BROOKE GLADSTONE: This is On the Media. I’m Brooke Gladstone.

Words are like matches, useful but if they’re crafted badly or handled carelessly they can spark and make you flinch. The subject of this hour is more like a Roman candle.

[KNOCKED UP CLIP]:

JONAH: You know what I think you should do? Take care of it.

JAY: Tell me you don't want him to get an 'A' word.

JONAH: Yes, I do, and I won't say it for little Baby Ears over there but it rhymes with “Shma-shmortion.” I'm just saying -- hold on, Jay, cover your ears -- You should get a shma-shmortion at the shma-shmortion clinic.

[END CLIP]

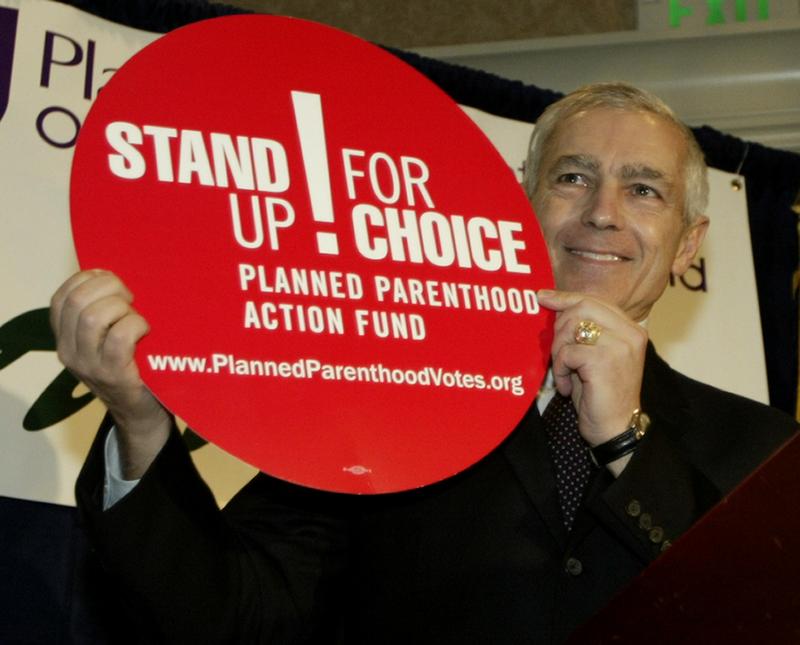

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Even the words we choose with care are fraught with danger. They are inherently political, and political phrases simplify and divide and distort. For years, supporters of abortion rights have described themselves as “pro-choice,” the political contrast to “pro-life.” Politics is so embedded in both phrases, the AP Stylebook suggests avoiding them altogether.

Dorothy Roberts is a professor of law and sociology at the University of Pennsylvania. She believes that in the abortion debate the phrase “pro-choice” is problematic because its politics miss the point.

DOROTHY ROBERTS: The problem is that in the United States not everybody has the resources to actually make a choice. If you don't have the money to pay for an abortion, what good is that right to choose? From the very beginning of the pro-choice movement, especially after the Roe v. Wade decision, there was an effort to start blocking poor women from getting abortions, with the passage of the Hyde Amendment that denies Medicaid funding for almost every abortion. And states have also denied Medicaid funding. Right to choice has come to privilege mostly white middle-class women who do have those resources.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: The idea of pro-choice, it's a liberal notion, and yet, it aligns with a, you wrote, “neoliberal market logic that relies on individuals’ purchase of commodities to manage their own health, instead of the state investing in it.”

DOROTHY ROBERTS: Choice implies that the market is fair, ignoring the social inequalities that continue to shape many people's lives. And then, when they want to terminate a pregnancy and they can't get access to an abortion provider, they can be blamed for their bad choices, that they just have the inability to make it in the market, and then even punished for those choices. And the choice framework doesn't oppose that way of thinking.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Right.

DOROTHY ROBERTS: It plays right into it.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm. [AFFIRMATIVE]

DOROTHY ROBERTS: As opposed to the question, how do we give Black and Latina girls living in poor neighborhoods more opportunities, better prospects for their futures? That's what the question should be.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Can you tick off some of those policies that work against the kind of reproductive freedom that the pro-choice movement is supposed to help ensure?

