Kurt Vonnegut and the Shape of the Pandemic

( Kurt Vonnegut / Youtube )

BROOKE GLADSTONE This is On the Media, I'm Brooke Gladstone. We've discussed the words that soothe us, the mistakes that alarm us. What about the numbers? Those cannot fail to move us with their cold, hard truths.

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT There have been nearly 238 million cases worldwide since the pandemic began and more than 4.8 million deaths. [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE How does that figure make you feel? Shock, sorrow, anything? COVID is still too much with us, and yet many of us are just too spent, too confused to react anymore. Maybe we've simply reached a limit. On the Media correspondent Micah Loewinger looked to the work of one of fiction's greatest practitioners to make sense of how and why we lost the plot.

MICAH LOEWINGER The other day, I was talking with my friend Soren Wheeler, he also works at WNYC, about the dissonance of this moment in the pandemic.

SOREN WHEELER I ran into a neighbor friend after dropping our kids off at school. I have a six year old who's not vaccinated, so like, it's definitely not over for us. She's like, 'Oh, are you guys still worried about that?' And I was like, shocked. But also, I didn't have a dramatic answer to 'are you still worried about it?' I had to be like, 'Well, not really for me in terms of hospitalization because I'm vaccinated and the kids, it's not as big a risk to them and my parents are good and like, but I but I just don't want it to keep going in case there's another mutation.' Even my dramatic feelings that it's not over were sort of abstract and flatter and slower.

MICAH LOEWINGER It's interesting to me that Soren was drawing a blank because he's one of the people most up for the challenge. He's the editor at Radiolab, where he thinks a lot about making hard topics accessible and engaging.

SOREN WHEELER Many of us don't think we want to hear about science, or many of us don't think we want to hear about politics or economics, or just like sort of a dark, dark thing, like a drone strike or something that you're just feel like, 'Oh, I don't want it.' And if you just give people information, you're never going to beat that feeling. That the way to beat that feeling, and make people engage with information, the lubrication to get them to get a new idea into their brain is emotion and emotional change over time.

MICAH LOEWINGER Of course, not all emotional stories are captivating, it's more complicated. Our own standards are mysterious to us. But several years ago, Soren found a sort of cheat code for how to distinguish good stories from bad ones. When he clicked on this esoteric YouTube video of an old lecture.

[CLIP]

KURT VONNEGUT Where the hell are we? [END CLIP]

MICAH LOEWINGER This is novelist Kurt Vonnegut, the author of Slaughterhouse Five, Cat's Cradle, and so many other great books.

SOREN WHEELER Vonnegut is a hero of mine, and then at some point I stumbled into this video and it just unveiled something. It's wry and funny, but also just deeply revealing about some basic things about us.

[CLIP]

KURT VONNEGUT No reason why those simple shapes of stories can't be fed into computers. They are beautiful shapes. [END CLIP]

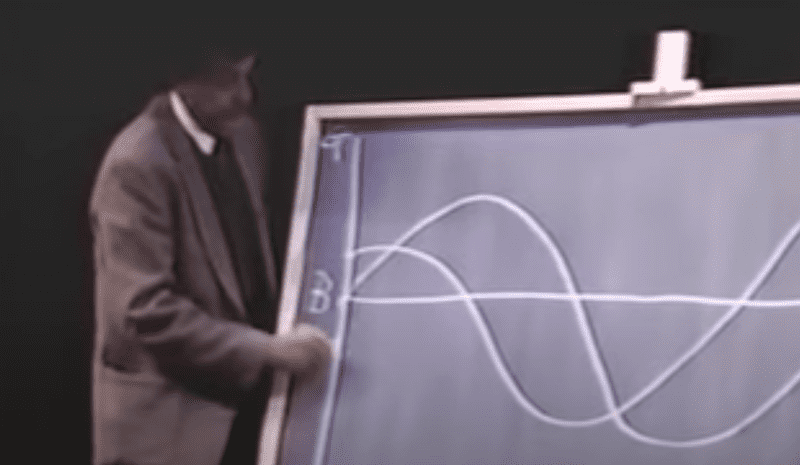

MICAH LOEWINGER The lectures about a theory he had about the geometrical shapes of stories, really popular stories. Ones we've heard a billion times.

SOREN WHEELER He's like, sort of like a somewhat curmudgeonly, cynical old, oldish man by this point, and he's on a stage in sort of one of his sloppy suits and he's got a chalkboard.

[CLIP]

KURT VONNEGUT This is the G.I. axis. Good fortune. Ill fortune. Sickness and poverty down here. Wealth, and boisterous good health up there. [END CLIP]

MICAH LOEWINGER Vonnegut draws two perpendicular lines: a simple x y axis on the chalkboard. The first line is labeled G for good fortune on the top left corner and I for ill fortune on the bottom left corner. And slicing through the middle of the chalkboard, left to right, is the second line the x axis.

