The Pandemic Words We're Still Getting Wrong

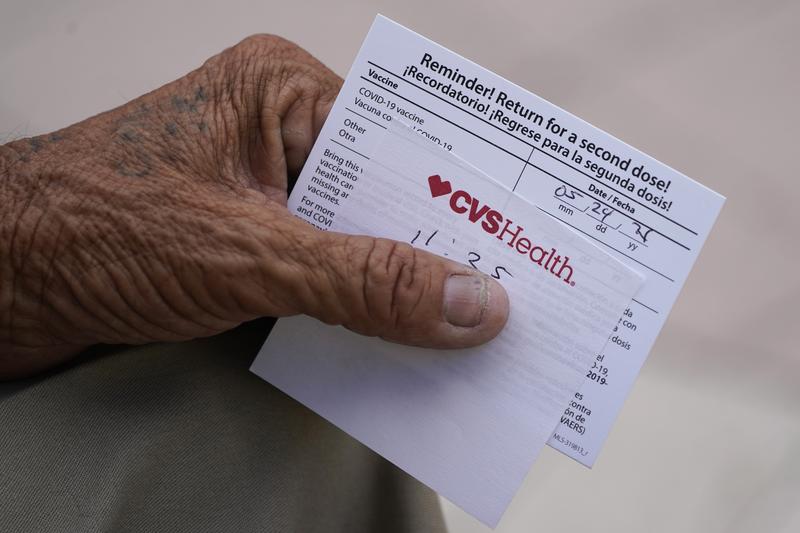

( Wilfredo Lee / AP Photo )

BROOKE GLADSTONE From WNYC in New York, this is On the Media, I'm Brooke Gladstone. This week, the FDA authorized booster doses of Moderna and Johnson & Johnson vaccines. This follows the agency's approval of additional shots of the Pfizer vaccine back in August.

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT The FDA says no matter what COVID 19 vaccine you initially received, your booster can be whichever one you choose. A recent study found a small pool of J & J recipients saw a 76 fold increase in antibodies with Moderna, a 35 fold increase with Pfizer and just a fourfold increase with J & J. [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE The term booster is just one example of a term that's crossed over from the medical lexicon into the mouths of us non-specialists. Eager to embrace language that clarifies the COVID risk we face. Nowadays, we casually refer to COVID-19 tests, to asymptomatic COVID cases and to the fully-vaccinated, but those usages are not precisely right. Take the word quarantine.

KATHERINE J WU I still see every single week without fail someone saying so-and-so has tested positive and they are going into quarantine. They're not going into quarantine, they're going into isolation.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Katherine J. Wu is a staff writer at The Atlantic, where she covers science. She wrote recently about the long list of words that still, almost no one gets right. Welcome to the show, Katherine.

KATHERINE J WU Thank you for having me. It's great to be here.

BROOKE GLADSTONE In your reporting, you've tracked something you call linguistic leakage, which makes me think of Inigo Montoya. The words don't mean what you think they mean. How does linguistic leakage occur?

KATHERINE J WU Yes, I'm very glad you brought in the Princess Bride reference early. You know, when a word starts off and gains traction in one community, but it's generally pretty siloed off into that community, and then it rapidly moves into another community or into the public at large, but the context doesn't necessarily follow.

BROOKE GLADSTONE In a recent article, you took on booster shots. Where did that term even come from?

KATHERINE J WU This was just something that people used to talk about. Oh, this is something better and improve it, something that takes us up. Something that lifts us.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Booster seat.

KATHERINE J WU Mmhmm.

BROOKE GLADSTONE If somebody is a real booster of a project, they're trying to support it. It always had really good connotations.

KATHERINE J WU Yeah. And when this did migrate into vaccine lexicon, I imagine that made the word quite appealing. You know, who doesn't want to boost their immunity? That sounds great. And Elena Conis at UC Berkeley, who's a medical historian, said she thinks that using words like Booster might have helped public health experts and scientists make additional shots of vaccines that needed them more appealing to the public, like come get your boots. Doesn't that sound amazing?

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT Encouraging developments in the U.S. There's been an unprecedented demand for COVID booster shots in recent days. More than seven million people have gotten an extra dose of vaccine so far. [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE But you say that this perky optimism actually obscures what those shots do.

