Monrovia's Marketplace of Ideas

BROOKE: This is On the Media, I’m Brooke Gladstone reporting from Liberia under the wing of Rodney Sieh, editor of FrontPage Africa. Today, Rodney, Mae, Meara and I drop in on a live radio show hosted by the magnanimous Mary Williams.

SIEH: We have a guest in town for the next seven days from On the Media program. It's a media analytical program that comes out of NPR radio. Once a week. It's Brooke Gladstone, she's the host. This is her producer, Meara Sharma.

WILLIAMS: Welcome to our studios!

BROOKE: Thank you so much for letting us invade. The reason why we're here is simply to report the story from a Liberian perspective.

WILLIAMS: Are you aware that we have another issue actually. The Supreme Court says there's a stay on the elections. So we're like: 'Oh! Ok, really? Why is there a stay on the elections?' I've never seen anything like this before. We had an Ebola situation, election was supposed to be held on the 14th of October, which is what the constitution says. Now we had Ebola, so common sense would tell you that you can't hold the election. But, other people said, well there's going to be a constitutional crisis if the election is not held this year. How long are you in town for?

BROOKE: We're here for a week.

WILLIAMS: How are you dealing with the accent? Are you understanding the accent?

BROOKE: We were having a discussion about that. The accent is very tricky. One expression is...

AZANGO: White woman coming.

BROOKE: Say that again Mae.

AZANGO: White woman coming.

BROOKE: White woman coming.

[laughter by all]

BROOKE: So now I know, when I hear that. Usually with applause.

WILLIAMS: If you have a question -- please ask it. 0247 2211 11 you can call that number now. 0247 2211 11

(WILLIAMS TALKING ON THE PHONE TO GUEST ON HER RADIO SHOW)

WILLIAMS: Hello.

MAN'S VOICE: Hello.

WILLIAMS....Yes

MAN'S VOICE: I want to say hi to the white woman. I listen to her - I find it difficult to understand her.

WILLIAMS: Rodney's her interpreter. Rodney will interpret.

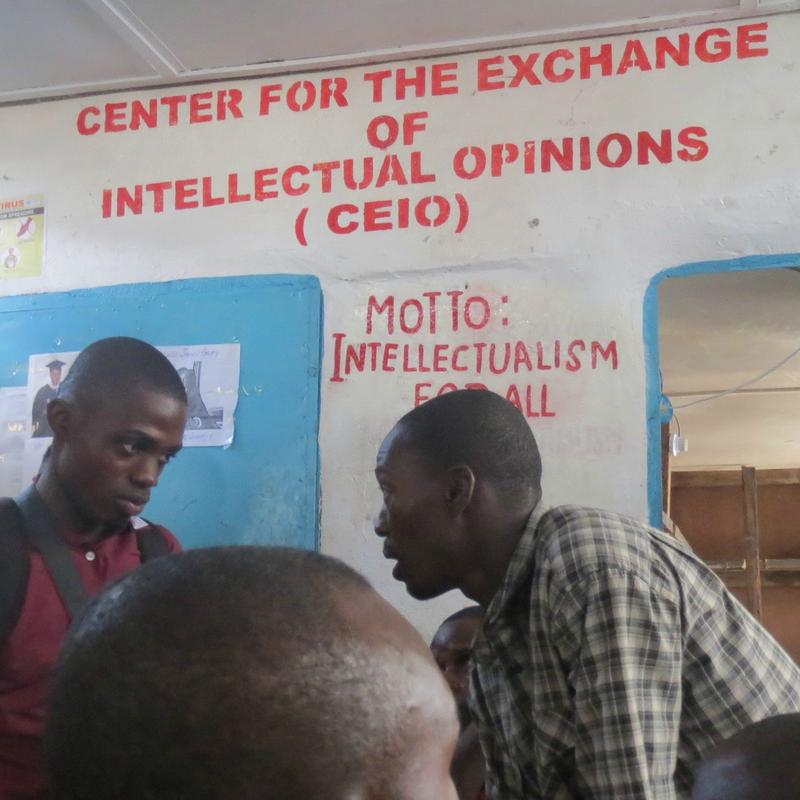

BROOKE: You heard Mary refer to a stay on the senate election already twice delayed, now scheduled for December 16th. If it doesn't happen, half the 30-member Senate will be unseeded, leaving 15. And 16 are needed for the final passage of the law. They could convene an interim government, but given Liberia's history of instability and civil war few openly favor that. Then again no one wants to get sick, either. Such issues are argued in tea house debating clubs called hatai, filled to the rafters with fiery young men with lots of time on their hands. We visit one such club, the "Center for the Exchange of Intellectual Opinions" which is a cement room on a crowded street with a zinc roof. The topic is the supreme court's pending decision on whether to delay the election. On this day - Stephen Kollie of FrontPage Africa is running the show.