[CLIP]

KURT VONNEGUT Now this is the B-E axis. B stands for a beginning, E stands for electricity. [END CLIP]

SOREN WHEELER Just starts explaining, there's just a couple of stories out there. He names the first one 'Man In A Hole'.

[CLIP]

KURT VONNEGUT Call, the story Man in Hole, but it needn't be about a man, and it needn't be about somebody getting into a hole. It's just a good way to remember it. Somebody gets into trouble, gets out of it again. [END CLIP]

MICAH LOEWINGER In one motion, he draws a single curve with a shallow tip showing the person's fortune dropping down and swooping back up.

[CLIP]

KURT VONNEGUT People love that story. They never got sick of it. [END CLIP]

SOREN WHEELER It's just like, 'boom,' like what I'm doing in my head is like, 'Oh my god, yeah,' that's a whole category of movie that I've seen a thousand times.

MICAH LOEWINGER A 2018 study from Birmingham University used A.I. to analyze over 6000 scripts and found that this is the most profitable arc in all of Hollywood. And when you think about it, there are so many movies that are basically 'Man In A Hole' stories.

SOREN WHEELER Bill and Ted's Excellent Adventure is that.

MICAH LOEWINGER That's a great one. And Harold and Kumar Go to White Castle.

SOREN WHEELER Sure, yeah.

MICAH LOEWINGER Harold and Kumar, average day, they decide they want to get food.

[CLIP]

KUMAR No matter what, we are not ending this night without White Castle in our stomachs. Agreed?

HAROLD Agreed. [END CLIP]

MICAH LOEWINGER And then they go on a crazy journey, and it seems like all hope is lost after they're like stuck in the woods and everything has gone to crap.

[CLIP]

HAROLD I'm completely on edge right now, man. After all that sh*t that we've been through tonight, I don't know how much more I can take. [END CLIP]

MICAH LOEWINGER And then they managed to find the courage and some crazy, serendipitous events leads to them finally getting to White Castle, getting their burgers.

[CLIP]

WHITE CASTLE Looks like you guys had some night, huh?

HAROLD I want 30 sliders, 5 french fries and 4 large cherry Cokes.

KUMAR I want the same, except make mine Diet Cokes. [END CLIP]

MICAH LOEWINGER And so not only do they emerge from the hole, but they're sort of stronger afterward.

SOREN WHEELER You can see on the curve like that the man in the hole ends up higher up than where he or she started, right?

MICAH LOEWINGER Anyway, back to the lecture, Vonnegut begins drawing a second curve, which he calls...

[CLIP]

KURT VONNEGUT Boy gets girl, but it needn't be that. Just a way to remember it. Start on an average day, average person not expecting anything to happen a day like any other. Find something wonderful. Just loves it. [END CLIP]

MICAH LOEWINGER Vonnegut draws a curve with an upward slope. The protagonist has found their true love, but then the incline reaches a rounded peak. The moment when the protagonist and we, the audience realize this is all way too good to last.

SOREN WHEELER And then it goes bad. They lose it almost always, because to get the person they love, they'd like made up some stupid lie, or they said they were somebody they weren't. They go down and they lose the girl.

MICAH LOEWINGER Our character is heartbroken, and Vonnegut's curve drops down to a deep low on the good slash ill fortune axis. But then -.

SOREN WHEELER Usually in the last five minutes of the movie, they get the girl or the boy back and they're happy.

MICAH LOEWINGER And so the curve shoots way back up to finish the story. Vonnegut's curve ends up looking like an 's' flipped on its side. Neutral to happy, to sad, to happy again. People like that. Vonnegut's next story, he tells us, is a little bit more complicated.

[CLIP]

KURT VONNEGUT We love to hear this story. Every time it's retold, somebody makes another million dollars. You're welcome to do it. We're going to start way down here. Who is so low? It's a little girl. What's happened? Her mother has died. Her father has remarried. A vile-tempered, ugly woman with two nasty daughters, big daughter.

[LAUGHING CONTINUES UNDER]

SOREN WHEELER So Cinderella.

MICAH LOEWINGER Yeah.

KURT VONNEGUT Anyway, there's a party at the palace that night, she can't go. OK, so the fairy godmother comes. Gives her shoes, gives her stocking, gives her mascara, gives her a means of transportation, goes to the party, has a swell time. [END CLIP]

SOREN WHEELER This is the first time that, like you notice that he's introducing a whole nother aspect into these curves, which is slope. Because if you're going from beginning, middle and end, then what you're dealing with this time is so how steeply it goes up has to do with how fast it happens. Fairy Godmother comes along and he does this little staircase thing he's like.

