Our Shakespeare, Ourselves

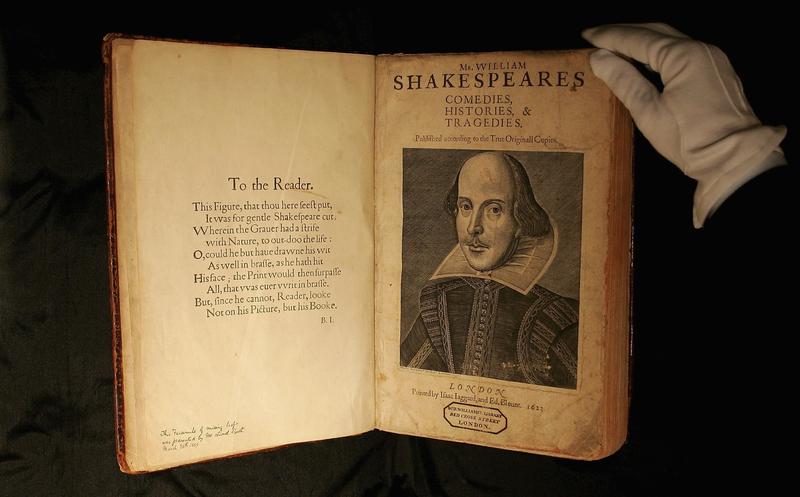

( Scott Barbour / Getty )

BROOKE GLADSTONE: From WNYC in New York, this is On the Media. Bob Garfield is away this week. I’m Brooke Gladstone.

[SOUND OF STARLINGS/UP & UNDER]

And these are – starlings.

The US is infested with starlings because of Shakespeare. On a snowy March morning in 1898, a Bard- and bird-loving drug maker named Eugene Schieffelin released 60 starlings, because they’d once been mentioned by Shakespeare, in Central Park. There are now some 200 million of them larding our homeland with guano. As the Bard once said, “A pestilence hangs in our air.”

Then again, you might say the same about him, depending on your first encounter. A recent unscientific survey taken in Manhattan’s Washington Square Park suggests that, for some, Shakespeare was snuffed by pedagogy's cold dead hand.

[OUTDOOR SOUNDS]

BROOKE GLADSTONE (Q): Any personal experience?

WOMAN: High school, having to read it all the time and not really understanding the language.

WOMAN: I, I appreciate his work, however, I don’t feel as if I connected to it now.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: But we met a bunch of, I’m guessing, fourth graders who saw it differently.

CHILD: Plays.

CHILD: Poetry. [LAUGHS]

[LAUGHTER]

CHILD: Happiness.

CHILD: Old people.

[CHILDREN’S LAUGHTER]

CHILD: Happy.

CHILD: I’m Awesome.

BROOKE GLADSTONE (Q): Can you quote any?

CHILD: No.

[BOTH SPEAK/OVERLAP]

CHILD: She might be small but she’s fierce.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: That’s from “Midsummer,” I think.

CHILD: That’s on my shirt.

CHILD: That’s off her shirt. [LAUGHS]

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: In fact, some educators believe that high school is already too late to meet the Bard. Students are too self-conscious to ask for the meanings of words and phrases and, with college looming, they’re too worried about grades. So when’s the right time?

We’d argue, right now. It’s his 400th death day and, even if it’s all Greek to you – his phrase – even if he sets your teeth on edge – also his – he is in your mouth. As the great British journalist Bernard Levin once noted, if you’ve ever played fast and loose or refused to budge an inch, believed the game is up or that the truth will out, ever been tongue-tied or hoodwinked, made a virtue of necessity or seen better days, had too much of a good thing, lived in a fool’s paradise or given the devil his due, even if you bid me good riddance, but me no buts, for you are quoting Shakespeare.

But why Shakespeare? What and, especially, who? The answers to those questions are swallowed in confusion - his phrase.

