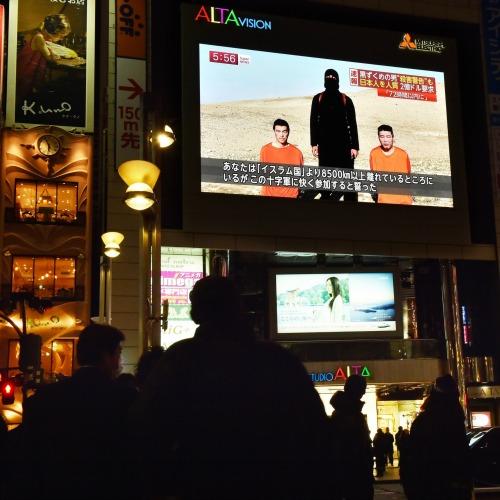

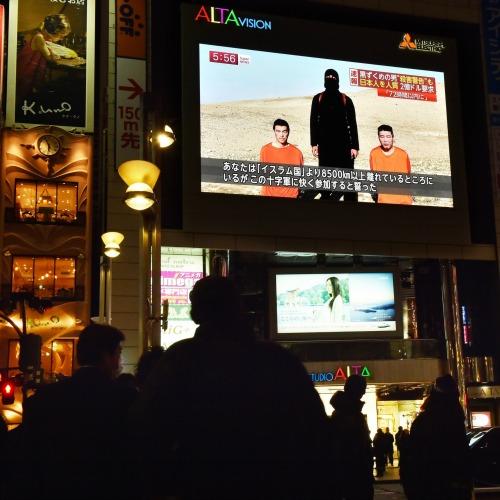

BOB: On Tuesday, an ISIS video surfaced online with the all-too-familiar trappings: a bleak desert backdrop and captive men jumpsuited pointedly in “Gitmo” orange, kneeling next to a masked figure wielding a knife. For the first time, though, the hostages were Japanese citizens:

ISIS CLIP: To the Japanese public. Just as how your government has made the foolish decision to pay 2 hundred million to fight the Islamic state, you now have 72 hours to pressure your government in making a wise decision by paying the 2 hundred million to save the lives of your citizens.

BOB: The 72-hour countdown was set to expire on Friday afternoon, Japan time. Several hours before the deadline, an ISIS spokesperson allegedly told a Japanese state news outlet that a statement was coming soon. Later, another video -- not officially from ISIS -- was released, showing a clock counting down to zero alongside images of previously beheaded hostages. But the deadline stipulated in the initial video has passed, and as of this writing, on Friday afternoon, 1 Eastern Standard, the fate of the two Japanese captives remains unclear.

BROOKE: On Thursday afternoon, before the deadline had elapsed, I spoke with Roland Kelts, a writer who divides his time between Tokyo and New York. He says that the ISIS video was all over Japanese media almost instantaneously.

KELTS: There's a great deal of anxiety in the media coverage. They don't want to be critical of anyone, whether it's the Japanese government or ISIS. They don't want to put these men at greater risk.

BROOKE: Tell me about these two captives. They've received very different reactions from the Japanese public, right?

KELTS: Exactly. And their backgrounds are very different. Kenji Goto who's the journalist, has been reporting from war zones since the 1990s. He commands a great deal of respect amongst journalists in Japan. People view him as someone who was doing a job, and doing it very bravely but not recklessly. Now this other guy, Haruna Yukawa, he basically went off the rails.

BROOKE: He's been described as a private security contractor.

KELTS: Yeah, sort of a self-styled soldier of fortune. His wife died of lung cancer in 2013. Thereafter he lost his job, and his home, and he took off for the Middle East allegedly to learn about military operations, he said, so that he could help the Japanese military. He's being viewed with great suspicion overall by the Japanese public.

BROOKE: Now, back in October, apparently, Goto recorded a video on a cell phone.

KELTS: He states in Japanese and in English that he takes full responsibility, that whatever happens to him, the people of Syria should not be blamed.

Goto Clip: So it is my responsibility, if something happens please don't have a bad impression to the Syrian people. Syrian people suffering three years and a half - it's enough.

