BROOKE GLADSTONE: This is On the Media. I’m Brooke Gladstone.

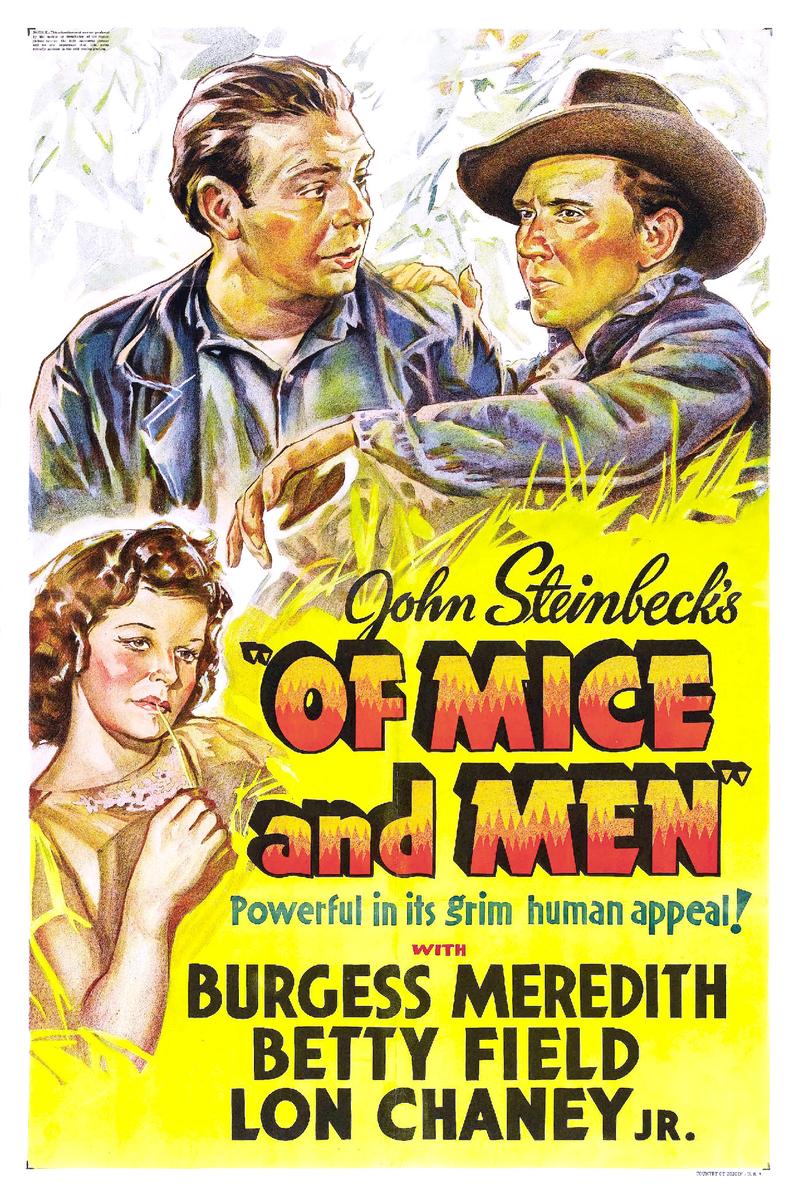

BOB GARFIELD: And I'm Bob Garfield. We learned recently that music lyrics, at least as defined by the Nobel Prize Committee, can be deemed literature. This term, the US Supreme Court will consider whether literature can be the basis for law. The case, Moore v. Texas, will take up whether the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals violated the Eighth Amendment and judicial precedent by using outdated medical criteria and a fictional character as a test for real-life capital cases. That character is Lenny, the intellectually disabled killer from John Steinbeck's Of Mice and Men.

[CLIP]:

GEORGE MILTON: You can’t keep a job, you get in trouble, you do bad things and I got to get you out all the time.

LENNIE: You want I should go away and leave you alone?

GEORGE: Where could you go?

LENNIE: Oh, I could... I could go right up in them hills and some place find a cave.

GEORGE: How'd ya eat? You aint' got sense enough to find somethin' to eat.

[END CLIP]

BOB GARFIELD: The Texas Court rules that in determining culpability for murder by low-IQ defendants, a “Lennie Standard” should apply. Adam Liptak covers the High Court for The New York Times. Adam, welcome back to the big show.

ADAM LIPTAK: Good to be here, Bob.

BOB GARFIELD: The “Lennie Standard”?

ADAM LIPTAK: When I first saw it, I thought it was a reference to some old legal precedent, but it turns out to be a reference to a fictional character that the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals, its highest court for criminal matters, said is a touchstone for deciding who should and should not be subject to execution.

BOB GARFIELD: And it's a checklist. Can you give me the highlights?

ADAM LIPTAK: Has the person formulated plans and carried them through or is his conduct impulsive?

[CLIP]:

SLIM: I guess Lennie done it all right or – her neck’s bust.

Lennie could have done that?

ADAM LIPTAK: Lennie committed murder but impulsively.

SLIM: Well, I guess we ought to get him.

GEORGE: Couldn’t you bring him in and lock him up? He’s nut. He never done this to be mean.