PROF. JAMES SHAPIRO: I was visiting a school on the Upper West side, talking to fourth-graders about Shakespeare's Sonnets.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: That’s Columbia Professor James Schapiro, author of many books about Shakespeare and his times.

PROF. JAMES SHAPIRO: One of the kids raised his hand and said, my big brother told me that Shakespeare didn't write “Romeo and Juliet,” is that true?

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

And it was one of those moments of reckoning. It wasn't a situation in which I could muster up my professorial authority, like I do in my Columbia classrooms, and say, that's rubbish and I'll fail you if you ask that question again.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Now, at this point, some listeners, those who take the view that the man we know as Shakespeare did not actually write the works attributed to him, will be tempted, as someone once wrote, to “cry havoc and let slip the dogs of war.” And it’s true that Professor Shapiro, like most of his colleagues in academe, believe the man from Stratford is, in fact, the author. But we won't fix on resolving that question. We’re far more interested in the way that war has been waged across centuries.

PROF. JAMES SHAPIRO: There are people who think that Francis Bacon wrote the plays, the Earl of Oxford wrote the plays. There are 70 other candidates for the plays.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Professor Shapiro will serve as my Virgil for the hour.

PROF. JAMES SHAPIRO: What became interesting to me was not what people thought but why they thought it. And it turns out some of the smartest people – Mark Twain, Sigmund Freud, Henry James, Helen Keller, it's a long list - join this company of Shakespeare deniers who, for really complicated and very interesting and sometime sad reasons, had to deny his authorship.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: But it does start with the fact there's very little documentary evidence about Shakespeare.

PROF. JAMES SHAPIRO: There’s more about Shakespeare than about almost any other Englishman from his days –

[BOTH SPEAK/OVERLAP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Is that true?

PROF. JAMES SHAPIRO: - who had the kind of life that he did. Absolutely. We just don't have a lot of records because four centuries later those records don't survive. And the records that do survive, official documents - real estate, marriage, death, baptism - those are the kind of things that were recorded. The kind of things we actually wanted to know about Shakespeare today – who did he sleep with, what were his political views, was he cozy with Queen Elizabeth or King James - those are not the sorts of –

[BOTH SPEAK/OVERLAP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Did he like his wife?

PROF. JAMES SHAPIRO: What do we do with that second-best bed he left?

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

Or was that the good bed, the bed that couldn’t be brought downstairs? I mean, what’s that about?

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

So we don’t have answers to those questions, and they’re really the kind of questions we want answers to.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Right, and Shakespeare, the artist, didn’t seem to square with Shakespeare of these documents, Shakespeare who wrote the will or Shakespeare who brought people to court to get his loans paid back.

PROF. JAMES SHAPIRO: There are two issues, really, here. One is the discrepancy between those official documents and the romantic Shakespeare that we want to know about or the political Shakespeare. The problem is that we also project back onto Shakespeare certain assumptions about his age that are not true. The whole notion of literature as autobiographical, as self-expression was not Shakespeare's culture. And if we are trying to shoehorn Shakespeare into a confessional writer, about his sexual life, about his religious beliefs we’re not going to get close to who the man was.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: But in every generation, we crave connection. In 1794, a local doctor wrote in his diary that he’d wrested Shakespeare's skull from his grave because skulls held secrets, and also to win a hefty bet made by politician and author Horace Walpole. But only last month did radar reveal that he may have succeeded.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

FEMALE CORRESPONDENT: Archaeologists who recently scanned the grave of William Shakespeare say they have discovered that his skull appears to be missing.

FEMALE CORRESPONDENT: Findings support the claim, first made in 1879 but long dismissed as myth, that the Bard’s skull was stolen by grave robbers in the 18th century.

MALE ACTOR: “Blessed be the man that spares these stones, and cursed be he that moves my bones.”

FEMALE CORRESPONDENT: But did he rest in peace?

