Le Guin's Legacy

( Micah Loewinger / WNYC )

BOB GARFIELD: This is On the Media. I’m Bob Garfield.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And I’m Brooke Gladstone. Ursula Le Guin died Monday at the age of 88. According to her biographer, Julie Phillips, she had a glorious childhood, a painful and perilous adolescence and young adulthood and then finally a balanced life of family and artistic creation that enriched all who partook of it. Le Guin wrote groundbreaking, mind-bending science fiction that cut to the heart of gender, politics, morality and what it means to live and die, all in exquisite prose.

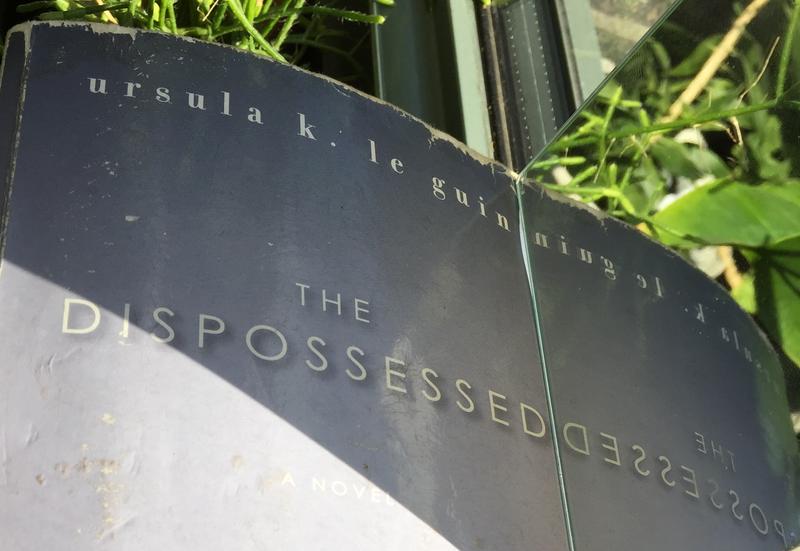

David Mitchell, author of Cloud Atlas, called her a crafter of fierce focused fertile dreams. I’d also add an explorer of radical ideas. In fact, Le Guin, a Taoist with an anarchist bent, wrote in her acclaimed political dream, The Dispossessed, that the idea is like grass. It craves light, likes crowds, thrives on crossbreeding, grows stronger from being stepped on. She believed that the most fertile ground for ideas was science fiction and defended it against literary snobs. She wrote, to think that realistic fiction is by definition superior to imaginative fiction is to think imitation is superior to invention. But she took no prisoners from any quarter, including her own. Here she is at a science fiction conclave in 1975.

[CLIP]:

URSULA K. LE GUIN: Here we’ve got science fiction, the most flexible, adaptable broad range, imaginative, crazy form that prose fiction has ever attained and we’re going to let it be used for making toy plastic ray guns that break when you play with them and prepackaged, precooked, predigested, indigestible flavorless TV dinners and big inflated rubber balloons containing nothing but hot air? Well, I say the hell with that.

[END CLIP]

JULIE PHILLIPS: She had strong opinions and she cared so deeply about science fiction, even though it wasn't the genre that she originally wanted to work in.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Julie Phillips as a writer and book reviewer who’s long been at work on Le Guin’s authorized biography.

JULIE PHILLIPS: She started out wanting to be a poet, actually, and write mainstream fiction. You know, she was born in 1929. She graduated from college in 1951. She experienced all of the ‘40s and all of the ‘50s, such a repressive time politically and culturally and socially. Hemingway was the writer to be emulated and Norman Mailer and Saul Bellow, and she just wasn't like that. And she found that realism was a small and stony ground for her work, is what she said. She needed more room.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: You wrote, it wouldn’t surprise me if future literary critics read Le Guin as an important ancestor, the writer who brought imagination into realist American literature, that writers who venture into what Michael Chabon calls the “borderlands,” literary fiction that draws on the fantastic, are almost always following Le Guin's map. You said to just think of her as the éminence grise of the American imagination?

