave me a folded-up piece of paper. When I opened the paper, it just had a date written on it, 1453, the date that Christian Constantinople fell to the Turks. I mean, the message was perfectly clear. We're defending the West as the Byzantines defended Christian civilization from the Turks and that's what we Serbs are doing in Bosnia. That’s a goad to massacre.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Do you think that collective historical memory helps ensure that wars never end? You believe that, for instance, the battle over the Confederate flag that's going on now is partly a battle over the memory of the American Civil War, the war that was won by the North, but you suggest the memory was won by the South.

DAVID RIEFF: Well, I think it was. You know, the Southern interpretation, the war, brother against brother, nobility on both sides, that was the tenor in the official celebrations of the Centennial of the American Civil War. There’s a debate about what the war was, and on the Northern side people want to say, well, this was a war to extirpate slavery, there was nothing noble about the Southern cause. In the South, it was a commonplace in schools for teachers to literally, with a straight face, talk about the war of Northern aggression. The fact that a Southern battle flag could fly over various statehouses shows you, indeed, the victory of the Southern narrative.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: In the aftermath of the Dylann Roof massacre in June last year at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, where nine people were killed, you said the question of why the Civil War had been fought became, for the first time in decades, part of the mainstream debate. You, you really think that?

DAVID RIEFF: Well, African-American legislators have been trying to get these damn flags taken down, with no success whatsoever.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm.

DAVID RIEFF: And what happened after the massacre in Charleston was that suddenly a lot of white Americans in the South thought, wait a minute, maybe these flags really are an offense.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: You note that in resolving the Irish wars, people essentially agreed to disagree about the past.

DAVID RIEFF: Yeah, well, they did because nobody won. So you have communities that are still convinced of the rightness of their cause but still also have to live together. And today in Belfast, you’ll go from one neighborhood where the Union Jack is flying proudly to a - another neighborhood where the Irish Tricolor is flying proudly; they’re coexisting. But that seems to require them to have, in effect, said in the public discourse, we’re gonna largely forget about the past and think about the present and the future.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So far, so good, but also so recent. Agreeing to disagree, I don't know what the alternative is but it isn't a sustainable way of coping with these warring narratives. It seems to simply put off a later conflagration, rather than to extinguish it.

DAVID RIEFF: And in those cases, my answer would be, then those are narratives that should be remembered. You have to judge these things on a case-by-case basis. You can’t make memory a sacred task.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: In a recent article in the Guardian, you referred to the Edict of Nantes, issued by Henry IV in 1598 to bring an end to the wars of religion in France. Essentially, the edict decreed that in all of the preceding troubles the memory will remain extinguished and [LAUGHS] treated as something that did not take place. Rather Soviet, it seems, that formulation. [LAUGHS] Do you think that could have worked? Can you enforce forgetting a boundary inside your own head?

DAVID RIEFF: Collective memory is not individual memory. There's no such thing, in neurological terms, as collective memory.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm.

DAVID RIEFF: So if collective memory becomes the story we tell ourselves about the past then, of course, we can forget. People are engaged in what the philosopher Nietzsche called “active forgetting” in their private lives, a lot. I don't see why there’s any reason to say that's impossible in the public life. Whether it's desirable, sometimes it is and sometimes it is not. Collective memory has been used often as a weapon and I think, you know, it might be, at certain moments, better to disarm.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: David, thank you very much.

DAVID RIEFF: Thanks for having me on.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: David Rieff is the author of In Praise of Forgetting: Historical Memory and its Ironies, and we spoke to him in May.

Mark Twain once said, “A clear conscience is the sure sign of a bad memory.” But memory always fails because every time we remember, we forget a little, like an image too often photocopied, and we fill in the blanks with unconscious ink. Some suggest that memory's failure to provide exact replicas of experience may actually be wired in, that, as Brian Boyd wrote, “Our tendency to extract and recombine and reassemble allows us to simulate or imagine or ‘pre-experience’ events that are enabling us to cope with the future,” which offers a novel take on Santayana's famous phrase, because those who too precisely remember the past may not be condemned to repeat it but they'll be less prepared for what's coming around the bend. [MUSIC] Weird, right?

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

BOB GARFIELD: That’s it for this week’s show. On The Media is produced by Meara Sharma, Alana Casanova-Burgess, Jesse Brenneman and Paige Cowett. We had more help from Micah Loewinger, Sara Qari and Leah Feder. And our show was edited – by Brooke. Our technical director is Jennifer Munson. Our engineer this week was Casey Holford.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Katya Rogers is our executive producer. Jim Schachter is WNYC’s vice-president for news. On the Media is a production of WNYC Studios. I’m Brooke Gladstone.

BOB GARFIELD: And I’m Bob Garfield.

[FUNDING CREDITS]