Polling & Democracy: An Uneasy Relationship

BOB GARFIELD: This is On the Media. I’m Bob Garfield.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And I’m Brooke Gladstone. In the race to predict who’s on top in this election season, the media will be awash in polls. Back in December, with our election season partners, FiveThirtyEight, we issued a Breaking News Consumer's Handbook: Election Polls Edition. It was directed toward primary election coverage but some of the points still bear repeating, like this one: Look for polls of likely voters, not just registered voters. Also, beware polls tagged “bombshells” or “stunners”. Outliers are usually wrong. And our favorite, asking people about their votes if the election were tomorrow, is designed to heighten drama by reducing undecided responses.

BOB GARFIELD: In theory, polls tell us the pulse of the country. They measure public support for political initiatives and they keep politicians answerable to their constituents, don’t they? According to The New Yorker’s Jill Lepore, not so much. In her 2015 article titled, “Politics and the New Machine,” Lepore retraces the often sorry history of polling in America.

JILL LEPORE: The word “poll” means the top of your head, like at the crown of your head. And you can find it in Hamlet, where Ophelia says of Polonius, “He has a beard as white as snow, all flaxen was his poll.” Before the rise of the paper ballot, people always voted in person. Like, you’d go to the town hall, someone would stand up, you know, on a tree trunk or something and look across the crowd and count the polls, count the tops of the heads of the people on one side of the town common or the other. So that place came to be called “the polls” [LAUGHS] where you’d go to have your polls counted.

BOB GARFIELD: And then pollster was?

JILL LEPORE: The word “pollster” is coined in 1939. It’s applied to George Gallop by Time Magazine, which calls him a pollster. It’s a bit of an homage to the great word “huckster.” It was a time when people were really suspicious of polls. It was a new thing and Congress was repeatedly calling for investigations of the industry, really concerned about its role in electoral politics.

We've come to accept polls as if this was a necessary piece of our electoral process but, of course, before then that really was not the case. We had a kind of healthy criticism at the time that, that they we, I think, have since lost.

BOB GARFIELD: Polls have long since gone beyond their original purpose, pre-election polls that is, which was to track how various candidates are faring. Then I wonder if you could just list the ways in which polls have become so part of the process?

JILL LEPORE: They drive donors. They determine messages. They determine clout. They determine who can run. Since the first presidential election season, where polls have been used to decide who gets to be on the main stage in a debate or where people stand on stage, there’s just more polls. [LAUGHS]

There’s just - every news story seems to need a poll to have any foundation.

BOB GARFIELD: All of that is fine, assuming [LAUGHS] that poll data really reflect public opinion. But for many reasons that you enumerate in your piece, polling doesn't necessarily accurately reflect anything. Why?

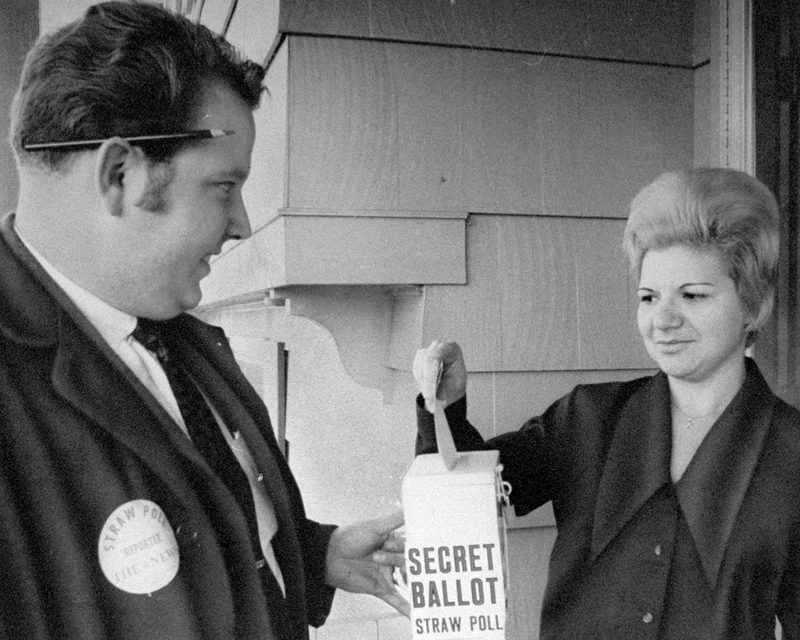

JILL LEPORE: In 1935, when George Gallup founded the American Institute of Public Opinion, he sent people door-to-door and talked to people for maybe about 45 minutes, and the response rate, that is the percentage of people who were asked, who actually answered those questions when someone knocked at the door, was well above 90, like 95, 96%. People were thrilled that someone came to their door and asked them what they thought.

Now, a response rate of [LAUGHS] 3% is a not uncommon response rate. So even if you set aside all the other problems with polls, when only 3% of the people that you ask questions to reply, the idea that what you're getting is a statistically representative sample of the electorate is very difficult to defend.

BOB GARFIELD: There's another problem that you discuss, and that is that [LAUGHS] the process itself influences opinion.

JILL LEPORE: It’s fascinating. There’s a whole very sophisticated literature that political scientists have been developing for decades on the many methodological problems of public opinion measurement. So, one is this phenomenon of forced opinion. I ask you, do you favor the Smead Will Hartley Act [?] and you say yes, even though you don't even know what it is. [LAUGHS] Or I ask you a leading question about that and you say yes.

There’s also the problem of non-opinion. So many pollsters, if you say, I don't know, even if “I don't know” isn’t an option, when they report, their findings won't report the percentage of respondents who said “I don't know.”