JULIE PHILLIPS: Yeah, she came into this kind of minor genre and took a step away from the mainstream to do what she needed to do, and she ended up transforming the mainstream to be more like her. A lot of writers say that her importance to them has to do not so much with exactly what she was doing, which was pretty inimitable, but with inviting them to go their own way. She showed them that if you feel that you’re different you don't have to change yourself, you can imagine worlds in which your difference would make sense.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: That’s the thing about the genre and its greatest practitioners. They were world builders, system constructors, different systems --

JULIE PHILLIPS: Mm-hmm. [AFFIRMATIVE]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: -- than we’re used to. This was probably due to the fact that her father was a noted anthropologist and her mother wrote about anthropology. They were used to looking at the world from a long lens because they were examining worlds that were not their own.

JULIE PHILLIPS: Many of her characters in her early work are looking at other planets from an anthropological perspective, and one of the things that she says about her childhood is, I knew perhaps more clearly than many kids that there were different ways to do almost everything, so I had the sense of freedom that you can get by saying, it does not have to be this way.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Let’s talk about 1968. She's living in Portland, Oregon. She’s living with her husband, the love of her life. She releases A Wizard of Earthsea, which is the first installment in her blockbuster young adult series. She was invited to write a young adult novel by a publisher, gave it some thought and then this is what she came up.

[CLIP]:

URSULA K. LE GUIN: All the wizards in all the books that I had read in 1967 were old. They were old men, old white men with white beards and white hair and peaky caps, you know? But you can’t be an old man without having been young, and it occurred to me, well, how does a wizard start out? And, well, obviously, he’s got a lot to learn, so where do you learn things? You learn ‘em in school. So you go to a wizard school? Woo! Okay, now I’m telling you, this is 1967. [LAUGHS] There have been other wizard schools, you know.

[AUDIENCE LAUGHTER][END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: [LAUGHS] Right. Yeah, there’s a, a wry reference to Harry Potter.

JULIE PHILLIPS: Mm-hmm. [AFFIRMATIVE] This series, you know, it’s a young adult series. She’s interested in how people form themselves, in how people make themselves. She wants to get people to look at the good and bad in themselves, to say, yes, I am all of these things, I can be a good person without being a perfect person. It’s about balance for her.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm.

JULIE PHILLIPS: That was a really important concept in her work.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And when she wrote the book Tehanu, the first one with a, a central female character.

JULIE PHILLIPS: She was not writing under a man’s name but she was writing from the point of view of male characters.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm.

JULIE PHILLIPS: And after her great mid-‘70s novel, The Dispossessed, came out, she started to feel that that had to change. That was a difficult time for her. She had to feel her way forward. She said her mother, even her mother said, why don't you write from a woman's perspective, and she told her mother, “I don't know how.”

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Was that a fairly chronological addition or did she returned to the series of Earthsea to write that?

JULIE PHILLIPS: No, she came back to it and then she completely rethought her fantasy world. She said, okay, this world, Earthsea, it's beautiful but there are some things wrong with it and I am going to set them right. And so, in Tehanu, she made the heroine a middle-aged housewife and thought about how that world would look like, from that perspective. Ten years later she wrote another book, The Other Wind, which brings the whole thing together. I've been thinking about that book a lot lately because there's a world of the dead in the Earthsea books. There’s a little wall of stones and you’ll go across and you're in the world of the dead where nothing ever changes and everything is silent and dry.

[CLIP/MUSIC UP & UNDER]

MALE READER: It’s gray and empty, the dry land, barren, no sunlight, unmoving stars, no grass or trees or wind. There are people moving around but they’re silent, untouching.

[END CLIP]

JULIE PHILLIPS: And in her last book she said, I don't want this to be the world of the dead, I want to dead to go free, I want them to be part of the living world. And the last scene is that the people of Earthsea break down the wall of stones and release the dead to become part of life again.

