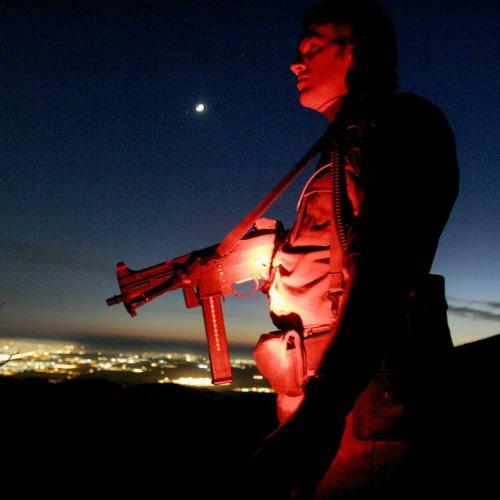

BOB GARFIELD: The murkiness around CBP policies extends far beyond detainment procedure, warrantless device searches or even medieval cavity examinations. It also obscures the use of deadly force at the border. An investigation by The Arizona Republic has found that since 2005, on-duty Border Patrol and Customs and Border Protection agents have killed at least 42 people, at least 13 of whom were American citizens. Some were killed by agents firing across the border into Mexico. But federal investigations into those incidents can take years to be released, and both their processes and their conclusions entirely invisible to the public, even where victims are unarmed teenagers shot from behind. Bob Ortega is one of the journalists behind The Republic’s investigation. Bob, welcome to On the Media.

BOB ORTEGA: Thanks, very glad to be with you.

BOB GARFIELD: Your series describes a number of extremely disturbing incidents, but I want to focus on one in the fall of 2012. It involved a kid in Nogales, shot to death by a border agent.

BOB ORTEGA: Jose Antonio Elena Rodriguez was shot to death, and according to his family, he was merely walking to visit his brother, who was working at a convenience store that’s right next to the border fence. According to agents, there were some people throwing rocks at them just before they fired. A Border Patrol agent, at least one, maybe two, began to fire through the fence and hit this boy ten times in the back and in the head, killing him on the spot.

BOB GARFIELD: Clearly, a troubling incident. And you approached the Border Patrol and you said who was the officer, what is the state of the case, has there been a criminal investigation, and what were you told?

BOB ORTEGA: Well, nothing. The Border Patrol and Customs Border Protection have a policy that they do not release the names of agents. They do not release any details whatsoever about any actions that they may or may not take internally. And, by the way, even their own policies on use of force are secret; they will not release those to the public. Most law enforcement bodies do.

What they’ve said in this, and in many other cases that we’ve investigated, is that they can’t say anything because it's being investigated by the FBI. And so, they defer, ostensibly, to the FBI, although, in fact, they do conduct their own parallel investigations, and they don't release any of that information, at all, ever.

BOB GARFIELD: You filed well over 100 FOIA requests.

BOB ORTEGA: Yes, that’s right.

BOB GARFIELD: What came back from those?

BOB ORTEGA: A lot of them we’re still fighting, In one of them, we wound up getting 12,000 pages of use of incident reports from Customs and Border Protection and then also hundreds of pages of incidents in which firearms were used, and a lot of the information was redacted, but often we were able to piece together information, using a combination of what we found in those files with information that we got separately from the FBI, with public records that we requested from state and local law enforcement officials. We also did a lot of on-the-ground reporting.

But it was very interesting because, if you look at the patterns, the vast majority of the time Border Patrol agents don't use deadly force. They’re able to deal with situations by using less lethal weapons, like they have these things that look like paintball guns that fire pepper balls. In every one of the incidents that we tracked in which an agent shot someone, they reacted with firearms in circumstances that were practically identical to those that many, many more agents reacted to without using deadly force.

BOB GARFIELD: Now, when you say a lot of the documents were redacted, how redacted? I mean, are we talking about FOIA being the new black?

BOB ORTEGA: Yeah [LAUGHS], well a lot of the redactions were bogus. There are certain specific exemptions in FOIA law that are perfectly understandable. If you have an ongoing investigation, for example, you’re allowed to redact information that could interfere with the course of that investigation. You’re allowed to redact information that would violate an individual’s privacy. But if you’re asking for something like what an agent was doing while he’s performing his official function, I don’t think that’s prot3cted by privacy.

BOB GARFIELD: The claims to privacy and security, on behalf of its agents might hold a little bit more water, if the Department of Homeland Security and the CBP didn't have a deal with National Geographic Channel [LAUGHS] for a, a reality TV show called, Border Wars, which shows the Border Patrol in action.

BOB ORTEGA: Exactly. And the thing that’s ironic about this is that when we talk to CBP, they maintain that they don't release the names of agents because if they’re identified by the Mexican cartels, they could be in danger. And yet, every week on this program, there’s faces of the agents, the names of the agents, where they work, what they're doing.

My perception is that it's because they see that as a useful recruiting tool and that the issue has really very little to do with the privacy and, and more to do with whether the agency is able to control the message that is being put out.

BOB GARFIELD: And we’re not just talking about guys with beige uniforms and 9-millimeters strapped to them. We’re talking about the public information officers who give you what answers you get. They won’t even be quoted by name?

BOB ORTEGA: That’s right. They’ll give us a single statement, attributed just to CBP. They’re seeking anonymity for everything that they say and do. If you’re a spokesman, you should be willing to identify yourself. Right after our series ran, I had a conversation with a retired Border Patrol sector chief. You know, he didn’t like everything about the story because he didn’t think it as particularly friendly to the Border Patrol. But he did say, if you look at what we do, we, meaning the Border Patrol, we, on behalf of the American people, are given authority to wield deadly force, under certain circumstances. And yet, the government turns around and says to the American people, we’re not gonna tell you under what circumstances. And he said, that, that – that’s absurd, on its face. This is a former Border Patrol sector chief.

The use of force policy of Customs and Border Protection used to be public. It only stopped being public in 2004, once they were part of the Department of Homeland Security.

BOB GARFIELD: The Office of the Inspector General for the Department of Homeland Security is supposed to be the internal watchdog of the conduct of the agency and its employees. That's what they’re there for.

BOB ORTEGA: That’s right.

BOB GARFIELD: Their findings were kind of jaw-dropping.

BOB ORTEGA: In one part of the report, the OIG Report, the inspector said many agents really don't know, as well as they should, when to use or not to use deadly force. What was ironic about it though, to me, was that all the recommendations for improvements or change were redacted. In fact, we spoke with several members of our congressional delegation after it came out, to see if perhaps they had been able to take a look at an unredacted version, and even they were only given redacted versions of the report. And these are the guys who asked for the investigation, in the first place.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]-

BOB GARFIELD: Bob, thank you very much.

BOB ORTEGA: Thank you.

BOB GARFIELD: Bob Ortega is an investigative reporter at The Arizona Republic.