BOB GARFIELD: One of the presumptions of polling is that it helps political leaders understand the jaws of consent, how much leeway they have to think independently versus what they owe their constituencies to represent them in Congress or wherever. But the nature of polling, particularly in elections, is that it mainly concerns itself with those likely to vote, which limits the politicians’ understanding of what people want to those who are willing to go the ballot box. It, it disenfranchises some percentage of the population?

JILL LEPORE: Yeah, and here’s where, I mean, if you think back to the 1930s when Gallup was developing this tool, he argued that public opinion measurement was the best thing for democracy, really since the secret ballot, because instead of learning the will of the people every two years when it came around time to vote, we, the American public, could understand the will of the people every day. Candidates could, therefore, be more responsive. The premise of that, though, would seem to be, and Gallop certainly would have said this at the time, and did, that the people whose views are represented in the public opinion survey should be a representative [LAUGHS] sample of the American electorate. And there’s where the sampling methods really matter a great deal.

In practice, though, in order for not the surveys, that is, they’re asking people their questions – they’re asking people questions about their political beliefs and attitudes by asking people who they’re going to vote for - in order to make polls accurate predictions, you really only want to count the opinions of people who are going to turn out to vote. So Gallup worked by a quota system, and he just basically determined that since blacks in the South were prevented from voting, that he would have no Negro quota in any of the southern states and he just didn't ask black men and women how they would vote. So those polls that Gallup invented and used to measure the pulse of the American people actually only exacerbated the problems of disenfranchisement that were already weakening the democracy.

BOB GARFIELD: You can argue that politicians should be keeping their finger on the pulse of the electorate and you can argue that the public deserves to know what everybody else in the body politic is thinking about a, a given subject, but the, the larger philosophical questions are, do polls seek the answers for something that doesn't even exist, namely public opinion itself?

JILL LEPORE: Gallup was an ex-academic. He had gotten a PhD in applied psychology. He founded his institute at Princeton, so that the Gallup institution would have Princeton as its byline and would seem to be an academic endeavor. But social scientists, from the start, were extremely skeptical of the work that Gallup was doing because is, is the opinion of the public or individual opinions in aggregate given equal weight, that are taken in an instant as a snapshot, is – that it’s actually not really defensible as a matter of social science.

In 1948, right after Gallup said, you know, just watch, we’ll get this election right and then, you know, he predicted that Dewey would beat Truman and, I mean, he was famously wrong. And E.B. White, writing in The New Yorker a few days later, said, well, you know, it may, it may be possible to take the pulse of the American people, but you can’t always be sure that the American people haven't just run up a flight of stairs.

BOB GARFIELD: [LAUGHS] There's another actor in all of this, and that's the media. We’re sort of accessories after the fact to the very kind of distortion that you're writing about.

JILL LEPORE: I would quibble a little with your characterization of the press as accessories after the fact. I think the press is really the culprit here. I mean, Gallup, he was just selling a product to newspapers. He then started predicting elections just to prove that his surveys were accurate. It turned out, hey, wow, readers love these election [LAUGHS] predictions. Let’s do more of them. It then became really thrilling for candidates, like, oh wow, we can hire these polling firms to tell us about our candidate’s chances. And this is this really important turning point in 1972, when news organizations began conducting their own polls.

The press has actually not been reporting news but is creating news. Gallup, himself, then came to regret this. In 1972, Congress debated a Truth in Polling Act and Gallup was sort of like, okay, you know, please, reform the industry, since [LAUGHS] we’ve been taken over by a bunch of people that don't actually care about accuracy the way that I do.

BOB GARFIELD: We have an arrangement at On the Media with FiveThirtyEight for the course of this election cycle, and they made a name for themselves with a methodology for aggregating poll results in a way that favors accurate polls and subordinates inaccurate ones. But you kind of took a shot at them in your piece. You said it's a patch, not a solution.

JILL LEPORE: I mean, I’m full of admiration for that work but there are two problems. One is that good polls drive bad polls. The more unreliable polls have become, the more we rely on them. So the idea that you could sort of just say, this poll’s good, this poll’s bad and, therefore, then we’ve washed our hands of the problem is a bit of a fallacy.

I mean, the other thing that’s really worth noting is that other countries have laws and requirements about the non-conducting of polls this far in advance of election because the way in which they interfere with the democratic process has been demonstrated. It’s incredibly helpful to say, hey, this poll is known to be reliable and this poll is known to be unreliable and let's make a prediction based on weighting the reliable one disproportionately. But it skirts the broader questions about how we choose to govern ourselves.

BOB GARFIELD: I have one more question for you and it concerns, naturally, Donald Trump. Has the polling culture, and particularly the way the press depends on it, created this monster?

JILL LEPORE: I think it would be fair to say that Trump is a creature of the polls. One upside here is that for all the many occasions in which quite thoughtful people have issued quite thoughtful critiques of the polling industry and asked the American people to wonder whether this is, in fact, corrosive of our democracy, manufacturing divides that don't exist, rather than reflecting something, that the kind of uncanny rise of Donald Trump might be an occasion to actually get a little more attention to that set of critiques.

BOB GARFIELD: Yeah. Is that going to happen?

JILL LEPORE: Do I think that can happen? No, no [LAUGHS] no, no.

BOB GARFIELD: Jill, thanks very much.

JILL LEPORE: Hey, thanks so much.

BOB GARFIELD: Jill Lepore teaches at Harvard and is a staff writer for The New Yorker where she wrote, “Politics and the New Machine.”