KATHERINE J WU Boosters are not just this unilateral resource, and all the effects are additive, and we can just keep stockpiling protection like toilet paper or dried beans. I added this idea into my piece that maybe boosters would better be described as reminder shots. And here I took some inspiration from what some other languages have done, which I find really fascinating. Spanish speakers sometimes refer to booster shots as refuerzo, which is a term that sort of talks about reinforcement. People who speak Italian say richiamo, which I realize I've never said that word out loud, so maybe that's wrong.

BROOKE GLADSTONE [LAUGHS] sounds right!

KATHERINE J WU And the French say repel. And both of those words signify recollection like a refresher course, something that has been seen before but maybe hasn't been seen for a while. And maybe the body's gotten a little forgetful, and so a booster shot is, 'Oh, I've seen this before, I should still be paying attention to this. This is still relevant,' which is really what a booster shot is supposed to do. It's trying to rescue a response that scientists think has declined over time. Maybe your immune cells have gotten a touch of amnesia. They are no longer taking the coronavirus as seriously, and this is just a way to sort of juice them back up, bring them back to where they were before. That is the primary goal.

BROOKE GLADSTONE You've also said that the framing of the booster shot as a reminder shot or replenishing could be more of a clear eyed way to assess global equity. Boosters by default, top off resources that have already been given.

KATHERINE J WU And I think boosters may not really be that urgent of a situation, especially knowing that we have, on a global scale, a limited supply of vaccines and knowing that we still have so many countries around the world, especially those that are considered lower income countries where most people have not even had the opportunity to get their first dose of a vaccine. It feels a little bit like inviting people for third helpings at a buffet line when some people are still starving outside the restaurant.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Currently, there's a debate over whether a second shot of the Johnson and Johnson vaccine, which was billed as a single shot, should even be described as a booster that I think, Dr. Fauci said. It probably should have been a double shot to begin with.

KATHERINE J WU If we're talking about boosters as something that is replenishing something that has been lost. That's two criteria. First, you have to see loss and then you have to see what was lost being replenished. And it's not totally clear that a second shot of the Johnson and Johnson vaccine would be fulfilling both those criteria. It does seem that people who got the Johnson and Johnson vaccine, they've certainly been well protected for many months, but they might have started out at a kind of lower level of protection than people who got one of the many vaccines the Moderna or Pfizer vaccines. And yet that level has held quite steady over time. So we're actually not seeing very much waning in protection after people get the Johnson and Johnson vaccine. So that criterion seems a little shaky. But if we did add a second dose, what the researchers are seeing is that this baseline level of protection goes up. And so that may be better described as just a straight up second dose. And the idea there is you need two shots to be full up to sort of reach full production to begin with

BROOKE GLADSTONE Another term: fully-vaccinated. What's the definition of being fully vaccinated?

KATHERINE J WU This is an especially important question to be asking now that boosters are rolling out. A lot of people have been confused about whether they are still considered fully vaccinated if they haven't gotten their boosters yet. The short answer is yes. So what is full vaccination? As the CDC is defining it, you are fully vaccinated two weeks after you get the final vaccine dose in a primary series. And the primary series is, for Moderna and Pfizer, those two initial shots of mRNA spaced either three or four weeks apart. And for Johnson and Johnson, for now, it is that single shot - two weeks after that,

BROOKE GLADSTONE Although maybe it should have been two...

KATHERINE J WU Who knows? Honestly, that definition could change by next week. We'll see.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Let's talk about another one. Natural immunity has been weaponized to imply that vaccines are unnatural and thus unsafe. Here's a clip from Fox News.

[CLIP]

FOX NEWS Well, it's amazing. Out of hundreds of speeches and hundreds of hours of interviews, a complete absence of any mention of natural immunity disenfranchising a large portion of the unvaccinated natural immunity. [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE That's what happens when you have had COVID 19 and you have some antibodies, right?

KATHERINE J WU It's the immunity that manifests itself after you have been "naturally infected" by an actual microbe, a virus, a bacterium, a parasite, or whatever. And that is supposed to be in contrast to the immunity that occurs after you've been vaccinated, which of course, does not involve an actual virus.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Mm-Hmm.

