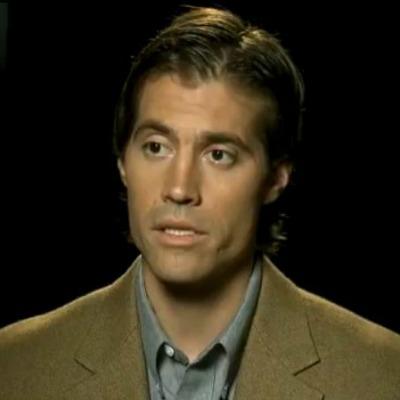

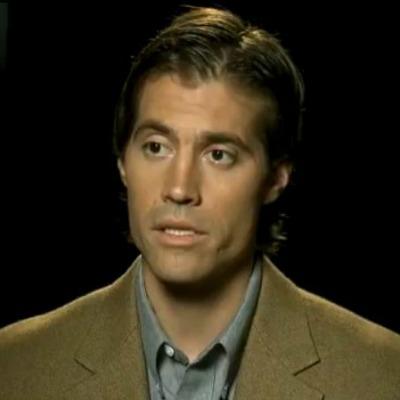

BROOKE GLADSTONE: It was on Tuesday just before 5pm, when the first mention of video showing the beheading of an American journalist, James Foley, surfaced on Twitter. Foley had disappeared in Syria in 2012 while working for the Boston-based online news organization, Global Post. The first tweets came from a journalist named Zaid Benjamin, Washington correspondent for Radio Sawa, who noted the existence of the gruesome video titled “A Message to America” purportedly from the group formerly called ISIS and now calling itself “Islamic State.” He didn’t link to to it but Twitter blocked his account anyway. Over the next hour, as Twitter administrators played whackamole with extremists who wanted the video to be seen, something extraordinary was happening among Twitter users.

The hashtag #ISISmediablackout, exhorting tweeters not to share the video or images from it, sprung up and immediately went viral; within an hour it was trending around the world in cities from Washington DC to Paris. Shane Harris has been following this, and the ISIS media campaign generally for Foreign Policy. Welcome back to On the Media.

SHANE HARRIS: Hi, Brooke. Thanks for having me.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: You're aware of the Twitter feeds operated by Islamic State supporters. Did they get involved in anyway with the conversation about the James Foley video, on Twitter?

SHANE HARRIS: They did. In fact there were two Twitter accounts that we know of that were suspended on Monday. The day before the video went up. And on Tuesday, they were up again. The same individuals under different accounts or different handle names. And they were promoting the video with celebratory kind of rhetoric. Revelling, I guess, in Foley's death.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And then some of these ISIS supporters on Twitter deactivated in advance. There was one tweet by someone called @mujaheedforlife which said: Guys, deactivate now.

SHANE HARRIS: It's a very interesting strategy. It sort of is a way of jumping back into the fog almost. And I think that these people who are running these accounts are very well aware of that fact that Twitter is trying to chase them down and deactivate them. You know I've talked to people over at Twitter. They're loathed to reveal how many people they have trying to police this content, but I gather that it's not many. And so really it's kind of a losing battle for them. Just, I mean, it was almost impossible to control the spread of this video. In fact, even before people were using the hashtag people were encouraging others to stop retweeting it and to stop talking aobut it. People saying, "I've seen the video. Don't watch it." Or people saying, "Don't retweet this. Don't promote it. That's what the Islamic State wants." To almost try and smother the fire before it spread.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: The first hashtag evidently came from this woman Libya Liberty and she said, "You know what I think? And I know how crazy this sounds, but we need an #ISISmediablackout. Amputate their reach. Pour water on their flame." Have you ever seen this sort of thing play out on social media before?

SHANE HARRIS: I've never seen it play out this extensively. I mean every now and then you'll see people saying, "Don't retweet jihadi propaganda videos, it's just what they want." But never this kind of organized fashion, with a hashtag and people sort of jumping on this bandwagon and saying enough is enough let's fight them back right now.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: I think it's remarkable because it's journalists that are calling for this kind of forbearance and it seems like you don't agree with it.