[MUSIC BEGINS IN CINDERELLA TRANSFORMATION]

SOREN WHEELER Gives her some mascara, gives her some shoes, gives her a dress. Boom, boom. Hits of good fortune in this little staircase. And then she goes to the ball. And so now she's up, crossing past the line and up into the happy zone, dancing with the prince.

[CLIP]

CINDERELLA So this is love. mhmmhmm So this is love... [END CLIP]

SOREN WHEELER So, yeah, yeah. And then he does this thing where the line starts going down and he goes dong dong.

[CLIP]

KURT VONNEGUT Brrring, brrring, brrring. Now there's a slight inclination to that line, as I've drawn it because it takes perhaps 20 seconds, 30 seconds for a grandfather clock to strike 12.

[CLIP]

HANDSOME PRINCE Oh no, wait, you can't go now. It's only--

CINDERELLA Oh, I must, please, please I must.

[FADES INTO NEXT CLIP]

KURT VONNEGUT Does she wind up at the same level? Of course not. She will remember that dance for the rest of her life. Now she pooped along on this level till the prince comes, the shoe fits, she achieves off-scale happiness.

MICAH LOEWINGER Vonnegut's curve shoots to the top right corner of the chalkboard. And then he draws a little infinity sign.

SOREN WHEELER That is every fairy tales last line, which is ‘and they lived happily ever after,’ you know?

MICAH LOEWINGER Now, obviously, not all good stories need to have a happy ending. There are many different types of narratives out there. These just happen to be a few of the most popular ones, the ones that put a spell on us.

SOREN WHEELER The whole thing is like, look how simple we are. People never get sick of it. Our brain wants that over and over and over and over again. Like our brain still scans it as unexpected. We saw something go from good to bad and then good again?

MICAH LOEWINGER And maybe that sounds a little depressing to think that we're kind of trapped in this cycle of paying to see and feel that emotional experience playing out over and over. Trapped by a desire for that repetition, that familiarity. But Soren thinks it's actually quite instructive. For him and the producers at Radiolab. These are blueprints for how to satisfy and sustain a listener's attention and blueprints for what not to do.

SOREN WHEELER I mean, I always used to argue that like, I don't think Radiolab has ever said yes to a story that crossed the line once.

MICAH LOEWINGER So just one turn of fortune?

SOREN WHEELER Right. Like, Oh, here's Mary, she was super happy and going along, and then she got an illness and got really sick. And if you just leave me down there, man, I'm like, Oh, why did I listen to this? There's just a level of complication below which it didn't feel worth it.

MICAH LOEWINGER But it also seems like the opposite can be true. What happens when there are too many changes in fortune?

SOREN WHEELER Oh, sure. If you go up and down and up and down and up and down and up – by right around here, you've lost any element of surprise, probably. You've also sort of lost the feeling that we're on a path to something that there's an end point of any kind, which is the whole reason we listen to stories is just to get to an end point and then have a thought or feel different afterwards. You've lost the idea that there's any meaning to be made out of this.

MICAH LOEWINGER Yeah, you're going to numb their receptors.

SOREN WHEELER Right, yes.

MICAH LOEWINGER You know, I also encountered this video. I was binging Vonnegut's books, and then I started listening to old interviews with him on YouTube, and that's how I came across this video. And once I saw the shapes, they were kind of burned into my mind.

SOREN WHEELER Right.

MICAH LOEWINGER Then when the pandemic hit, there was this moment where the shapes of the pandemic became a universal language.

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT Flatten the curve, flatten the curve. We did it. We flattened the curve.

NEWS REPORT We didn't just flatten the curve. We bent the curve. [END CLIP]

SOREN WHEELER I'm right there with you. It was completely striking, and I was instantly thinking about all the curves, both literal in terms of the rise of cases, but also like a pandemic as a story, right? A pandemic should have a beginning, middle and end as COVID is rising. What we're doing is we're plummeting down Vonnegut's line, down from health and wealth, down into like poverty and sickness and death.

MICAH LOEWINGER And when the daily cases began to drop at the end of that first wave last year, the emotional tenor of the country and the coverage seemed to improve too. At least for a moment.

[CLIP MONTAGE]

NEWS REPORT Northern New York state today, the governor saying all indications on the medical front continue to be encouraging hospitalizations down, new COVID cases down.

NEWS REPORT There is some good news, some sparks of hope. We're seeing cases falling, hospitalizations down...

NEWS REPORT Case numbers are going up, they're going up. 40 states are showing COVID rates that are going up.

NEWS REPORT New numbers this morning are pointing to a brighter picture in the U.S., the national rate of new COVID 19 infections and hospitalizations, both of those numbers are going down. [END MONTAGE]

MICAH LOEWINGER If you pull up a graph of the pandemic, you can see this ebb and flow of cases along the rippling Vonnegut curve.