KATHERINE J WU But oh gosh, this one caught me off guard during the pandemic, honestly. I've seen this term very often. I never really thought twice about it. But during this pandemic, I've seen many people say 'I have natural immunity. I shouldn't be getting vaccinated' or natural immunity is superior to post-vaccination immunity. And I think what's interesting to think about here is what the term natural has been leveraged for. You know, we see this as a very positive thing, like it sounds organic, it sounds appealing, it sounds healthy, and it also casts the alternative as unnatural. It makes vaccines sound artificial or unhealthy, and that's absolutely not the case.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Inoculation is an attempt to create what natural immunity would do in a safe environment where you don't actually have to get sick in order to develop those antibodies, right?

KATHERINE J WU Vaccines are a safe mimic of these triggers for protection and what could be better than that? It's like having your cake and eating it, too.

BROOKE GLADSTONE So we've talked about words which carry, to their detriment at times, positive associations like booster or natural immunity, but what about words that the public has come to interpret as really negative, unduly negative – like breakthrough infections.

KATHERINE J WU This is another interesting word where there has long been a sort of research vaccine specific connotation to breakthrough. But there's also been a colloquial one, like think of the way that we talked about breakthroughs in 2019. It was like, ‘oh, scientists make a breakthrough in cancer research.’ It sounded great. And honestly, in the past few months, it has become almost synonymous with vaccine failure, which should not be the case, but that's certainly the narrative that has been built around it.

BROOKE GLADSTONE But isn't it vaccine failure?

KATHERINE J WU All you have to do to qualify as a breakthrough case is test positive for SARS-CoV-2, this new coronavirus, more than two weeks after you have gotten your final dose and vaccine regimen. You have to test positive despite being fully vaccinated. But that seems a little weird, right? Because a positive test is not necessarily trivial, but it is also just a positive test. Our vaccines were designed to block disease, especially severe disease. And that's really just a subset of positive tests.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Exactly. So if you aren't sick and if you happen to have the SARS-CoV-2 virus which causes COVID, that doesn't mean you have COVID. If this were an SAT question, SARS-CoV-2 is to COVID as HIV is to AIDS.

KATHERINE J WU Yes, I think that is a fair comparison of words. Yeah.

BROOKE GLADSTONE And in fact, that's something else that drives you a little bit nuts that they're called COVID tests. When you're really just taking a SARS-CoV-2 test to see if you're carrying it?

KATHERINE J WU Exactly. And I think this is a really important distinction because oftentimes people say, Oh, someone had a breakthrough, how unfortunate that they had COVID. But that's not necessarily the case, because again, breakthrough is a positive test. It means something detected a piece of the virus somewhere in your body, and a test alone can't really distinguish between, Oh, this was full blown, symptomatic COVID 19 or a different case, which was actually, in my view, potentially a very optimistic scenario in which you as a vaccinated person or may be exposed to this virus. It got into your nose a little bit, but your vaccinated immune system was immediately alerted to the presence of the virus and thought, OK, I'm going to take care of this really fast. We're going to destroy all these viral particles so quickly that this person never even gets sick. That sounds wonderful to me.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Yeah, when we talk about words being misused or clouding our collective comprehension of the pandemic, who can we blame? Or is the confusion a team effort?

KATHERINE J WU We don't necessarily need to assign blame. This is an incredibly confusing time, but the faults certainly does not lie with a single party. And I think there are things that we can all do to sort of improve what has been an ongoing communications nightmare since almost day one of this pandemic. I would love to see it if experts, when they're sort of introducing new terms, would just make sure to be really clear about context. You know, you might have heard this word in a colloquial context, but here is what we have used it to mean in science. And here's how those things differ. It would also be great if you know myself and my colleagues, as reporters, as journalists, as writers, we're just really careful about how we use these words, not mixing them up so that we're not implying that certain things are better or worse than they actually are. And I would love it if the public would be open minded to the idea that, you know, definitions can sometimes start out very squishy. That words sometimes have a very difficult time migrating from one field to another.

BROOKE GLADSTONE You've said it's hard to unring a linguistic bell after it's been rung?

KATHERINE J WU Yeah. And I think that's what's key here, right? After we sort of develop an association to a word, it's pretty hard to unlearn it. But right now, especially when we are dealing with something that is so colossal and so high stakes and so unknown, I think we all have to be ready to unlearn some things and learn some very new things that we might not have expected.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Katherine, thank you so much.

KATHERINE J WU Thank you for having me. This was really fun.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Katherine J. Wu is a staff writer at The Atlantic, where she covers science. Coming up, something you need to know about every medical advance or intervention: you have to bet your life to save it. This is On the Media.