BROOKE GLADSTONE: This is On the Media. I’m Brooke Gladstone. Sherri Chessen, also known, to her frustration, by her married name, Finkbine, loved kids, had four little ones, including a toddler, and a day job spent with more kids on Arizona's NBC affiliate where she was known by yet another name, Miss Sherri of Romper Room. She was happily pregnant again. The year was 1962.

[CLIP]:

“MISS SHERRI”: Romper, bomper, stomper boo. Tell me, tell me, tell me, do. Magic Mirror, tell me today, have all my friends had fun at play?

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Early in her pregnancy, brought low by morning sickness, she tried a sedative her husband Bob had brought home from London. The brand name was Distoval, the generic name, she learned, was thalidomide. She also learned of the deformities wrought by the drug in Europe. She saw a photograph of five babies without arms or legs, and she felt a kicking time bomb inside of her. She feared for others who might be at risk so, always impulsive, she called her local newspaper.

SHERRI CHESSEN: I was thinking of, oh my God, there had been a contingent of Arizona Army Guardsmen over in Germany where the drug was first synthesized. Somebody could have brought it back from there. So I picked the phone, called the editor of the paper, and he wasn't there but his wife was. She said, our medical reporter is doing an article on thalidomide, may he call you? And I said, of course, but he won’t use my name, will he? She said she wouldn’t use my name, and they didn’t, although on Monday morning, page 1 of the paper, black border around it, “Baby-Deforming Drug May Cost Woman Her Child Here.” And it went on to say Scottsdale schoolteacher and they had four small children. And I thought that was narrowing it down quite a bit. We let it go at that, and I went to work in “Romper, bomper, stomper boo.”

When I got out of doing the show, somebody said, you have an important call. And it was my doctor saying, because of the story in the paper, albeit anonymous, I cannot do the operation because any person could make a citizen’s arrest. And I thought, a citizen’s arrest? This has nothing to do with anyone. This has to do with my family, my children.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Four children under the age of seven. She asked what office would be responsible for handling a citizen’s arrest and, being Sherri, she called to give them an earful. And a young attorney picked up the phone, listened to her righteous indignation and replied --

SHERRI CHESSEN: I know who you are. I have a four-year-old [LAUGHS] daughter named Valerie, and I had the flu last week and every morning from 11 am to 12 we did Romper Room with you. You’re Miss Sherri. And he said, if it comes to your needing a lawyer, I will do anything I can, pro bono, to help you. That afternoon when they decided to go into court and file a lawsuit, that brought not only the Arizona press but the whole damn world down on my shoulders.

In Arizona law at the time, an abortion is legal “if necessary to save the life of the mother.” Period. What the attorneys decided to do was to send me to a psychiatrist who would make a declaratory statement on the word “life.” Did life have to be physical life and dying on the operating table? Could life be mental illness?

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Did you resent that idea, that you had to be shown to have a mental illness of some kind before they would consider an abortion?

SHERRI CHESSEN: Brooke, I didn't resent anyone who would in any way, shape or form help me to avert this kind of a tragedy.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm.

SHERRI CHESSEN: At that time, you're grasping at straws. People were telling me to fill a bathtub with gin, and I didn’t know if they said drink it or, or sit in it. And they [LAUGHS] -- sorry, I have a weird sense of humor.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: She would come to need it.

SHERRI CHESSEN: The first psychiatrist was showing me flip cards and he said, now, you say the first thing that comes to your mind. And I thought, oh boy, Psychology 101!

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm.