BROOKE GLADSTONE: It’s presumed the skull was sought because of the belief back then that its size and shape could reveal a person's character. But you can't solve the mystery of genius by pillaging a corpse, nor can you reconcile Shakespeare's artistry with the stingy documents he left behind, nor can you find the lived reality of the man in his poems and plays.

PROF. JAMES SHAPIRO: We live in an age in which you get an MFA in writing and the first thing you're told is you have to live it to write it, from some alcoholic teacher who’s slept with half his class and is encouraging them to write about alcoholic teachers who sleep with half their class.

[BROOKE LAUGHING]

And it's not true. You don't have to go to the moon to write science fiction. You don’t have to be an animal to write Animal Farm. The truth is you have to have an imagination. It all turns on that.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: But sometimes imagination fails. Take the first great Shakespeare scholar and Irishman named Edmond Malone.

PROF. JAMES SHAPIRO: He’d cut out little bits and pieces from rare materials that passed through his hands. He wouldn't return library books.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: But it's really serious –

[BOTH SPEAK/OVERLAP]

PROF. JAMES SHAPIRO: It’s terrible.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: - because there aren’t multiple copies in those days.

PROF. JAMES SHAPIRO: He was handling things that were unique. Nobody else has ever found a letter written to Shakespeare, and he found it and he decided not to publish it. Why? Because it only showed Shakespeare involved in lending money, and he didn't want to tarnish Shakespeare's reputation in that way. So the story really gets going, you know, 1780s, 1790s, as people are trying to figure out, okay, he's the greatest writer who’s ever lived, he’s the god of our idolatry. Garrick, the great 18th-century Shakespeare actor, is creating the first Shakespeare Festival. There are now a gazillion in the world.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: How come?

PROF. JAMES SHAPIRO: The interest in Shakespeare, the man, and the interest in the plays and the ways in which the two fit together is something that each age has to wrestle with. And the answers that each age comes up with - who was this man and what does that tell us about the plays or the poems – says more about that age than it does about anything of Shakespeare himself.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Let’s talk about Edmond Malone and his method, because the greatest Shakespeare scholar, you say, of all time may have committed the original sin when he focuses on the Sonnets, and particularly Sonnet 93.

PROF. JAMES SHAPIRO: Yeah. What I really, really can't forgive is he's trying to write the great biography of Shakespeare. He knows he knows more than anyone else, and yet, he can't tell the story because too much information is lost. So Malone decided there was one great source that was going to tell him everything he needed to know, and that was The Complete Works of William Shakespeare, which he had been editing. So he comes across this sonnet which is about a man accusing his wife of adultery.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: If you’ll forgive me,

“So shall I live, supposing thou art true,

Like a deceived husband;

Unless you want to do it.

PROF. JAMES SHAPIRO: No, I love to hear it, but I need the anger of the deceived husband.

[BOTH SPEAK/OVERLAP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Okay, all right, I’ll do it again.

“So shall I live, supposing thou art true,

Like a deceived husband;

So love’s face

May still seem love to me, though altered new:

Thy looks with me, thy heart in other place.

For there can live no hatred in thine eye,

Therefore in that I cannot know thy change.”

PROF. JAMES SHAPIRO: See, you read that, you know she’s cheatin’ on him.

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

He’s livin’ in London, writin’ those plays, she’s up in Stratford doin’ who knows what with who knows whom. Right? I mean, that’s what Malone’s thinkin’. And then he says, here, I have the will. He left her the second best bed just to show her he knows she’s cheatin’ on him. All of a sudden, he’s taking this huge leap, to read the works as autobiography. And that is the original sin, and it’s the slipperiest slope that ever a scholar slid down.

Malone, for the record, couldn’t find a wife, so here’s a kind of loser guy projecting onto Shakespeare anger at woman. So this is the second half of that equation.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

The first half is yeah, Shakespeare wrote autobiographically. The second is whoever’s claiming that tends to claim that Shakespeare is just like them! Marxist Shakespeares think that Shakespeare is writing Marxist stuff, Jews think that Shakespeare is writing sympathetically to Jews. You know, you can go right down the list. And it’s something about his works that make us want to read them autobiographically and make us want to project ourselves into those works.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: But if the autobiographical details you believe you’ve found in the works don’t seem to match the man who authored them, then you must seek another man.