KOLLIE: So what is your name?

BARCLAY: This is Joseph Jeremiah Testimony Barclay.

KOLLIE: What is your opinion on the elections?

BARCLAY: The international community will refer to us as stupid people who do not care for the life of our people. Laws are made to protect the healthiness of our society. So if our people are not being protected under our laws, those laws can still be revisited. You can not have this reckless virus that our people are succumbing to day by day, even on their sickbed, and you're going to elections. It's laughable, its draconian, its ill-fated and it's backward.

KOLLIE: Thank you very much. Sir what is your name?

KASAWISA: Franklin Kasawisa, executive chairman for the Center for the Exchange of Intellectual Opinions.

KOLLIE: Do you think elections should go ahead or elections should be postponed.

KASAWISA: Election must be held. If you look at those cleverly agitating for the cancellation of elections. These are people who are calling for the resignation of the President. They are on record. People are yearning for an opportunity to refactor themselves back into the matrix of power. They feel that establishment of an interim leadership will bring them back into the fray.

KOLLIE: These guys are preaching for the safety of the country. Do you think Liberia is safe right now to have people clustered together having relations and so forth.

FRANKLIN: The argument is very lazy. A very lazy argument that rests on a slippery hill. Why are you not calling for the closure of the marketplaces and all entertainment centers. Because the probable and confirmed cases of Ebola had dropped considerably. Any attempt to not hold election before January 16th, the President of the nation will be addressing a makeshift legislature. This country is bleeding! The good people of Liberia will prevail over the handful of narrow-minded and evil-minded individuals. Thank you very much.

SOUND: CROWD

BROOKE: The next day the Center was hosting the Minister of Information.

KOLLIE: Members of CEIO, sympathizers, well wishers. We are privileged to have in our midst today, for the first time, the honorable Minister of Information for Cultural Affairs and Tourism. The tough-talking, very eloquent, and sophisticated intellectual. Honorable Minister, this is the Center for the Exchange of Intellectual Opinions. This is that platform that commands critical minds on a daily basis who assemble here to cross-pollinate ideas of critical national concerns. If for any reason your can boast that your government is plying the route of the right trajectory it's as a result of the views you sample from the ambiance of the intellectual centers across the length and breadth of the republic. We are happy to have you here minister, but I crave your indulgence to please take this glass of hatai. This substance is what we take here that stimulates our intellectual nerves.

MINISTER: Good afternoon to all of you. People have asked me all sorts of questions. Mr. Brown you were once the President's harshest critic. I am convinced the President has asked me to serve in this government, not to shut me up, because to shut me up is a very difficult thing.

LAUGHTER

MINISTER: She said "notwithstanding your serious foundational, principled disagreement I believe we can find a common ground at which your talent and mine can be used in the best interest of our people" and I said '"YES." No regret, one day for my decision.I will disagree with you on your politics and on my principles, but as to whether we can work together to lift up ordinary Liberians like you there will be no disagreement. I know where I have come from.

BROOKE: He talked for over an hour,but never genuinely engaged in the promised intellectual exchange of opinions. He wasn’t big on that. Yet he insisted his President was. It’s clearly Rodney’s view that officials should not be given a choice in the matter. When he launched Frontpage Africa, while working for a newspaper in Parsippany, New Jersey he filled it with voices from across the Liberian diaspora.