SHANE HARRIS: Yeah, I don't agree with it really. I mean I completely understand the passion in this case. Because, you know, James Foley was a journalist and journalists take that very personally. I mean, it's one of our own. But our job is to report. I think that you can report on the murder of James Foley without crossing the line into graphic or even arguably obscene imagery.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And by crossing the line you mean what the New York Post did.

SHANE HARRIS: Absolutely. I mean, printing photographs of a man in the seconds before he is about to be brutally killed crosses the line. You don't need to do that to convey to readers what happened and to explain to them how this fits into the Islamic State's overall propaganda campaign. I think pretending that it's not happening or trying to shut them down, I understand the intention of trying to fight back, but as journalists I think we have to fight against that instinct even in this case when everything is telling us, "Ignore it. Fight them somehow," I mean, it gave us a sense of power to be able to fight back at these guys who are trying to, in a sense, play in our wheelhouse. They're trying to create a media strategy.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And you said that this ISIS media blackout campaign has had at least as much impact as the attempts of governments.

SHANE HARRIS: Yeah, I think more so. I mean governments can only do so many things. These sort of draconian measures that the Iraqi government has taken, trying to shut off internet access in parts of their country. Or limit people's access to Twitter and to other social media platforms. That's never going to work. It hasn't worked. This, though, is something very powerful. This is spontaneous. It's the users of that platform standing up and fighting back. And I think it's fascinating and notable but as journalists I think we have to resist it.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Now, I wonder if you aren't, if you'll forgive me, conflating a couple of things here. And you can straighten me out. Because, if we can stipulate at least for the basis of this conversation that this kind of strategy can work. As I looked through the tweets what they were saying was, "Don't retweet, don't spread around the screenshots," they're not saying "Don't report on their media strategy."

SHANE HARRIS: That's true. And I'm reading a tweet even right now that say, "Report the news but starve ISIS of the publicity oxygen that they crave. Focus on the victims." And I think this raises the question of so how do we treat even James Foley himself, right? I mean, drawing a line of not posting the photos of him from the video is a good one. You saw this counter campaign come up of posting photos of him from a happier time.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: This was a new tactic to beat back those horrific images of his last moments. Trying to reclaim the Foley that we will remember by pictures of him on the job. Pictures of him calm. This is a fascinating attempt by colleagues of Foley, journalists, to seize and reshape the narrative.

SHANE HARRIS: It absolutely is. And I suspect that we will see this again. If this tragically befalls another journalist. And I think it's very smart, honestly. It's a way of pushing back and at the same time engaging in the story and changing that narrative. And that has taken off, it seems to me, as much as the ISIS media blackout idea. And they've kind of joined forces. I mean, there are tweets that will see ISIS media blackout, here is a pic of James Foley and will show a picture of him from an earlier time.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And the fact that it's effective makes it even better. All you have to do is acknowledge your own role in this sort of ecosystem and act responsibly and appropriately. Don't retweet something. You're not a machine. Add something that changes just a little bit the narrative that's going around. If journalists can do this than anybody can do this. To me, I mean it's horrible, but it's, it's kind of thrilling that it is possible that it is possible to take back some of that power.

SHANE HARRIS: I think what you're seeing in a moment like this is the creation of a body of ethics for how we behave in social media, which increasingly is such a huge part of how we communicate and consume news and information. It's just been a very powerful example of how really on-the-fly people can make up the rules for behavior and how we treat one another in this social space. And at the same time condemn people like the Islamic State for they way that they're using it.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Shane, that you very much.

SHANE HARRIS: My pleasure. Thanks Brooke.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Shane Harris is a senior staff writer at Foreign Policy and it the author of "At War: The Rise of the Military Internet Complex" out in November.