Polling & Democracy: An Uneasy Relationship

********* THIS IS A RUSHED, UNEDITED TRANSCRIPT *********

BOB: We do love polls. It’s true. It’s fun to crow when our team is winning, and even to fume when it’s not. But they’re more than just entertainment. In theory they tell us the pulse of the country; they measure public support for political initiatives; they keep politicians answerable to their constituents. Don’t they? According to the New Yorker’s Jill Lepore, not so much. In her recent article titled, “Politics and the New Machine,” Lepore retraces the often sorry history of polling in America..

LEPORE: The word poll means the top of your head, like the crown of your head. You can find it in Hamlet where Ophelia says of Polonius "he has a beard as white as snow, all flaxen was his poll." Before the rise of the paper ballot, people always voted in person, like you'd go to the town hall, someone would stand up on a tree trunk or something and look across the crowd and count the polls, count the tops of the head of the people on one side of the town common or the other. So that place came to be called the polls. [laughs] where you would go to have your polls counted.

BOB: And then pollster was --

LEPORE: The word pollster was coined in 1939 it's applied to George Gallup by Time magazine, calls him a pollster. It's a bit of an homage to the great word huckster. It was a time when people were really suspicious of polls, it was a new thing, and congress was repeatedly calling for investigations the industry, really concerned about its role in electoral politics. We've come to accept polls as if this was a necessary piece of our electoral process, but of course before then that was really not the case. We had a kind of healthy criticism at the time that we have I think since lost.

BOB: Polls have long since gone beyond their original purpose, pre election polls that is, which was to track how various candidates are faring and I wonder if you could just list the ways in which polls have become so part of the process.

LEPORE: They drive donors, they determine messages, they determine clout, they determine clout they determine who can run. This is the first presidential election season where polls have been used to decide who gets to be on the main stage in a debate, or where people stand on stage. There's just more polls! Every news story seems to need a poll to have any kind of foundation.

BOB: All of that is fine, assuming that poll data really reflect public opinion, but for many reasons that you enumerate in your piece, polling doesn't necessarily accurately reflect anything. Why?

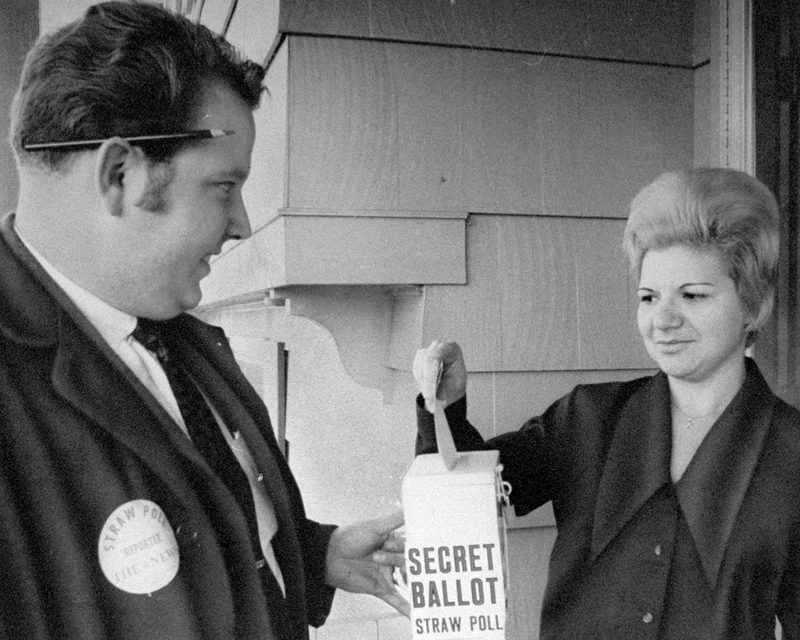

LEPORE: In 1935 when George Gallup founded the American Institute of Public Opinion, he sent people door to door and talked to people for maybe about 45 minutes. And the response rate that is the percentage that were asked that actually answered those questions when someone knocked at their door, was well above 90, like 95, 96 percent. people were thrilled that someone came to their door and asked them what they thought. Now, the response rate of 3% is a not uncommon response rate. So even if you set aside all the other problems with polls, when only 3% of the people that you ask questions to reply, the idea that what you're getting is a statistically representative sample of the electorate is very difficult to defend.

BOB: There's another problem that you discuss and that is that the process itself influences opinion.

LEPORE: It's fascinating, there's a whole very sophisticated literature that political scientists have been developing for decades on the many methodological problems of public opinion measurement. So one is this phenomenon of forced opinion. I ask you do you favor the Speedwell Hartley Act, and you say yes even though you don't know what it is. [laughs] Or I ask you a leading question about that and you say yes. There's also the problem of non opinions, so many pollsters if you say i don't know, even if "i don't know" isn't an opinion, when they report their findings won't report the percentage of respondents who said I don't know.

