Brooke: This is On the Media. I'm Brooke Gladstone.

Bob: And I’m Bob Garfield with a story about how reading the paper can actually bring us closer to the truth. By combing through contemporaneous newspapers, as well as official records, the Equal Justice Initiative added 700 victims to the list of more than 3,200 African-Americans already known to have been lynched between 1877 and 1950. And that’s just in the twelve southern states studied, from Texas to Virginia. The Initiative wants to commemorate the now-corrected record by placing markers at some of the lynching sites. But most important, says law professor Bryan Stevenson and director of the Equal Justice Initiative, it seeks to reclassify the great northward migration of African Americans as an exodus of refuge from terrorism.

Stevenson: There was an awareness that if you were white and you were offended by some person of color - not just victimized with a crime but offended - you had the latitude to respond to that in any way you wanted. And if that included lethal violence, torturous violence, and lynching, you were going to be protected. And in my view that made all lynchings of African-Americans during this era systematic.

Bob: You assert that even if a mob does form spontaneously, the prevailing sentiment of permission took any sense of spontaneity out of the event - it just became part of an overall social pathology.

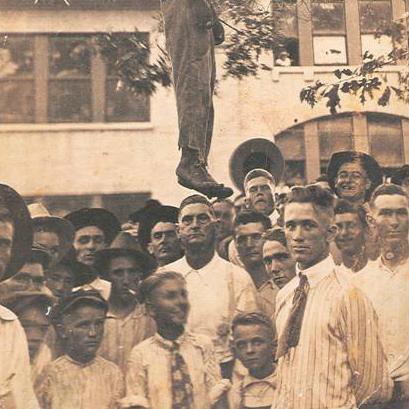

Stevenson: You'd see in some of the imagery from these events people posing next to the victims dangling body because there was no sense of shame, there was no sense of legal liability following these things. The true evil of slavery in my opinions was not involuntary servitude. The true evil of slavery was this narrative of racial difference - this ideology of white supremacy. This notion that these black people are not fully human. And the difficulty we have in this country is that our 13th amendment, which prohibited involuntary servitude, didn't deal with the narrative. And in that respect, I don't believe slavery ended at the end of the civil war, it just evolved.

Bob: Every white person was fully deputized in the shadow system of justice.

Stevenson: That's exactly right. And once the federal troops left at the end of Reconstruction, people were encouraged to use violence to enforce compliance. Some of the lynchings that we highlight in our report reveal this. There was a man named Jesse Thornton who was lynched in Laverne, Alabama in 1940, for referring to a white police officer by his name without the title of Mr. And he was grabbed, and he was killed. 1919 a white mob in Blakely, Georgia lynched William Little who was a returning soldier from WWI, an African American man, and they were antagonized by him wearing his army uniform. So he refused to take his uniform off and he was lynched. A man named Jeff Brown in 1916 was running through Cedarbluff, Mississippi to catch a train - he bumped into a white girl, and he was lynched. The idea that he had some place important to be that might cause him to even casually bump into this white woman was an offense of this order. And so he was lynched. That kind of violence, that kind of oppression, was being enforced only because there was this system that did deputize every white person to engage in this kind of subordination.

Bob: I'm puzzled as to how contemporaneous newspaper accounts of lynchings and other violence against southern blacks provided a whole lot of information for you. It would suggest that there was some degree of sympathy, or fact-finding, in the reporting, which at the time would be a shock to me - that southern papers were evenhanded in their coverage of these vigilante crimes.

Stevenson: Oh, they clearly were not. When you look at the coverage, it/s often quite celebratory, and so we were able to understand the ugliness of it, because they didn't see it as ugly, and they were therefore comfortable detailing it. How many times the person was shot, how much mutilation took place, how the person was carved up, whether there was collateral violence directed at other black homes and black churches and black community members. All of that would sometimes be detailed both because it served to reinforce the narrative and to expand the terror. But its also true that the source of a lot of our information was actually a very strong and robust black media. A black press. There were dozens of black newspapers that formed all over the country that became quite attentive to these acts of violence. They were trying to document them to show the federal government that there was a need to return the federal troops, there was a need for federal intervention and protection. It's really in reviewing those sources that had not been exhaustively reviewed before that we found a lot of the really rich detail surrounding these lynchings.