SOREN WHEELER Up and down and up and down and up and down.

MICAH LOEWINGER Yeah, but I don't know, is that a good story?

SOREN WHEELER No. I mean, why are you asking that question? You know, it's not a good story.

MICAH LOEWINGER I know it's not a good story, but I'm just trying to make the point.

SOREN WHEELER Yeah, no. It's a bad story. Yeah, nobody wants to hear that story. I wouldn't put that story on the air. I wouldn't go to a movie theater to watch that story.

RACHEL PILTCH-LOEB I guess from my perspective, it's been a little bit of a sad and terrifying story.

MICAH LOEWINGER That's Rachel Piltch-Loed preparedness fellow at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

RACHEL PILTCH-LOEB It's a scary story from the perspective of what does it mean for our public health infrastructure? What does it mean for the next time this comes around?

MICAH LOEWINGER I want to see if this made sense from a kind of epidemiological perspective. So I sent her an email summarizing my conversation with Soren about the pandemic, and Vonnegut's shapes

RACHEL PILTCH-LOEB I conceptually liked the thought a lot. I mean, the idea that we, as humans have narrative filters that we put on the world. And I think one of the challenges of the pandemic has been, we don't really know the trajectory of what's going to happen.

MICAH LOEWINGER Were there moments where there may have effectively been an over promise or where people may have perceived an imminent end to the pandemic?

RACHEL PILTCH-LOEB What was presented as a turning point in the story nationally was the vaccine availability and rollout, and we basically came up with a policy that was not necessarily founded in a particular piece of evidence besides the desire to make it true, which was if you're vaccinated, no other public health measures are necessary. Then we were faced with the Delta variant and people thought that the story had ended, so to speak. Vaccines are rarely 100 percent effective at preventing merely infection. That's not what they're designed to do. They're designed to prevent the impact of the infection, which is certainly what these vaccines do. We then had to start retelling a new set of policies, a new set of explanations, etc. And I think that that pivotal time really is where more people were lost and kind of began down their own path of 'I'm going to try and figure out what works for me'.

MICAH LOEWINGER We lost the plot.

RACHEL PILTCH-LOEB Yeah. It created this perception that the vaccines were the savior in the story, right? Our expectations of it were not realistic because the reality is that there is no panacea for a pandemic.

MICAH LOEWINGER Yeah, and I would say that that's probably not even unique to a pandemic or any kind of public health crisis. I mean, it's funny when we use terms like national narrative or whatever. When we watch a movie, we can take away different conclusions, but we're all watching the same movie. You know, we're all reading the same book. And one place where maybe my theory breaks down and where it's not so analogous is that we're not really witnessing the same story.

RACHEL PILTCH-LOEB We're talking about kind of a global story, a national story, a community story and a personal story, meaning my experience is probably pretty different from from yours or from somebody else who's had a different experience personally with the virus, who maybe lives in a different part of the country, certainly in a different part of the world. So this story is still ongoing. We need to look really introspectively to figure out how to change the story for the next time.

SOREN WHEELER As much as like the simple stories are crack for the human brain, there's got to be a way to making us all a little bit more friendly to like the complicated stories and make complexity something to be revelled in and curious about, and fun and not dangerous or whatever. Or at least just recognize that none of the stories in our lives do the Vonnegut thing right? That's what we got to the movie theater for, but have a different version of us, a different habit of mine that we apply to the life around us, and especially to questions of public good.

MICAH LOEWINGER I'd like to end with a piece of advice that Vonnegut often used to tie up his lectures, something he learned from his uncle Alex.

[CLIP]

KURT VONNEGUT What Uncle Alex found objectionable about so many human beings is that they so seldom noticed it when they were happy. And so we would be sitting under an apple tree, for instance, on a July afternoon drinking lemonade and practically buzzing like honey bees and uncle Alex would stop everything and say, Wait a minute, stop. If this isn't nice, I don't know what is! [END CLIP]

MICAH LOEWINGER We've spent this hour focused on the words that medicalised our hopes and fears and the tragic histories of life saving breakthroughs. It's been a messy narrative with no chance of ever ending up like Cinderella in that zone of infinite bliss. But as Vonnegut observed, some of the best stories don't make that landing and don't need to. As we watch our current storyline rise and fall and rise and fall, I'm thinking Uncle Alex may be pointing to the best ending we could ask for. For On the media, I'm Micah Loewinger.

BROOKE GLADSTONE On the Media is produced by Leah Feder, Micah Loewinger, Eloise Blondiau, Rebecca Clark-Callender and Molly Schwartz, with help from Juwayriah Wright and WNYC Archivist, Andy Lanset. Our technical director is Jennifer Munson. Our engineer this week was Adriene Lily. Katya Rogers is our executive producer. On the Media is a production of WNYC Studios, I'm Brooke Gladstone.