BOB: One of the presumptions of polling is that it helps political leaders understand the jaws of consent. How much leeway they have to think independently, versus what they owe their constituencies to represent them in Congress or wherever. But the nature of polling particularly in elections, is that it mainly concerns itself with those likely to vote. Which limits the politician's understanding of what people to those who are willing to go to the ballot box. It disenfranchises some percentage of the population.

LEPORE: Yeah, and here's where I mean if you think back to the 1930s when Gallup was developing this tool, he argued that public opinion measurement was the best thing for democracy really since the secret ballot because instead of learning the will of hte people every two years when it came around time to vote, we the American public could understand the will of the people every day. Candidates could therefore be more responsive. The premise of that though would seem to be and Gallup certainly would have said this at the time and did, that the people whose views are represented in the public opinion should be a representative sample of the American electorate, and that's where the sampling methods really matter a great deal. In practice, though, in order for not the surveys, that is asking people, they're asking people questions about their political beliefs and attitudes by asking people who they're gonna vote for, in order to make polls accurate predictions, you really only want to count the opinions of people who are going to turn out to vote. So Gallup worked by a quota system, and he just basically determined that since blacks in the south were prevented from voting, that he would have no negro quota in any of the southern states and he just didn't ask black men and women how they would vote. So those polls that Gallup invented and used to measure the pulse of the American people, actually only exacerbated the problems of disenfranchisement that were already weakening the democracy.

BOB: You can argue that politicians should be keeping their finger on the pulse of the electorate, and you can argue that the public deserves to know what everybody else in the body politic is thinking about a given subject. But the larger philosophical questions are do polls seek the answers for something that doesn't even exist, namely, public opinion itself.

LEPORE: Gallup was an ex academic, he had gotten a PhD in applied psychology, he founded his institute at Princeton so that the Gallup Institution would have Princeton as its byline and would seem to be an academic endeavor, but social scientists from the start were extremely skeptical of the work that Gallup was doing because is the opinion of the public our individual opinions in aggregate given equal weight that would taken at an instant as a snapshot? There's actually not really defensible as a matter of social science. In 1948 right after Gallup said you know, just watch, we'll get this election right and then he predicted that Dewey would beat Truman and he was famously wrong, and EB White writing the New Yorker a few days later said, well you know, it may be possible to take the pulse of the American people but you can't always be sure that the American people haven't just run up a flight of stairs.

BOB: [Laughs] There's another actor in all of this, and that's the media. We're sort of accessories after the fact to the very kind of distortion that you're writing about.

LEPORE: I would quibble a little with your characterization of the press as accessories after the fact, I think the press is really the culprit here. I mean Gallup he was just selling a product to newspapers. He then started predicting elections to prove that his surveys were accurate. Turned out, hey wow! Readers love these election predictions! Let's do more of them! It then became really thrilling for candidates, oh well we could hire these polling firms to tell us about our candidates' chances and this is this really important turning point in 1972 when news organizations began conducting their own polls. The press is actually not then reporting news but is then creating news. Gallup himself came to regret this in 1972 Congress debated a truth in polling act. And Gallup was sort of like, please, reform the industry, it's been taken over by a bunch of people that don't actually care about accuracy in the way that I do.

BOB: We have an arrangement at On the Media with Fivethirtyeight over the course of this election cycle. And they made a name for themselves with a methodology for aggregating poll results in a way that favors accurate polls and subordinates inaccurate ones. But you kind of took a shot at them in your piece, you said it's a patch not a solution.

LEPORE: I mean I'm full of admiration for that work, but there are two problems: one is that good polls drive bad polls. The more unreliable polls have become the more we rely on them. So, the idea that you could sort of just say this poll's good, this poll's bad and therefore we've watched our hands of the problem is a bit of a fallacy. And the other thing that's really worth noting is that other countries have laws and requirements about the non conducting of polls this far in advance of election because the way in which they interfere with the democratic process has been demonstrated. It's incredibly helpful to say, Hey, this poll's known to be reliable and this poll is known to be unreliable, and let's make a prediction based on weighting the reliable one disproportionately, but it skirts the broader questions about how we choose to govern ourselves.

BOB: I have one more question for you. And it concerns naturally Donald Trump. Has the polling culture, and particularly the way the press depends on it, created this monster?

LEPORE: I think it would be fair to say that Trump is a creature of the polls. One upside here is that for all the many occasions in which quite thoughtful people have issue quite thoughtful critiques of the polling industry and asked the American people to wonder whether this is in fact corrosive of our democracy, manufacturing divides that don't exist, rather than reflecting something, that the uncanny rise of Donald Trump might be an occasion to actually get a little more attention to that set of critiques.

BOB: Yeah is that gonna happen?

LEPORE: Do I think that can happen? No. [laughs] No.

BOB: Jill thanks very much.

LEPORE: Hey thanks so much.

BOB: Jill Lepore teaches at Harvard and is a staff writer for a New Yorker, where she wrote "Politics and the New Machine."

BROOKE: Coming up, the Paris talks. What did they mean? What did we report? What do you care, it’s not about ISIS.

BOB: This is On the Media.