How Not to Report on a Presidential Election

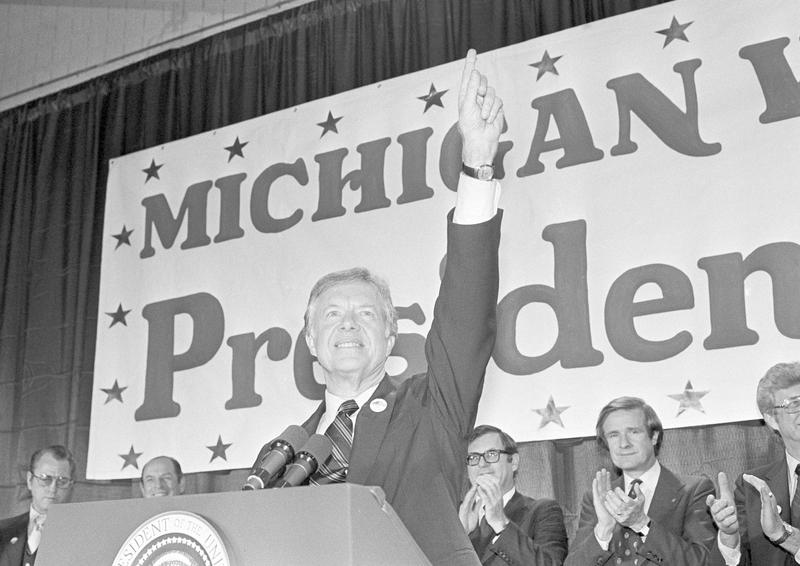

( Jim Wilson / AP Photo )

Brooke Gladstone This is On the Media. I'm Brooke Gladstone, and I'm here with my co-host this week, James Fallows, to chew over some of what we just heard and to take in some of what he's observed about political reporting, from his days on the Carter campaign and in the Carter White House as a speechwriter, and in his own coverage of pretty much every presidential campaign since.

First, just before Trump was elected, you and your wife Deborah Fallows traveled the country, Jim, seriously and extensively to take the nation's pulse and produced the book, Our Towns: A 100,000-Mile Journey Into the Heart of America, and later a documentary. You were heartened by what you found. Let's talk about what Jeff Sharlet laid out. I think he makes a solid case, but I think I'm of a darker disposition.

James Fallows: I think that what he says is true and also there were other things that are true. The task for us is to balance the dark themes that Jeff Sharlet is so astutely writing about, and the other buffering or offsetting themes in American life.

Brooke Gladstone: Can you give a couple of examples of those?

James Fallows: Yes. I grew up in a town of Redlands, California, that went for Barry Goldwater in 1964 when I was a kid. Very conservative in its political leanings, and all of my conscious life has been among people who had a different cultural and political outlook from the one I've come to have in adult life. My wife Deb and I have spent the last 10 years seeing parts of America that don't normally get national media coming to them unless there's an election or a tornado or something of that sort.

We've been aware, I think, of the contradictory realities that people who we know have entirely opposite views to ours politically, and might well be subjects of Jeff Sharlet's book, simultaneously are doing things in their communities to welcome immigrants, to provide for the public schools, to work towards a sustainable future. Jeff Sharlet has found people whose primary identity is their political affiliation. Those people exist.

Brooke Gladstone: Studies suggest that those people are in the majority, that it has surpassed religion and gender, and even race, for being the chief way one identifies oneself.

James Fallows: Who am I to quarrel with data-based science? My lifetimes of experience and my 10 years of past reportorial experience going around the country, suggest that's not how most people actually think. Most people, if you go in and you start out asking them, what do you think about Hillary Clinton? What do you think about Barack Obama? What do you think about Donald Trump? You'll get an answer just like on a cable news show, but if you open-endedly ask them about their lives, their hopes, their fears, their communities, their children, politics will be a part, but not the signal part.

Brooke Gladstone: A lot of your reporting on the book that you did traveling all around the country was prior to the most recent change in our political culture. It may have been heading in that direction, but it didn't achieve the brazenness of its celebration of violence in certain quarters that it has now.

