BOB GARFIELD: Self-immolation may indeed be concentrated in the East but David Buckel’s fiery death this week in Brooklyn was by no means unprecedented here. Just a few years ago, a man who had similarly devoted himself to social justice also took his life. He barely made the news.

In 2014, in the small East Texas town of Grand Saline, population 3100, a retired pastor named Charles Moore doused himself in gasoline in the parking lot of a Dollar General store and flicked a lighter. He left behind a note saying that his death was a protest of Grand Saline’s racist history and present. He wrote, quote, “I've come to believe that only my self-immolation will get the attention of anybody and perhaps inspire some to higher service.” Michael Hall wrote about Charles Moore for Texas Monthly magazine. Mike, welcome to OTM. MICHAEL HALL: Thanks, Bob.

BOB GARFIELD: Who was Charles Moore?

MICHAEL HALL: Charles was an enlightened progressive minister long before that was a hip thing to be. In super conservative East Texas, even back in 1954, he was preaching, for example, that Brown v. Board of Education was a good thing, which is just nuts in East Texas in 1954, and he caught a lot of flak for it. And he spent a lot of time fighting for people who were disenfranchised, fighting for poor people. He was personally welcoming gays to his church here in South Austin. He went on a hunger strike to try to make this a real issue for the Methodist Church and ultimately the Methodist Church made a few begrudging changes but nothing really big, although eventually, I mean, the Methodist Church, like all churches, has slowly been breaking down some of these walls. And Charles’ peers believe that he had a lot to do with that.

BOB GARFIELD: In any event, by the time he poured gasoline on himself and set himself aflame in that empty parking lot, he was a deeply disappointed man. And his suicide note specified why he was making the ultimate sacrifice.

MICHAEL HALL: He actually titled it, “Grand Saline, Repent of Your Racism.” He spoke of all the, the people who had been lynched there and, and set on fire. And he said that his sacrifice, he was going to join them in their martyrdom and to give his body to be burned.

BOB GARFIELD: Here is some tape from a documentary called Man on Fire, a, a film that sprang from your Texas Monthly piece.

[CLIPS]:

WOMAN: The majority of like the black people in this town, they are not gonna go to Grand Saline. They’re not gonna go to Grand Saline, they’re not gonna hang out in Grand Saline. They don’t have any friends from Grand Saline. And they’re just like, they’re still racist, the Klan’s there, you know, they lynch people there, they don’t like you, they’re gonna chase you out of town. They’re gonna try to fight you. I mean, like literally, like it’s like taboo.

WOMAN: I remember one, one time that we had a track meet and the next day a guy says, did you all see all those monkeys walkin’ around on their hind legs last night? And then things like that, you do hear every day. I probably heard the “n-word” every day at school.

[END CLIP]

BOB GARFIELD: However, Moore’s accusations that Grand Saline had a history of lynchings and burnings doesn't comport with actual history, does it?

MICHAEL HALL: Right. I mean, you will see no black people in Grand Saline in 2018. It has this reputation as being this terrible, terrible place for black folks. And Charles grew up there, and so, he heard these stories, and there were stories about there’s a part of town called Poletown and it was said to be a place where African Americans were decapitated and their heads were put on poles. There's a bridge there where legend had it that of many African Americans were lynched from. And so, I mean, he grew up in this cauldron of stories.

But, on reflection, and I went and talked to a bunch of people who would know, African Americans as well as some of the, the local historians in Grand Saline, and there is no record of any lynchings of blacks there. That idea the Grand Saline was this, you know, terrible lynching ground is just, just not true.

BOB GARFIELD: All right, well let's just say that the historical facts obscure the larger truth of institutional racism in this little town. But, in any event, Moore’s self- immolation, if it was meant to make a big statement, it didn't seem to do that. It didn't get mentioned in the national news when it happened and it wasn't even a big story in East Texas.