SHERRI CHESSEN: He showed me this card of a woman lying in bed, a man standing beside her with his pants either half on or half off. And I gave him all sorts of flippant little answers. What he was going for was some devious, ugly reason I wanted an abortion --

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

-- that had to do with that it wasn't my husband's baby. He kept throwing these things at me that had all this sexual connotation. And I said -- uh -- [LAUGHS] you know, he was so far off. He not only recommended that I have the termination but that Child Services take my four children away because I was an unfit mother and that I, further, be sterilized. So after that, we had to go to another psychiatrist, and I walked in, and somebody very avuncular, you know, like, hi, Uncle Benny. [LAUGHS] He said, would you like a donut? And I thought, would I like a donut? I was sitting on the edge of my chair, expecting more of the same. And I said, aren’t you gonna ask me some questions? And he says, oh no, it’s already been recommended to a three-man medical board to okay this abortion, and I may as well have a donut and just wait for some time to pass because [LAUGHS] he wasn’t gonna ask me any questions.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: She says that doctors in that part of Arizona were already doing about 300 abortions a year. They just didn’t call it “abortion.” They called it “D&C” -- dilation and cuterrage.

SHERRI CHESSEN: This one was just going to be another one just like that, but somebody, namely me, opened her mouth and [LAUGHS] started a, a landslide.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Her doctor's Catholic associate found out and threatened to expose him, so he had to drop out. The doctor who delivered her last kid refused. Her uncle who ran a hospital in Denver promised aid but withdrew it when the news of the story reached there, as it eventually reached across the world. Then Japan was suggested but, fearing anti-Japanese demonstrations, the consulate denied her a visa.

[CLIP]:

REPORTER: What are your plans after Sweden?

SHERRI CHESSEN: I just want to do what’s right for myself and my family. I don’t feel bitter towards anyone. I, I don’t feel bitter towards people who oppose this religiously. I only hope that they can feel some of what’s in my heart in trying to prevent a tragedy from happening.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: A newspaper in Stockholm agreed to arrange and cover the cost of the abortion in exchange for an exclusive. There, she endured three weeks of what she called “interrogations” in the midst of a media melee. And then it was done.

SHERRI CHESSEN: And then they found out the baby had no arms. I asked, like I had asked four times before, if the baby were a boy or a girl, and the doctor said -- and I’ve never forgotten that -- it was not a baby, it was abnormal growth that never would have been a normal child. And that's the way I helped heal myself.

We left Sweden, went to Bob's hometown in Indiana for a week or so, went back to Arizona, found out I had lost my wonderful job by the NBC vice president, and I used to say “aptly named Ray Schmucker” --

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

-- but I -- he has since died. [LAUGHS] He told me I was no longer fit to handle children. And a couple of years later he had the audacity [LAUGHS] to call me, after he fired me. His daughter was pregnant and wanted to know what we knew about --

BROOKE GLADSTONE: He wanted you to help him --

SHERRI CHESSEN: He wanted me to help his daughter to find an abortion. So people are hypocrites. Look at Dick Cheney and how against gays he was, until Mary Cheney decided she was a lesbian and then, all of a sudden, you know, ‘cause people are people. We’re all the same. But everybody’s wrapped up in these trappings that make them seem holier than thou, but they're just as weak or just as loving when it comes right down to their own problems.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Do you think your story caught on because you seemed such a middle American Everywoman, so relatable, so, dare I say it, “white”?

SHERRI CHESSEN: Maybe I am to represent “Everywoman,” so to speak. I loved kids. My husband was a teacher, a high school teacher, the fact that we were an intact family, at the time, and I wasn't trying to get rid of a baby because I didn't have enough money or I wanted to finish my degree or I had enough kids. I wanted that child. If it had to happen to people that would soften the edges for a lot, well, they’re lucky it happened to us. I, I, I wanted that child.

And, and that’s another thing, that there could be medical reasons for abortion and they get it mixed up with the moral stuff, with the legal stuff.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Do you believe that women should be able to decide whether or not to have a pregnancy for any reason, or do you think it should be limited to medical things?

SHERRI CHESSEN: I would never question anybody's legal, medical, whatever reason, because that’s a private matter. And while I will work my fanny off to get you the right to do whatever you deem is right for your family, you do not have to tell me the reason. You do not have to tell me why. You do not have to justify it.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: You’re 85 now. You’ve seen the complete modern history of abortion politics unspool in this country. Has it shifted or is it the same debate?