James Fallows: Our understanding of the Trump movement and what I've just been saying about the fact that most people are not mostly animated by political extremism or political resentment, I think was number one, the contingency of the circumstances that brought Donald Trump to office. It was a number of circumstances involving James Comey and countless other dominoes that fell in direction that brought him to office. Of course, he lost the popular vote by a couple of million.

The election day of 2000, when George W. Bush was declared the winner over Al Gore, as of that time, no living American had ever experienced an election in which the popular vote winner did not also take office. It was contingent that Donald Trump took office. Most of the political results since then have suggested a buffering effect. The fact that Joe Biden won by a larger popular vote margin than Hillary Clinton did, the success of midterms after that. America is full of anti-democratic sentiments. It is full of people who seethe with resentment, but metaphorically as opposed to statistically.

Brooke Gladstone: We're so used to hearing that everything about this era is unprecedented in a break from historical norms. The fact that we're even talking about another civil war underscores how different this moment is from say, a Dukakis/George H. W. Bush contest, or Obama against Mitt Romney. You, Jim, see deeply etched patterns carved out by the political press in accordance with the expectation of the audience, which is all of us. You liken that expectation to our need to hear a minor chord resolve.

James Fallows: There are certain expectations we have built-in in narrative and in our personal lives, and in performances.

News clip: If you take the simple scale, the next to last note, the seventh, that's a definition of an interval that is screaming to do that. No matter what chord you put it with, you can't get rid of that feeling like it's going to do that, it's going to do that.

James Fallows: When it comes to media treatment of political campaigns, it's not that these expectations or instincts are wrong or damaging, but it's worth thinking about these grooves in our collective brain, and the ways we as the media, we as the public, are accustomed to think about presidential politics.

Brooke Gladstone: Let's start with the election trope of the new savior. There's such a hunger for a person who will lift America out of its doldrums. As every cycle begins, you can feel the press aching to fall in love, right?

James Fallows: An example from my dim childhood when John F. Kennedy ran for president, a book that changed political narrative lastingly, was Theodore White's The Making of the President 1960, about the Kennedy campaign, and all the things about the glamor of the Kennedys, just the physical beauty of John and Jacqueline Kennedy, his war heroism, which has also been part of a constructed narrative. There was a sense after the Eisenhower era, Eisenhower, a very effective president in retrospect, but less flashy, as we knew, to have this young candidate who explicitly spoke about a new generation of new people.

Brooke Gladstone: A new frontier.

John F. Kennedy: The new frontier is not a set of promises. It sums up not what I intend to offer to the American people, but what I intend to ask of them.

James Fallows: That was an early illustration of the [unintelligible 00:38:10] but periodically, since then, whenever there's been a time of national strain, you can feel a lane opening for whoever's going to be the candidate who says, "I'm the one you're looking for." Not that long in historical terms after Kennedy's race, was the one I worked in in 1976 for Jimmy Carter.

Although it's not generally remembered now, the Carter of those times had a real magic/savior quality to him. It was after Richard Nixon and Spiro Agnew had resigned. It was not that long after the final collapse of Saigon. It was an extremely troubled time for the US and Carter [unintelligible 00:38:48] saying, "I'm not going to lie to you."

Carter: I'll never tell a lie, I'll never make a misleading statement.

James Fallows: I like rock and roll music. I'm young, I'm progressive, I'm a naval veteran. I'm going to redeem what you think about America, and you can skip ahead to Barack Obama who also had that quality in ways I don't need to belabor. In between them, I will submit that Ronald Reagan offered this appeal to people who were on his side politically.

Brooke Gladstone: Directly connected to the new savior trope is this promise to get back to what America really is like. That how we are now isn't really who we are, and this is an eternal theme.

James Fallows: One of the most reliable markers of any presidential campaign is when the candidate, he or she, begins promising to restore real America to real Americans

Speaker 17: In every branch, at every level, national, state, and local, must be as a city upon a hill.