SIEH: I started FrontPage Africa with one laptop. It was a Dell computer. And I sat in my apartment in New Jersey. I had one correspondent in Liberia. Then two. Then three. I used my paycheck in America to pay them. Critics said, "Oh, you in American writing about the government. You're not in Liberia." It got to me and I said, you know, I'm going to go back home. I knew that it would be difficult because the stories that we did on the internet have stepped on a lot of people's toes. When we got home, we had two arson attempts on our building, to try to burn us down. People sabotaging our equipment. Later on we started getting arrests. The first time was a commentary about a 13-year-old girl who was raped. The writer said the Supreme Court was biased in the case. And I was called to explain why I published the commentary. They asking me questions about what school did you go to. What qualifies you as a journalist. Badgering me like a criminal. And I told them I said, "With all due respect, the opinion pages is like a marketplace of ideas and you're behaving like dictators." And last year we of course we got the 5,000-year sentence. I spent 50 days in the prison, eight prisoners in the room. Very small. And the toilet was also the shower. A big hole. And they had like a footstool on top of it. For you to shower. And when you're sleeping, the hole is still open. So you all inhaling that thing from the hole. And I think that's why I got sick. You don't want to be a human being in that place. That place is for dogs.

BROOKE: Tell me about your parents.

SIEH: So my mother had epilepsy. My father was an engineer. He was the first Liberian engineer to get a scholarship to America. He was a very smart guy but he had a weakness in drinking. So he wasn't really there for us. He would take me to the bar sometimes to watch him drink, and leave me there. And then his friends would pick him up and take me home the next day. I was raised by my aunt and my uncle and they taught me a lot about discipline and going for what you want in life and getting it.

BROOKE: Journalism? Why would that even occur to you.

SIEH: My great granduncle Albert Port, he published a pamphlet that had a lot of information about corruption, about nepotism.

BROOKE: Did it come out once a week?

SIEH: It came out when he felt like writing it. So he was jailed for writing about corruption.

BROOKE: Did you know your uncle?

SIEH: I was in high school when he died. Saturdays he would prepare the church for Sunday service and he was in the church bell hall one time and when he rang the bell the bees came and just swarmed him, and that's how he died. The funeral was massive, people came from all over the place. He was not a very wealthy man. He had nothing much. But he changed the way people see things in Liberia.

BROOKE: So did he ever say to you, "Rodney, follow in my footsteps."

SIEH: I think it came naturally. In high school, I worked on the newspaper. And then the war came, I work for the BBC. And during the military take over of 1994, and they kick me out. I went to London spent some time there. I went to the States, I got asylum. Went to Hunter College. They sent me to Kansas City Star as an intern. Newark Star Ledger, and then the Syracuse Post Standard and then gradually they hired me at my first job.

BROOKE: And then they horrible snows fell.

SIEH: Horrible snows fell. I moved to Virginia. The Virginia Daily News. And came to Jersey on the east coast with the Parsippany Daily Record. And it was there I stayed until I decided that the print media was kinda getting challenging in America.

BROOKE: Ya think?

SIEH: So I started FrontPage Africa.

BROOKE: This is going to be a weird question. One thing that Meara and I noticed is that you seemed really jazzed and really sad.

SIEH: Besides my uncle Albert Port my next person I admire was my uncle Kenneth Best. In him I saw someone who I could emulate, I could model my life after. When Samuel Doe closed down his paper, The Observer, in the '80's I went to his house, his wife made bread to sell that helped the family stay afloat and I sold the bread. When the paper was operating, after school, I took the papers in the streets, 'Buy your Observer, Buy your Observer' and I wanted to be him. He was in the States. He came to me to help him start The Observer again. So I started the online Observer. But, there were a lot of stories we ran that he didn't like. So we butt heads a lot of times. His friend, who was the ambassador to the US at the time.

BROOKE: Which embassy?

SIEH: The Liberian Embassy in Washington. The audit report was done on the embassy funding. They funneled money through the embassy to the States. And we did a story about it. And he didn't like it. He told me to retract the story. I said I can't do it. And that's how we fell apart. And I started FrontPage Africa.

BROOKE: Does he talk to you anymore?

SIEH: We don't speak. If I see him I will pass only because I've tried speaking to him he won't speak to me, so I stopped trying. All I ever wanted to do in life was to emulate what he was doing. And I can't for the life of God figure out why he hates me so much. I hope that one day before I die or he dies, we can make peace. But I don't see it, because the friction has gone beyond a point of being repaired.

MEARA: Can I ask whether you want to have a family?