[BROOKE SIGHS]

It always makes me cry when I read it.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Isn’t that something that someone who is approaching the end of their years might imagine?

JULIE PHILLIPS: Yeah. You know, you’ve created this silent land as a young person without imagining that you, yourself, [PAUSE] that you, yourself, might one day, and so, you change it. She could go back and change her worlds. That was wonderful about her.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Let’s talk about the next world she created. My favorite of her books, The Left Hand of Darkness, plays with gender so brilliantly. You have humans who have been tinkered with genetically so that they only have periods when they assume a gender. The rest of the time they're neutral, and so when they see --

[BOTH SPEAK/OVERLAP]

JULIE PHILLIPS: That’s kind of like your period. It happens once a month.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: [LAUGHS] So when they meet humans, they seem so overripe and feral and --

JULIE PHILLIPS: Like perverts.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Yeah, like perverts. And, as you read it, you kind of start feeling that way yourself.

JULIE PHILLIPS: Mm-hmm. [AFFIRMATIVE]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And it was very important to some of the greatest writers of science fiction who are women of color who cite The Left Hand of Darkness for being about people who are brown!

JULIE PHILLIPS: Mm. She did it very subtly. She just described Genly Ai’s skin as brown, and then you were in his skin.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Yeah, because he is the surrogate for all humanity, as we know it --

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm. [AFFIRMATIVE]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: -- Earth-based humanity. And there was one writer in the essay called “Shame.”

JULIE PHILLIPS: Pam Knowles.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Pam Knowles, as a young child of color loved science fiction, she was as excited as if she'd won the

lottery --

JULIE PHILLIPS: Mmm.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: -- when she realized the people in The Left Hand of Darkness were brown. For me, it was the absence of gender that made that so revelatory.

JULIE PHILLIPS: Yeah, I think for indigenous people, for gay people and transgender people, she was hugely important in allowing them to envision themselves in the world.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: If she was looking at the systems imposed by gender and race and otherness in Left Hand of Darkness, she was world building and examining political systems in The Dispossessed.

JULIE PHILLIPS: She said at one point she realized that no one had ever written a pacifist anarchist utopia and --

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And how did it look?

JULIE PHILLIPS: Shevek, the hero, is raised in this egalitarian world and then he goes to the other world, this capitalist world, and we see it through his eyes as a place of more beauty, actually, than the world he's from but also of greater inequality. And he has to decide what's more important to him.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm. And part of what figures, I think, into his thinking is Taoism.

JULIE PHILLIPS: Yeah. I think it spoke to a need for emotional balance in her own life. It spoke to her sense that the best course of action in the world was to create balance, rather than to attempt change for the sake of change or to go rushing off in one direction or another. She once said that the basic plot of a lot of her books is the road to hell is paved with good intentions.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Among her many, many honors, in 2014, Le Guin won the medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters at the National Book Awards. This was 2014.

[CLIP]:

URSULA K. LE GUIN: I think hard times are coming when we will be wanting the voices of writers who can see alternatives to how we live now and can see through our fear-stricken society and its obsessive technologies to other ways of being. We will need writers who can remember freedom, poets, visionaries, the realists of a larger reality.

[END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: “The realists of a larger reality” could well describe her.

JULIE PHILLIPS: Yeah. Freedom was so important to her, and she was always thinking about what it meant. Nothing was ever a fixed concept for her. The tensions that she brings out in her work are very American, in a way tensions about the other, about alienation, about who we think we are and who we actually are, who we could be.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

JULIE PHILLIPS: Julie, thank you very much

JULIE PHILLIPS: Thank you.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Julie Phillips is a writer and book reviewer who’s long been at work on Le Guin’s authorized biography.

[CLIP]:

URSULA K. LE GUIN: Do you people realize, by the way, that to my three children science fiction is not a low form of literature involving little winged men and written by little contemptible hacks. It’s an absolutely ordinary respectable square profession. It’s the kind of thing your own mother does?

[AUDIENCE LAUGHTER AND APPLAUSE]