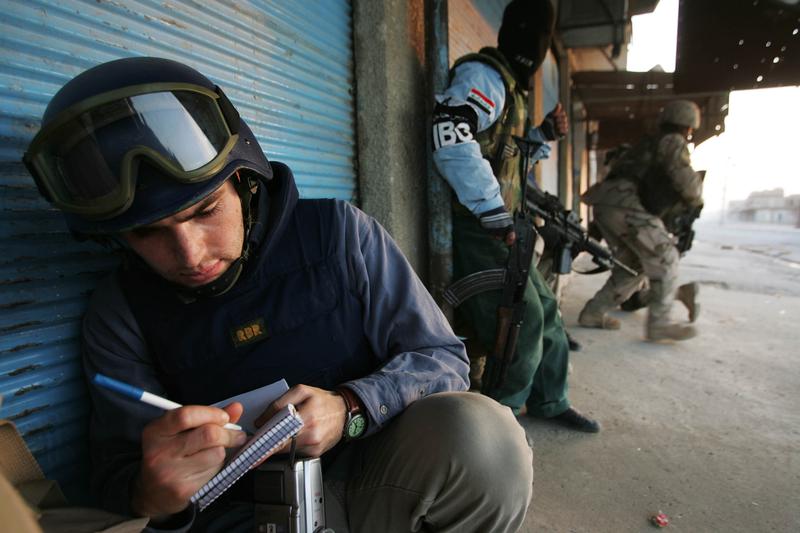

BOB GARFIELD: One year ago, the Department of Defense released its “Law of War Manual,” a first-of-its-kind comprehensive guide to wartime protocols. It was a landmark document, but within its nearly 1200 pages, one section stood out, at least to us, the one detailing the treatment of journalists in wartime. It suggested that field commanders could classify journalists as, quote, “unprivileged belligerents” and even treat them as spies. Last August, we spoke to the Defense Department’s General Counsel Charles A. Allen about the language, and he assured us that changes would be made. In January, we checked back in with Allen and Pentagon Press Secretary Peter Cook, who assured us that changes - would be coming very soon. And now, six months after that, we’re joined, once again, by Allen and Cook, and they have news. Gentlemen, welcome.

PETER COOK: Good to be with you, Bob.

CHUCK ALLEN: Great to be here, Bob.

BOB GARFIELD: The language that most raised eyebrows went like this: “In general, journalists are civilians. However, journalists may be members of the armed forces, persons authorized to accompany the armed forces or unprivileged belligerents,” which is, at best, open ended. How does the new section of the manual read?

CHUCK ALLEN: Bob, this is Chuck. We started out with a whole basic reorganization of the section on journalists. The previous version did not talk about first principles right up front, and it really should have. So it starts out with the fundamental that journalists are civilians, period. They are to be protected, as such.

On the issue of “unprivileged belligerent,” it makes clear that simply engaging in journalist activities does not make a journalist a target as an unprivileged belligerent. It does, however, preserve the concept that an unprivileged belligerent, that is, somebody who's, in the case of Al Qaeda, for example, fighting against the United States, that person would not be precluded from being considered an enemy simply because he or she is working as a journalist.

BOB GARFIELD: In other words, if some enemy was operating under its own media arm, let's just say, that does not accord them the benefit of the doubt. If you’re Al Qaeda, you’re Al Qaeda, whether you’ve got a, a press card or not.

CHUCK ALLEN: That’s right.

PETER COOK: And Bob, if I could, I, I would like to read in, in more detail exactly how this section begins because I do think it sets a, a different tone. And, as Chuck said, it begins:

“In general, journalists are civilians and are protected as such under the law of war." Journalists play a vital role in free societies and the rule of law and in providing information about armed conflict. Moreover, the proactive release of accurate information to domestic and international audiences has been viewed as consistent with the objectives of U.S. military operations. DoD operates under the policy that open and independent reporting is the principal means of coverage of U.S. military operations."

The manual in this section originally was intended, more than anything, to preserve the rights of journalists and to identify journalistic activities in a time of war. And yet, we’re not sure that the manual originally did that. We think this new updated version makes clear the rights, the protections for journalists, as opposed to, to any suggestion of what might undermine somebody operating as, as a journalist.

BOB GARFIELD: What was troubling, in particular about the original language, was that a field commander who had a burr in his saddle over some member of the press could have, if – depending on how he or she chose to read the manual, just treated an annoying gadfly reporter as a, a spy.

CHUCK ALLEN: Bob, and I remember that exchange that we had back in August on that or a similar hypothetical. I made the point that there was nothing in the manual that would give comfort to a commander that was considering such a, an outrageous decision. I do think that I don't think you could even construct that hypothetical out of the current version of the manual, the new one.

BOB GARFIELD: There was one other particularly nettling piece of language, a sentence that said, “To avoid being mistaken for spies, journalists should act openly and with the permission of relevant authorities,” which seemed to suggest that we can exercise our First Amendment rights only with the permission of the military. That has vanished in the latest draft?

CHUCK ALLEN: It has. Now you have the recognition that members of the press might very well be in contact with enemy personnel and - this is a quote - “efforts should be made to distinguish between the activities of journalists and the activities of enemy forces, so that journalists’ activities, e.g., meetings or other contacts with enemy personnel for journalistic purposes, do not result in a mistaken conclusion that a journalist is part of enemy forces.” And I, I hope you agree that that's a much better way to make that point, that we recognize that it’s a job that they need to do with confidentiality, and that includes talking to a whole host of people in, in every case –

[BOTH SPEAK/OVERLAP]

PETER COOK: Including, potentially, the enemy.

CHUCK ALLEN: Yeah, and in any case, we want to, to see them protected.

BOB GARFIELD: The whole tone towards journalism seems to have changed. In the, the language that you read, Peter, there was quite a shout-out to the First Amendment and its function. And there’s also, just in the headings, some language that suggests this is not an “us against them” proposition. You've removed the headings “journalists and spying” and “security precautions and journalists” and replaced them with much more anodyne language, such as, “journalists reporting on military operations,” which seems to be a lot more forgiving as to the role of the press.

CHUCK ALLEN: Bob, I would just say much more accurate, as well, frankly. We've gone to school and we, I hope, have listened, and it - it's been gratifying to me and I think to my colleagues to learn more about the profession, to learn more about the interchange.

PETER COOK: To be able to hear directly from reporters who have operated in war zones, who have operated embedded with US troops. It was very helpful for the legal folks here to be able to hear hypotheticals, even real-world situations that reporters had gone through to get a better understanding about why some of these words might be interpreted the wrong way. And I think it's a testimony to Chuck and his team that the finished product reflects so much of that input.

BOB GARFIELD: Gentlemen, I feel like we’re practically a coffee klatch at this stage, we talk so often, but thank you very much, once again, for joining us.

PETER COOK: Bob, thanks for having us and thanks for your interest and your input on this issue.

CHUCK ALLEN: Thank you very, very much, Bob. I appreciate it.

BOB GARFIELD: All right, thanks, guys. I appreciate it and the effort by the DoD.

CHUCK ALLEN: Had you not really pressed early for this, even before Peter took office, I think that was a real catalyst to us, and we tribute you.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Coming up, a Breaking News Consumers Handbook, Coup Edition.

BOB GARFIELD: This is On the Media.