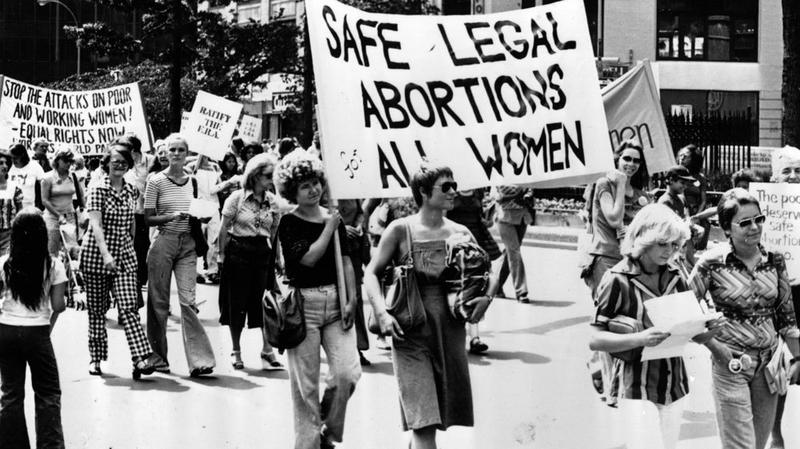

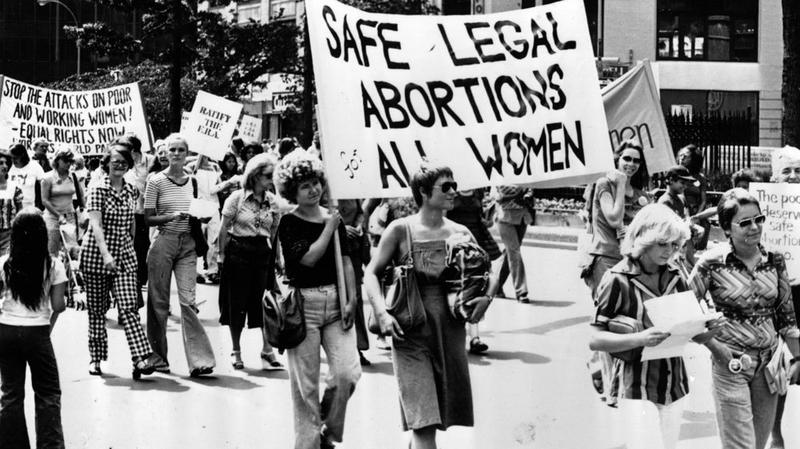

SHERRI CHESSEN: In 55 years, it hasn't shifted an inch, in my opinion, and it makes me feel like, oh my God, not this again. I’m saying things to you today at 85 that I said at 30, and I -- we get n -- I shouldn’t say we get nowhere. We got Roe v. Wade. Now we have to fight to protect it. It’s, it’s just going to, you know, go round and round. In fact, I’ve got a little thing in front me. It says, “The wheels on the bus go round and round.” And that’s -- the wheels of abortion go round and round and round and round.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Sherri, thank you very, very, very much.

SHERRI CHESSEN: Well, you’re welcome, honey. Just know that you will be helping someone who hears it, because that’s always what happens.

[“THE WHEELS ON THE BUS” CLIP]:

Beep-beep [MUSIC] beep-beep!

The mommies on the bus go, shh, shh, shh

Shh, shh, shh, shh, shh, shh.

The daddies on the bus go, shh, shh, shh

Shh, shh, shh.

[CHIMES/END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Sherri Chessen, formerly of Romper Room, now a founder of Gorp, a group that offers children’s books and teachers’ guides on such issues as bullying, sexual abuse and gun safety. She's lived through the era of not talking about abortion at all, into the era of talking about it incessantly.