Bob: You assert that we have historically misunderstood the great migration northward by African-Americans who we have long assumed to have been seeking opportunity in the large industrial cities of the North when they moved in the years mainly surrounding WWII. And you say that the evidence that you have gathered suggest that they were not seeking opportunity but fleeing terror.

Stevenson: Throughout the 20th century the experience of African-Americans in the south was very different than the experience of others. These weren't people heading to the West in response to the Dust Bowl or the Depression. These were people, many of whom fled between 1900 and 1925 as this violence began to peak. And we did lots of interviews with people who were telling us about what they called 'near-executions,' where they would send their son, or their daughter, or their husband, or their parent to the North because they'd had an encounter with some white person in town and they weren't sure if the mob might not show up that night. Looking at the evidence around some of these lynchings was a shock to me to find out how often the last words of a lynching victim would be, "Tell my people to flee." And in interviewing the children and grandchildren of some of these lynching victims there was no question that they fled as refugees. And even when you look at these cities that are now strongly influenced by a large black population - Cleveland, Chicago, Detroit, Los Angeles, Oakland - you look at the history of people of color in those communities; they weren't actually given great jobs when they came and in many ways they continue to remain marginalized. They achieved some measure of security from the kind of overt terrorism that lynching represented but they were still subordinate. And that's why I think that you cannot understand this migration without understanding the terrorism that inspired it.

Bob: You wear another hat, and that is to provide defenses and appeals for those on death row, perhaps unjustly convicted or inappropriately sentenced to death. I assume that you see a far more than casual association between today's criminal justice system and the legacy of lynchings in the South. Or am I overstating the case.

Stevenson: No, I think there absolutely is a continuing problem in America that is rooted in our failure to deal more honestly with this history in the past. There's been a lot of protests recently in response to police shootings of unarmed black men, and these protests are responses to not just a single incident in Ferguson or Staten island, it's in response to lives being lived where people feel targeted and menaced by the police. I work in a criminal justice system where I've seen that presumption of guilt send many innocent people to jails or prisons for crimes they didn't commit. I've even been in a courtroom as an attorney and been the target of some of this. I was in a courtroom in the Midwest not that long ago sitting at the defense council's table with my suit on, and the judge walked out and he saw me sitting there by myself and he said, "Hey, hey hey, hey, you get outta here. I don't want any defendant sitting in my courtroom by themselves. You go back out there in the hallway, and wait until your lawyer gets here." And I had to stand up and say, "Oh I'm sorry your honor, I didn't introduce myself." And the judge started laughing, and the prosecutor started laughing, and I made myself laugh, because I didn't want to disadvantage my client. But afterward I was thinking about that - what is it about this judge, when he sees a middle aged black man in a suit and a tie, sitting at defense council's table, it doesn't occur to him that's the lawyer? When I think about that judge dealing with young defendants of color, do I think that those presumptions are going to disadvantage those young defendants? I absolutely do.

Bob: You are not a historian, you're a law professor, and yet here you are, presuming to rewrite the history of the 20th century. I wonder if you've gotten any push-back from historians and others in academia to your presumption to kind of tread on their turf.

Stevenson: We have a different vantage point. We're investigating racial history. We're investigating the story of how these communities were affected by these narratives of racial difference. And if anything, we've gotten a lot of encouragement from historians who I think would admit that they have too frequently focused on discourse among academicians. The reason why I want to put up markers and monuments is because I want people in the spaces to talk more truthfully about what that history represents. You go to Germany now and you are forced to confront the legacy of the Holocaust because that society has made a determination that it can't ignore that ugly reality. They can't be silent about it. They've got to talk about it. We do the opposite in america. And I don't think we can leave it just to historians to change that.

Bob: Bryan, thank you.

Stevenson: You're very welcome.

Bob: Bryan Stevenson is executive director of the Equal Justice Initiative and a professor of clinical law at NYU.