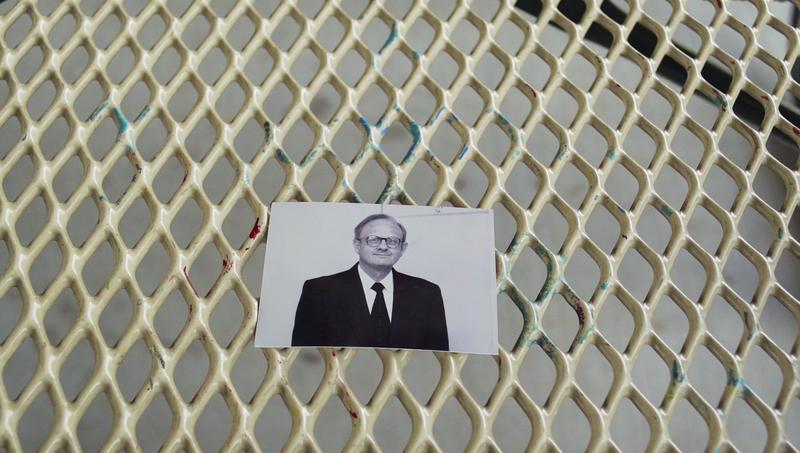

MICHAEL HALL: Right. The Grand Saline paper did a story on it a couple of days later; it didn't even mention him. When the Tyler paper did it a few days after that, they mentioned him and I think the headline was “Martyr or Madman.” It took a while for people to actually really look into why he might have done it. And one of Charles's role models was Quảng Đức, the South Vietnamese monk who had self-immolated back in 1963. Charles had his picture, the famous photograph, Charles had that picture on his desk. He had left it there to be seen, so Quảng Đức was his hero.

Quảng Đức, though, had gone out of his way to publicize what he did. They had notified a bunch of the media. Charles didn't. Instead, Charles chose this virtually empty parking lot of a Dollar General store in Grand Saline, where there were four young people taking a cigarette break from working at the spa there as his only witnesses.

[CLIP]:

OPERATOR: 911?

ANGIE: This is Angie at the Dollar General.

OPERATOR: In what city?

ANGIE: At Grand Saline, and a man is on fire out in the parking lot.

OPERATOR: The man is on fire?

WOMAN: Yes, a man just set himself on fire.

[END CLIP]

BOB GARFIELD: He had previously planned to kill himself for somewhat different reasons. Just on the question of messaging, it's hard to know what really he was trying to say.

MICHAEL HALL: Yeah, it, it really is. In his initial letters, he was protesting the death penalty, he was protesting the denial of rights to homosexuals and, ultimately, he settled on the racism, American racism, which is something that he had seen his whole life. I mean, one of his friends said, at the end, his action was a symbol of solidarity with people on the margins; it was meant to call us to respond basically for all injustice. I mean, yeah, Charles couldn't pick a single one but he was always out there for all kinds of injustices.

BOB GARFIELD: Long before his suicide, the guy made other great sacrifices, including his own closest relationships, his family. He put his pastoral work and his humanitarianism ahead of his family and ended up twice divorced, became estranged from his children. In your piece, I see a man swinging between long bouts of depression and a sort of messianic mania. I mean, if you wish to make the ultimate protest, how is the outside world to know where your protest begins and mere personal misery or mental struggle ends?

MICHAEL HALL: Yeah, I mean, that's a really good question. I mean, how can we possibly know? He left his two sons behind then and he took his wife to India, and his sons were basically raised in foster homes. Helping poor people, it was so important that he would leave his children behind. You know, I think that there is a certain amount of craziness that comes with the territory of being somebody who feels and thinks so much that he loses himself in, in his work,

He was so desperately searching for some kind of meaning, but [LAUGHS] when I went back and looked through his life, I found this unbelievable life's work. You know, he probably forgot all the individual people along the way who he helped or who he preached to or he ministered to. I talked to those people. I read the sermons he gave, which were fantastic. He was a great preacher. You could say that he lost his way; he stopped ministering and he, he stopped reaching out and just basically started reaching in.

BOB GARFIELD: Did, did he, in any way, get Grand Saline to repent or at least give some thought as to the values and history of the community? Is anyone more enlightened as a consequence of his self-immolation?

MICHAEL HALL: Whether Charles advanced the ball in Grand Saline, I don't know. I mean, we’re talking about it now -- granted, we’re only talking about it because another man did the same thing this past week. I do know that people read magazine stories and people watch documentary films and people listen to radio shows, so maybe his message is getting spread out into the world, maybe not in the way Quảng Đức did but, you know, people are talking about his ultimate sacrifice.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

BOB GARFIELD: Mike, thank you very much.

MICHAEL HALL: Thank you, Bob. I really appreciate it.

BOB GARFIELD: Michael Hall wrote about Charles Moore for Texas Monthly magazine. The piece called “Man on Fire” is also the title of a new documentary about Grand Saline, after Charles Moore’s death.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: This is On the Media.