[CLIP]:

MICHAEL DUNN: For all anybody knows and can prove, this man never wrote a play in his life. For all anybody knows and can prove, this man never wrote a letter in his life.

[AUDIENCE LAUGHTER]

Handwriting experts have questioned whether he could write at all.

[LAUGHTER][END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: That was Michael Dunn, a faithful Oxfordian, that is, one who believes Edward de Vere, the Earl of Oxford, was the true author of Shakespeare’s canon.

Coming up, the Oxfordians, the Baconians, that is to say, the anti-Stratfordians through the ages and what their convictions say about our infinite capacity to believe or not to believe. This is On the Media.

[END SEGMENT A]

STATION BREAK ONE

* SEGMENT B *]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: This is On the Media. I’m Brooke Gladstone.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

Now it’s time for war, or revelation, depending on your point of view. First, a brisk summary of the two main points driving the Shakespeare deniers. Point 1, as we heard, no evidence. None of the existing documents connected to him can confirm that he was even educated. In fact, his handwriting was atrocious and he didn't always spell his name the same way. No records suggest the folks of Stratford ever knew him as a writer, only as a merchant, occasional tax evader, grain hoarder and litigant. Point 2, it’s just not possible. This son of a glove maker knew too much of court politics and culture, too much of foreign lands, of falconry, of law, of literary form, too much of human nature. No, this man from Stratford could not be the god of our idolatry. The so-called “Bard” was at best a beard.

But for whom? In 1850, the game is afoot, the path previously having been laid by a revolution in critical analysis and the toppling of two sorts of gods.

PROF. JAMES SHAPIRO: The first was dethroning Homer as an author.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Jim Schapiro, author of Contested Will.

PROF. JAMES SHAPIRO: Scholars come along and they’re looking at these texts and they say, well, they’re written over a couple of hundred years and either Homer lived for hundreds of years and changed his style in unbelievably irreconcilable ways or the man we call Homer is an invention.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And this basically is the beginning of higher criticism. Lower criticism is the study of textual minutiae. Higher criticism concerns a work's origins, date, mode of composition, transmission, etc.

PROF. JAMES SHAPIRO: It’s sometimes dangerous because it's one thing to knock Homer off the pedestal, but after that the next move was to knock Jesus off the pedestal by pointing out discrepancies in the Gospels. And to make this claim was heretical.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And David Strauss in 1835 argued that the Gospels’ Matthew, Mark, Luke, John couldn't have been eyewitnesses to Jesus's life, lays out a really strong case. It's so strong that a dozen years later a man named Samuel Schmucker decides to mock the whole idea.

PROF. JAMES SHAPIRO: Schmucker’s this future preacher, a young man in Pennsylvania. He is a deep believer in Jesus and he's a deep believer in Shakespeare. He's so outraged by the argument of this high criticism that's trying to challenge the legitimacy of the Gospels that he makes the argument, yeah, let’s, let’s say the same thing about Shakespeare.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: As a reductio ad absurdum.

PROF. JAMES SHAPIRO: Exactly.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: If Jesus can be taken down this way, I’ll just show you the fatuousness of this approach by using something that is absolutely untouchable.

PROF. JAMES SHAPIRO: And he didn’t know it, but he wrote the playbook for the anti-Shakespeare movement ever after.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Enter Delia Bacon, the youngest daughter of a deceased Congregationalist minister who left the family impoverished in New England. A dazzling intellect, she delivers celebrated lectures on Shakespeare at a girls’ school, but her ambition was tightly bridled by her religious family.