ADAM LIPTAK: Or –

GEORGE: What did you take out of that pocket?

ADAM LIPTAK: - can the person hide facts or life effectively?

LENNIE: There’s nothing in the pocket, George.

GEORGE: I know it ain’t, you got it in your hand. Now, what you got in your hand?

LENNIE: No, that – that’s my mouse. But I didn’t, I didn’t kill it, George, honest, I found it dead.

[END CLIP]

ADAM LIPTAK: And it was these kinds of takeaways about Lennie’s character that made their way into Texas law.

BOB GARFIELD: Now, if you look at the whole list, they seem like pretty good questions to be answered in evaluating whether the defendant really knew what he was doing when he committed the crime. On the other hand, there was a pretty established body of law, including [LAUGHS] an entire amendment to the Constitution that covered this issue. You know, I'm wondering what about the existing law, including Supreme Court precedent Judge Cathy Cochran deemed wanting.

ADAM LIPTAK: The Supreme Court in 2002 said we’re going to categorically bar the execution of the intellectually disabled under a more conventional three-part test. It looks to IQ, looks to whether they can take care of themselves, can conduct the normal business of life, have what, in legal terms, they called “adaptive functions” and whether these qualities appeared before the person reached age 18. So there was that three-part test. The Supreme Court established it.

At the same time, in 2002, it told the states, listen, we’re not going to micromanage this. You guys will have substantial leeway. And the question now for the justices is whether Texas’s application of that standard, partly based on this discussion of Lennie and partly based on the fact that the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals recently has said that it's okay to look at outdated medical standards, standards from 1992, as opposed to more contemporary ones in deciding whether this inmate should be executed.

BOB GARFIELD: Tell me about the subject of this case, Bobby Moore himself.

ADAM LIPTAK: Bobby Moore had a very hard time in school, eventually took to the streets, ended up, as a young man, killing James McCarble, a 70-year-old grocery clerk in 1980 in Houston. So when a state judge conducted a hearing not long ago about whether Mr. Moore was or was not intellectually disabled, he took into account his IQ, which has been measured several times and it's gone as high as 78, as low as 57, averaging around 70, which is roughly where the Supreme Court says that intellectual disability starts, as a general matter. And he looked at how good he was at things like telling time, knowing what day of the week it is. And those were things that Mr. Moore can't handle.

On the other hand, the state says the way he committed the crime, by putting on a wig and hiding a shotgun in a plastic bag, is evidence that he is intellectually capable. And that as a boy he played pool for money, he mowed lawns for money, showing that he has adaptive skills. So there was evidence on both sides, but it's a close question. And the state court trial judge says using contemporary medical evidence, he’s going to spare Mr. Moore from execution. The Texas's highest court says different, says, we’re going to look at older medical standards, we’re going to put Mr. Moore back on death row.

BOB GARFIELD: What makes this a bit more complicated is that the sort of textbook approach to determining whether somebody is too intellectually disabled to be held responsible for murder is based on the DSM, which, itself, is, I guess, not exactly arbitrary, but you cannot do a blood test or an MRI for this issue. It is itself a consensus, an ever-changing consensus of mental health professionals. So is this a case of the rather squishy DSM versus the rather squishy Lennie Standard?

ADAM LIPTAK: That's a good way to think about it. When the Supreme Court said you can’t execute juveniles, all you needed to do was figure out if someone was over or under the age of 18 when they committed their crime. When you say you can't execute the intellectually disabled, it’s a much tougher bright-line test. And the justices are struggling with and the Texas attorney general is telling them that, listen, you’ve got to give us some leeway, you can't outsource this entirely to medical professional associations who are generally opposed to the death penalty and who may be fashioning their standards in a way to make it harder to execute people and that if there's an evolving standard of decency, as the Court has said, in the application of the Eighth Amendment’s bar of cruel and unusual punishment, it needs to be a societal standard, something that everybody agrees about and not something you outsource to a medical group.

BOB GARFIELD: Finally, John Steinbeck himself is long dead but his son, before he died, weighed in on question. What did Thomas Steinbeck have to say?

ADAM LIPTAK: Thomas Steinbeck was furious on behalf of his dad. He said [LAUGHS] the character of Lennie was never intended to be used to diagnose a medical condition like intellectual disability. You hardly think that sentence needs to be uttered but, you know, we’re in Texas. Steinbeck continued, “I find the whole premise to be insulting, outrageous, ridiculous and profoundly tragic.” And John Steinbeck, as you know, Bob, was a complicated character, and what his son said about him was, “I am certain that if my father, John Steinbeck, were here, he would be deeply angry and ashamed to see his work used in this way and the last thing you ever wanted to do was make John Steinbeck angry.”

BOB GARFIELD: [LAUGHS] Adam, as always, thank you very, very much.

ADAM LIPTAK: A pleasure to be here. Thank you.

BOB GARFIELD: Adam Liptak covers the US Supreme Court for The New York Times.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Coming up, our last episode in “Busted: America’s Poverty Myths.” This is the epilogue in which we present “The Breaking News Consumer’s Handbook” to poverty coverage.

BOB GARFIELD: This is On the Media.