SIEH: I've tried. I've had relationships that could have been more serious but because I was trying to start FrontPage Africa I had a lot of, um, people who didn't patience, who left me.

BROOKE: Course you never let your staff off, so you have them around.

SIEH: Yeah, we spend a lot of time together. I think they like what they do. When I came from prison they had a big ceremony in the streets, there was a big parade and stuff, and I broke down crying and people didn't understand why I was crying. It's like, those people stood by me. They were offered jobs, they could have gone anywhere and left me when I was in the lowest moment but they stayed behind because they know that deep down I cursed them at times, I slammed the doors and crashed the doors but I know that I tried to make them the best that they can be. And that's why I think they stayed.

BROOKE: You love them.

SIEH: Yeah.

BROOKE: Let me just stipulate, for the purposes of a hypothetical, that you're not getting along with your uncle now because you confronted him with his limitation. His friends, his alliances, his alliances with President Sirleaf; these were things he decided he didn't want to compromise with uncompromising journalism. Can you see at some point when you're older, maybe when you're as old as your uncle is, the prospect of prison or the promise of an easier life, that you might find yourself in his position sometime.

SIEH: I hope not. I won't lie to you, I can never say never. The reasons I don't have too many friends here is that people who think they are my friends, they figure that because you're a friend of theirs, you have to protect them. And this country is very fragile. It's very small. Everybody knows somebody. I get calls every day from people who say, "How could you do that to your friend" and what can I tell them? We're just doing a job.

BROOKE: Sounds lonely.

SIEH: It is. It is. That's why people, they don't see me out and they say, "I think he's gay. We haven't seen him with a woman before so he must be gay" I take it in stride because that's the work I chose to do. During the war I was a refuge. My epilepsy mother was in a wheelbarrow I took her from place to place. I've seen dead bodies floating on the rivers. I've seen my friends get shot. I came close to be killed several times during the war. You wanna celebrate the fact that you came back home to help start a vibrant paper in a vibrant democracy. I don't do it because I hate the government. I'm not anti-government. I am pro-Liberia. Transparency, accountability those are the things that the lack of them took us to years of civil war. If we don't tell the people what's happening here, they will continue doing what they're doing. Gonna be like a recurring dream we're having. They will hate you for what you write. But we need to tell these stories in a way that, I think, only we can.

BROOKE: When Rodney was arrested that second time, thousands of people filled the courtyard and the street, to obstruct the police taking him to Monrovia’s South Beach Prison. This came up during a car ride.

RADIO SOUND

SIEH: Hey Brooke, this my song.

BROOKE: A favorite song? No, a song in which he’s named, in conjunction with freedom of speech. Turns out Rodney’s kind of a folk hero.

MUSIC

You say freedom of speech, Rodney Sieh...

BROOKE: What was that?

MEARA: Rodney Sieh! He's in the song.

AZANGO: When they say freedom of speech, when Rodney Sieh talk you carry him to South Beach.

MUSIC

BROOKE: It says something about Liberia, that, even with it’s dismal economics, politics and disease, there is engagement, commitment, the power to at the very least shame people who abuse the public trust, and the courage to do it. People ask a lot was if I afraid of getting sick. I wasn’t, not once. I was careful, and hanging around careful people living meaningful lives. Ebola has publicly exposed Liberia’s vulnerabilities, and the higher the stakes, the more journalism matters. Even before Ebola, Rodney was making a difference here. Ebola generously brought us to him. But it wouldn’t let us shake his hand.

CREDITS

That’s it for this week’s show. On The Media is produced by Sarah Abdurrahman, Chris Neary, Laura Mayer, Kimmie Regler, Andrew Chugg and Ethan Chiel but this week, mostly by the inestimable Meara Sharma. We had more help from Kasia Myhailovic. And our show was edited by me. Our technical director is Jennifer Munson. Our engineers this week were Merritt Jacob, Andrew Dunn and Greg Rippin.

Katya Rogers is our executive producer. Jim Schachter is WNYC’s Vice President for news. Bassist/composer Ben Allison wrote our theme. On the Media is produced by WNYC and distributed by NPR and this week we offer a special thanks to the Ford Foundation. Bob Garfield will be back next week, I’m Brooke Gladstone.