PROF. JAMES SHAPIRO: Hardcore Puritan, that’s the way to think of it, you know, everything but the buckles on the shoes and the cap. And she tried moving to New York and creating a life as a writer, and every time she strayed a little too far the pressure from the family pulled her back into the fold.

Delia Bacon is one of the most underrated intellectuals in American history, and the more I learned about her, the sadder the story became.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: An esteemed lecturer, now entrenched in Shakespeare, she developed a close friendship with a fellow lodger, Alexander MacWhorter, 11 years younger, a Yale divinity student. Delia thought he loved her and she wrote letters professing the same, but he did not. In fact, he read her letters out loud to amuse his friends. Yale Divinity School held a public trial to determine if he’d deceived her.

PROF. JAMES SHAPIRO: She was completely disgraced. The verdict went against her and she was unmarriageable. She fled to England just to get away. She now had a mission. She was going to prove that others, led by Francis Bacon, no relation, were responsible for writing the plays and poetry of William Shakespeare.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: It was deeply controversial, but she did have Emerson's backing.

PROF. JAMES SHAPIRO: She had Emerson's backing and –

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Hawthorne went along with it.

PROF. JAMES SHAPIRO: Hawthorne bankrolled the publication of her unreadable book. Her Shakespeare was a radical, and the group of writers around Francis Bacon responsible for the plays and poems?

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Basically a cabal of writers that were trying to overthrow the –

PROF. JAMES SHAPIRO: Tyrannical regime of Queen Elizabeth and then King James.

[CLIP]:

CORIOLANUS:

It is a purpos'd thing, and grows by plot,

To curb the will of the nobility:

Suffer't, and live with such as cannot rule

Nor ever will be rul'd.

[END CLIP]

PROF. JAMES SHAPIRO: And what she was trying to do was say, look, the received story of the foundation of all the values that Americans have, from the Pilgrims, who were religious dissenters, is not true. The true spirit of republicanism which is in this country comes from these men, Francis Bacon and his cohort, who gave us plays like “Coriolanus” and “Julius Caesar,” which are radical and time monarchical plays.

[CLIP]:

ANTONY:

I come to bury Caesar, not to praise him.

[END CLIP]

PROF. JAMES SHAPIRO: Anybody reading this at the time must have thought, oh my God, she’s trying to topple the very story of Thanksgiving, of Puritans founding the republican values that give us our government.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Did Delia Bacon go crazy?

PROF. JAMES SHAPIRO: Delia Bacon lost her sanity in the last two years of her life and a nephew came and rescued her, brought her back to the States, and she was put into a place for the insane and she died two years later. But she certainly was not insane when she came up with this idea. She was quite brilliant.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: She was the first Baconian, but there were notable others, among them Helen Keller, Walt Whitman and Mark Twain.

PROF. JAMES SHAPIRO: Mark Twain believed you could only write what you knew because he tended to write about what he knew, his days on the Mississippi, his time out in California. He was one of the great autobiographical writers. So he was convinced that whoever wrote these plays had to have lived through those experiences, and he was pretty clear Shakespeare of Stratford could not and did not do so. He was a Baconian and a committed one. Twain and Helen Keller and others are part of this late 19th, early 20th century shift.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: It was Keller who brought Twain's stunning new evidence of the Bacon theory.

PROF. JAMES SHAPIRO: This is extraordinary, a weekend up in Connecticut where Mark Twain is living, and Helen Keller goes up there with her friend and nurse who had recently married a Harvard lecturer named Macy. And Macy was a deep Shakespeare denier. And he brings with him a book which has these kind of acrostics. In other words, if you read all the way down on page 72 of the Folio –

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Take the first letter of each line, it reads FRANCISCO BACONO or, in other words, it inaugurates the great search for a cipher, a code embedded in Shakespeare that will ultimately and finally prove that it was somebody else.