KELTS: And there's a backstory to this which is that in 2004, three japanese hostages were released in Iraq and sent home. They were treated harshly by the Japanese public and media.

BROOKE: These were aid workers.

KELTS: These were aid workers and they were quite young, and they were seen as irresponsible, selfish, there's a term "okami," what we might call hubris. They actually went into hiding after they returned. A psychologist who was treating them said that the trauma of being abducted was actually less powerful than the trauma they experienced returning home and being shamed.

BROOKE: Why would the reaction be so harsh?

KELTS: I think it's difficult perhaps for Americans to understand the cultural paradigm that most Japanese sustain, which is that Japan is not the police nation of the world. Japan has not been engaged in any kind of military activity that you would call "warfare" since the end of World War 2. And a lot of the Japanese are very proud of that record of pacifism. Proud of the development of Japanese society economically, technologically. So for Japanese citizens who have everything provided for them by the society, by the culture, to run off into a military conflict in which Japan wants no part, and then for those individuals to ask for help from the Japanese government and people and financial support, and putting other people's lives at risk, is seen as intolerably selfish by many Japanese.

BROOKE: Well, let's consider another hostage situation in 2005. Akahito Saito, a security guard working in Iraq was killed after being taken hostage, but he was portrayed as a hero by most of Japanese media. So, what's the difference between Saito and those aid workers?

KELTS: I would say the difference is being official. I mean in Japanese society even today having a business card that identifies you as a member of a company, you know, going up to the 5th floor every day and having a role to play is very, very important.

BROOKE: And the aid workers didn't have official standing?

KELTS: Well, this goes into deeper cultural tropes, but there isn't a real history of volunteerism in Japan. Japan still to some extent has vestiges of its feudal past, whereby people lived in small villages and were expected to help one another. The idea of a stranger going into a situation and offering to volunteer, is still quite alien. After the earthquake and tsunami in 2011 volunteers had a very difficult time, especially at the beginning, trying to help out Japanese who thought, “Why are these strangers coming here? What are they doing?” So, those kids, their position was very vague and seen as irresponsible. And I think think this particular situation, this is the difference between how most japanese view Goto, who is a professional journalist, they may have seen him on television, reporting, and Yukawa, who is seen as somebody whose life fell apart, so he ran off to Syria, and now he's in trouble.

BROOKE: And this situation is coming at a complicated moment for Japan--the prime minister Abe is working to increase Japan's involvement with world affairs, and Abe's cabinet recently issued a decision to officially reinterpret the constitution to allow Japan to engage in war if its allies are attacked, among other things.

KELTS: It's very very troubling. The video was released just a few days after Abe declared in Israel that Japan would offer exactly 200 million dollars to support Syrian refugees. The Abe administration is pushing for this greater engagement with the rest of the world, and here what happens? He makes the first big gesture, and a few days later Japanese are watching their own threatened by a knife-wielding terrorist. Depending on how this plays out, the majority of Japanese may feel like Abe's push to rejigger the constitution in Japan's presence is a disaster, that the country should cling to its pacifist ways and get out of war zones.

BROOKE: The novelist Murakami is in that camp, right?

KELTS: Well, Haruki Murakami is what we would call a baby boomer, he was born in 1949. He grew up in a Japan that rapidly developed, that acquired economic status, acquired comfort, wealth. And for someone like Haruki Murakami and his generation, that all happened under the umbrella of pacifism. Why would a nation that has prospered and thrived, you know 70 some years after the war, suddenly make a change? So there's a great deal of anxiety over what Abe was trying to do and now, with this current situation, agony over what Japan should do going forward.

BROOKE: Are there any loud voices saying "We should just pay the ransom, we should just pay and be done with it"?

KELTS: I've asked a number of people in the Japanese media who've said it's just the opposite. That Japan should not pay, partly because a lot of Japanese feel like the country would be shamed if they caved in. In other words, it would be viewed by the rest of the world as a shameful act.

BROOKE: Roland, thank you very much.

KELTS: Thank you.

BROOKE: Roland Kelts is a contributor to the New Yorker magazine. He's also a columnist for the Japan Daily, and he's the author of “Japanamerica.”