James Fallows: That America is not a country with all the sins and flaws any American historian would dwell upon, but rather it is this city on a hill which needs to return to its city on the hill basis.

Jimmy Carter: I've spoken of the shining city all my political life, but in my mind it was a tall, proud city and teeming with people of all kinds, living in harmony and peace.

James Fallows: When Jimmy Carter was running for president, I was working for him on the campaign in the White House. One of his trademark lines, which originally came out of some impromptu speech, was that America needed a government as good as its people. That's what we've had, most of our history, we've had governments as good as our people, and that's the problem. Carter was using it in a self-flattering way for America that actually we are good and we just need a government that reflect this real us. None other than Mike Pence has begun using that same line.

Mike Pence: The American people are good and decent and compassionate and generous and caring of their neighbors, and I think we just got to have a government as good as our people again.

James Fallows: This was something that Barack Obama, with his particular coding as the first non-white serious candidate for the presidency made as part of his debut in 2004 saying--

Barack Obama: There is not a liberal America and a conservative America. There is the United States of America.

James Fallows: This brings up all the more oddity of Donald Trump essentially lumping the United States right now into the [beep] whole country category.

Brooke Gladstone: Recalling Jeff Sharlet. He said that he made hate patriotic, a kind of love.

James Fallows: There has always been a theme in American life of appealing to certain subsets of America saying that you are the real Americans, you Protestants, you white people, you men, you southerners, you, whatever the category is, you are the real Americans. These other people are the phonies, the intruders. That has been an ongoing theme of those candidates who choose intentionally to rise by bringing out the worst in the American character. Trump has done this, George Wallace did it back in the 1960s and in 1972, Strom Thurmond, when he actually got electoral votes against Harry Truman and Tom Dewey in 1948. It's been there for a long time.

Brooke Gladstone: Another trusted trope in the political reporters quiver, the forgotten voters. Here's a new group we've just identified that will really determine the outcome. Does that trope originate though with the press or with the politicians? I mean, Nixon and Agnew had the silent majority.

James Fallows: It originates from both of them in different sequences. If you look back at winning campaigns, you have the postmortems. I know this firsthand from the Carter campaign, it was there identifying early on what other people had not seen. For example, the Carter campaign, they figured out the Iowa caucuses, whose passing we mourn, they figured out before anybody else and knew how to concentrate there. Richard Nixon famously in 1968 had his southern strategy to realize that the old South was going to become the Republicans base as opposed to the Democrats base because of civil rights legislations.

Brooke Gladstone: You believe in the forgotten voter trope.

James Fallows: I believe there's an ever-changing logic of how you get elected. It's partly luck, it's partly timing, but it's partly knowledge too and science of where you can make your pitch, and it will pay off, where the electoral votes are. I think for reporters, this usually shows up after the election analysis saying after 2016, "Oh, yes, it was these guys in a diner in Kentucky who allegedly were making the difference." We know now that actually that wasn't the case, but there was two years worth of analysis by reporters who visited diners.

A very interesting case of what I'm talking about is the 2022 midterms. It was obvious to practitioners, including many of those doing referendum races in various states, that the decisive issue in that campaign was actually the Dobbs ruling. The effect that the end of Roe v. Wade had on many voters, and especially on female voters, who are the majority. Much of the professional press was saying even the day before the election, that it was going to be about inflation and gas prices and the withdrawal from Afghanistan. That's why most of the press seemed to be taken by surprise by all of this.

The meta point I'm making is that probably the press should put less emphasis on prediction of any kind just because we are all so bad at it. If there's less prediction, what becomes what you do more of? I think it is the challenge of trying to say, where are we in terms of the ways the country has changed in the past 10 years, the way it is likely to change in the next 10 years?

You can say that with more confidence than you can the outcome of an election, and what are the levers that a government has and doesn't have over all these factors? I know what you're thinking, but are too polite to say right now, Brooke, which is, that sounds boring, but the trick of writing about everything else in life is that reporters specialize in making things that could be boring interesting. If it were more like the best parts of the rest of our journalism, including not being boring, that's what I'm looking for.