DOROTHY ROBERTS: I would argue that the pro-choice movement historically hasn't had a sustained major effort to block the Hyde Amendment. I'm, I'm not saying that pro-choice activists haven't addressed the Hyde Amendment and the lack of funding for abortion, but it hasn't had the prominence. It should be equally as important as Roe v. Wade, itself, but then there's a whole slew of policies that haven’t fit into the mainstream pro-choice movement, that are targeted primarily at women of color, to keep them from having children, that devalue their right to bear children is --

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Such as?

DOROTHY ROBERTS: Well, coercing women in prison to be sterilized. There was a revelation recently about a sterilization program in the California prison system, about 150 women who had been sterilized while incarcerated, done in violation of the ethical rules. Many would argue, including myself, that sterilizing an incarcerated woman is a form of coercion and violates human rights. Well, here we go again with maybe they made the choice, maybe they even signed a form, but under the conditions of being locked up in prison.

Welfare family caps or child exclusion policies that deny to women receiving welfare any additional benefit if they have another child while on welfare, that is a form of government policy deliberately implemented to deter women on welfare from having children.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm.

DOROTHY ROBERTS: Another is the prosecution of women for using drugs while pregnant. Now, in the 1990s, the main targets of these prosecutions were black women who smoked crack cocaine while pregnant.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Yeah, it turned out there were really no crack babies.

DOROTHY ROBERTS: That's absolutely right. It was -- it hinged very much on this false perception, in the media, primarily, but also supported by some very shoddy research, that crack cocaine caused these monstrous effects on the fetus and that these babies were going to lack social consciousness, that they were gonna have all sorts of health problems, they were going to be prone to be criminals. And all of that has proven to be false. That is an example, though, of a policy that punishes childbearing, not that punishes the decision to terminate a pregnancy. But it also shows the link between the criminalization of pregnancy and abortion rights because what it has produced is the view that the fetus is to be protected by law and that pregnant women should be punished for harming fetuses. Well, it's very hard to distinguish criminal charges against a woman for harming a fetus that she intended to carry to term and for abortion. And, in fact, in some of these cases the prosecutions are against women who try to induce an abortion, and they're being charged with killing a fetus.

So the failure, I think, of the pro-choice movement in the late 1980s, 1990s to take up the cause of pregnant women, primarily black pregnant women, and advocate for their rights has now allowed for this fetal-protection craze that is harming the right to abortion.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So let's assume we can toss out pro-choice, even though it's so enshrined now in our cultural argument, what would you prefer?

DOROTHY ROBERTS: Well, there’s a growing movement of women of color, feminist activists who are proposing that we replace “choice” with “justice” and we call this new framework “reproductive justice.” Take the focus that has been on an individual woman's right to choose and place it on the social conditions that are necessary for women to have true equality and freedom and well-being. And that requires more than protecting the legal right to choose. It requires social change.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Justice, not just rights.

DOROTHY ROBERTS: Yes, justice, creating a society where all people have the resources and the social conditions they are entitled to. Healthcare, education, housing, food, freedom from state violence, all of these are required for women to have real reproductive freedom, but it requires justice.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

And so, we would then see reproductive justice as linked to the movement for universal healthcare, to the movement for economic justice, environmental justice, Black Lives Matter. All of these movements are connected to reproductive freedom because they all are directed to creating a more just society.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Dorothy, thank you very much.

DOROTHY ROBERTS: Oh sure, my pleasure. Thank you, Brooke. I really appreciate it.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Dorothy Roberts is a professor of law and sociology at the University of Pennsylvania and author of the book, Killing the Black Body.

[MUSIC/MUSIC UP & UNDER]

That’s it for this week’s show, which was conceived (no pun intended) by WNYC reporter Mary Harris.

On the Media is produced by Alana Casanova—Burgess, Jesse Brenneman, Micah Loewinger and Leah Feder. We had more help from Isabella Kulkarni. And our show was edited by me. Our technical director is Jennifer Munson. Our engineers this week were Sam Bair and Terence Bernardo. Katya Rogers is our executive producer. Jim Schachter is WNYC’s vice president for news. On the Media is a production of WNYC Studios. Bob Garfield will be back next week. I’m Brooke Gladstone.