PROF. JAMES SHAPIRO: And it makes great sense because this is the time where, where Morse Code is invented, ciphers are huge.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So explain to me the motivation of Twain. I mean, he said, “I have allowed myself for so many years the offensive privilege of laughing at people who believed in Shakespeare that I will perish with shame if the clergyman's book - this is the one about the cipher - fails to unseat that grossly commercial wool stapler.”

PROF. JAMES SHAPIRO: Yeah, well, you know, there’s more than a literal - literary rivalry here. I mean, Twain was the first great branded writer of our day, the white suit, the pipe. He even endorsed products. This, this was the guy who was a brand. And he had to figure, hey, when I go to my hometown of Hannibal, they’re pouring out in the streets and everybody could tell stories about me. If Shakespeare was as great as people say he was, why didn't people pour out in the streets in Stratford and write little bits? It doesn't make sense to me.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: But why choose Bacon as the hidden bard, anyway? Well, he did fit the era's model of what a genius should be, a Cambridge-educated parliamentarian and erstwhile Lord Chancellor, author of literary, legal and religious works, proclaimed by some “the father of the scientific method.” Later, he was disgraced for taking bribes and his poetry apparently stunk but viewed through the right lens, he was a master of obscure arts, a principled though thwarted power, a veritable Prospero.

[CLIP FROM “THE TEMPEST”]:

PROSPERO:

But this rough magic

I here abjure, and, when I have required

Some heavenly music, which even now I do,

To work mine end upon their senses that

This airy charm is for, I'll break my staff,

Bury it certain fathoms in the earth,

And deeper than did ever plummet sound

I'll drown my book.

[END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Prospero must be Bacon’s creation, he must, even though, after much exertion, the Baconians never found the hidden cipher to confirm it. By the way, that search did have an unintended consequence.

PROF. JAMES SHAPIRO: One of the people who got invested in the ciphers early on, a brilliant man named William Friedman, became a codebreaker because of that.

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

And he was responsible, along with others, for helping to break Code Purple, the great Japanese code that was responsible for the loss of so much life in the Pacific theater during the Second World War.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So victory in the Pacific.

PROF. JAMES SHAPIRO: Thank God for the Shakespeare controversy.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: But the certainty that Bacon wrote the plays and expressed his personal pain through characters like Prospero gave way to another candidate as author, another character through which he spoke.

[CLIP]:

HAMLET: Bloody, bawdy villain!

Remorseless, treacherous, lecherous, kindless villain!

O vengeance!

Why, what an ass am I!

[END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Hamlet was not a magician or a king or a fierce and fatal warrior like Macbeth. Hamlet was a kid, a tangle of impulse, desire and doubt. Hamlet was modern. As Victor Hugo said in 1835, “Hamlet is not you or I. He is every one of us. Hamlet is not a man; he is man.” And he’s just what the doctor ordered.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

PROF. JAMES SHAPIRO: Sigmund Freud, at the tail end of the 19th century, was struggling. Freud's father died and he was thrown into a powerful depression that he struggled to find his way out of. And he came up with the theory that we all know as the Oedipal theory, that men want to kill their fathers and sleep with their mothers. But the real story he was grappling with was not the great story of Oedipus Rex, but the story of Hamlet. So Hamlet gets rewritten, not as a political story, but as a story of a man who is wrestling with the death of his father and who can’t kill Claudius because Claudius has acted out his own Oedipal desires. Claudius has killed Hamlet's father and Claudius has slept with Hamlet's mother, so you can’t kill somebody for doing what you deeply desire to do.

[CLIP]

HAMLET:

Why, what an ass am I! This is most brave,

That I, the son of a dear father murdered,

Prompted to my revenge by heaven and hell,

Must, like a whore, unpack my heart with words.

[END CLIP]

PROF. JAMES SHAPIRO: It all clicked for Freud, and he was so excited, because he had not only figured out how he thought everybody behaved in the world but he also had solved the mystery of Hamlet.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And the fundamental fact was that Hamlet was written after the death of Shakespeare's father.