Brooke Gladstone: The last trope I'm going to talk about, one that I believe, but I think you'll probably have an argument against, it's a hardy perennial, and it is that this is the most important election ever.

James Fallows: On the one hand, certain elections really, really have mattered in American life. The election of 1860 with Abraham Lincoln, the most important in my view, 1932 with Franklin Roosevelt, very important, Barack Obama in 2008, the electoral college victory of Donald Trump. Those were all real turning points in American life. Things would've been different in all those cases if the result had gone the other way.

Yes, there are elections that really make a difference. I think that it does become a crutch both for politicians and for reporters to use this line. For politicians because you want to get out the vote. For reporters because it's part of the standard toolkit we bring out. It's like a macro key you would have. It's both true and familiar.

Brooke Gladstone: I notice how much history you yourself have covered or lived through that you used to bolster your discussion of these election tropes.

James Fallows: It is true that I have lived through a lot of American history firsthand. I'm of the dreaded boomer era. My emphasis on tropes is partly because I think there are a few ongoing themes in American life that are always there. One of them is, "America is in trouble and always has been." The question in any given moment in American life is how does the quotient and the forces leading to trouble match the forces that are resisting that trouble?

Brooke Gladstone: It isn't just a trope, it's a truth.

James Fallows: It is a truth, and I will contend, if you name almost any year in American life, I can reel off for you the tragedy that was happening at that time, the cruelty, the people who were being oppressed, whose hopes were squashed. You can also think of the people who were pushing the other way. There was the original Gilded Age, which is so much like our current moment in the late 1800s. There was the populist and progressive movement after that in the early 1900s. The question is whether we'll have anything like that populist and progressive movement ourselves.

I fully recognize the idea that there are tremendously destructive and hateful forces that are threatening our public life right now. I also recognize in the 1920s, The Ku Klux Klan was entering a new heyday and the lynchings were widespread across the Midwest and the South then.

Brooke Gladstone: There was a plague in the Middle Ages that killed a third of the world. Do we really have to harken back to disasters that are even worse than the one we are now in?

James Fallows: We don't have to hark back, but it is worth recognizing that we are in trouble and we have always been in trouble. The duty has always been to deal with that trouble because it's always been there. When I was in college in 1968, the person who was likely to become president, Robert F. Kennedy was assassinated. Within almost a month's time, Martin Luther King, the leading civil figure of the mid-20th century was assassinated, and there were just riots every place.

The point is not, "Oh, I've seen it all. You kids these days stop your whining." The point is, this is our national story. Our national story is never resolved, unlike a chord, our national story all requires a force of progress against the destruction, always requires some idealism against the venality. It requires leaders who are pushing up rather than punching down. That is our ongoing predicament. Yes, we pay attention to the people who are threatening us now, and we see ourselves in continuity with those who did it before and those who will have to do it forever.

Brooke Gladstone: You don't give way to existential threat.

James Fallows: Life in my personal and political view is ongoing effort and an ongoing struggle. You're never coasting. It is a life of permanent engagement. I think people in the press should welcome that as part of the mission to which we can contribute.

Brooke Gladstone: Thank you so much, Jim. It's been wonderful having you with us this week.

James Fallows: Brooke, it is a real pleasure and honor to be part of your little team here.

Brooke Gladstone: James Fallows writes the newsletter, Breaking the News on Substack, which I can attest is definitely worth a read.

[music]

Brooke Gladstone: On the Media is produced by Micah Loewinger, Eloise Blondiau, Molly Schwartz, Rebecca Clark-Callender, Candice Wang, and Suzanne Gaber. With help from Shaan Merchant. Our technical director is Jennifer Munson. Our engineer this week was Josh Hahn. Katya Rogers is our executive producer. On the Media is a production of WNYC Studios. I'm Brooke Gladstone.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.