PROF. JAMES SHAPIRO: Shakespeare, as far as Freud knew, and he got this from a biography by George Brandis, wrote “Hamlet” immediately upon the death of his own father, John Shakespeare, in 1601. Shakespeare’s father dies, Shakespeare works out his Oedipal complex. Freud’s father dies a couple of hundred years later, and Freud works out his Oedipal complex and solves the mystery of Hamlet in one go! What a great day that must have been.

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

He started promoting this idea and everything was going pretty well, until George Brandis wrote a follow-up book that indicated Shakespeare had written “Hamlet” before the death of his father. So if you’re Sigmund Freud, you're left with two choices, one say, my theory’s still pretty good but the basis of it is untrue. Or you could say, the only explanation has to be that William Shakespeare did not write “Hamlet.” Somebody else whose father had died who had a mother he longed for must have written it.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Enter Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, a one-time ward of Queen Elizabeth, writer, art patron, world traveler.

PROF. JAMES SHAPIRO: Yeah, I mean, de Vere was captured by pirates, and so was Hamlet. De Vere’s father died young, allowing Freud to make the argument for that Oedipal figure.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm. [AFFIRMATIVE]

PROF. JAMES SHAPIRO: De Vere wrote poetry. He was praised as a writer. And –

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Had three daughters like Lear.

PROF. JAMES SHAPIRO: There you go.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: But the biography of de Vere is really a pretty dissipated guy and who wasn't even in the country a lot of the time and –

PROF. JAMES SHAPIRO: Yeah. If you truly want to be honest about it, then you have to accept all the biographical details and read the life against it. For example, some of de Vere’s aristocratic friends claimed that de Vere had sex with an animal. Does that mean we read the end of “Richard III” “My kingdom for a horse”

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

- in a romantic way? I mean, if you’re in for a dollar you gotta be in for the whole thing. So it’s, it’s a tricky, tricky road to follow,

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Anther little bump in that road is death.

PROF. JAMES SHAPIRO: Yeah, he died in 1604, before the last decade of Shakespeare's writing career. That has never been an obstacle for believers who –

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So what plays did he write posthumously?

PROF. JAMES SHAPIRO: Well, he must have put in a drawer, in 1604 before he died, “Measure for Measure,” “King Lear,” “Macbeth,” “Antony and Cleopatra,” “Coriolanus,” “Pericles,” and “Pericles” is written with George Wilkins. It’s not just dead men don't write plays, dead men do not collaborate with living writers on plays.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: But many have believed those plays were put in a drawer, such actors as Orson Welles or John Gielgud, Jeremy Irons, Supreme Court Justices John Paul Stevens and Antonin Scalia and filmmaker Roland Emmerich, who makes Oxford’s case in the 2011 film, Anonymous.

[CLIP]:

ANNE: Why must you continue to humiliate this family?

OXFORD: The voices, I can't stop them,

They, they come to me,

When I sleep, when I wake, when I sup,

when I walk down the hall.

The sweet longings of a maiden and

surging ambitions of a courtier,

the foul designs of a murderer,

the wretched pleas of his victims.

Only when I put their words,

their voices to parchments,

Only then is my mind quieted.

[END CLIP]

PROF. JAMES SHAPIRO: I think it’s deeply disturbing to a lot of people to imagine that somebody who grew up in a middling class, who received a grammar school education, which is equivalent to a college education today, could write the greatest works ever written. Their gorges rise at that possibility. They don't want to believe it. They want to believe that you have to have money and prestige and access to do so. They don't fundamentally believe in the power of the imagination.

One of the great things about Shakespeare deniers of all stripes is there’s never a moment where they admit defeat. And I think they never get to that point because as the world changes, our notion of who Shakespeare is keeps changing.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: As Ariel said in “The Tempest” -

“Nothing of him that doth fade

But doth suffer a sea-change

Into something rich and strange.”

Up next, quite possibly history’s most inspiring and perilous performance of Shakespeare. This is On the Media.