A History of Miracles and Mistakes

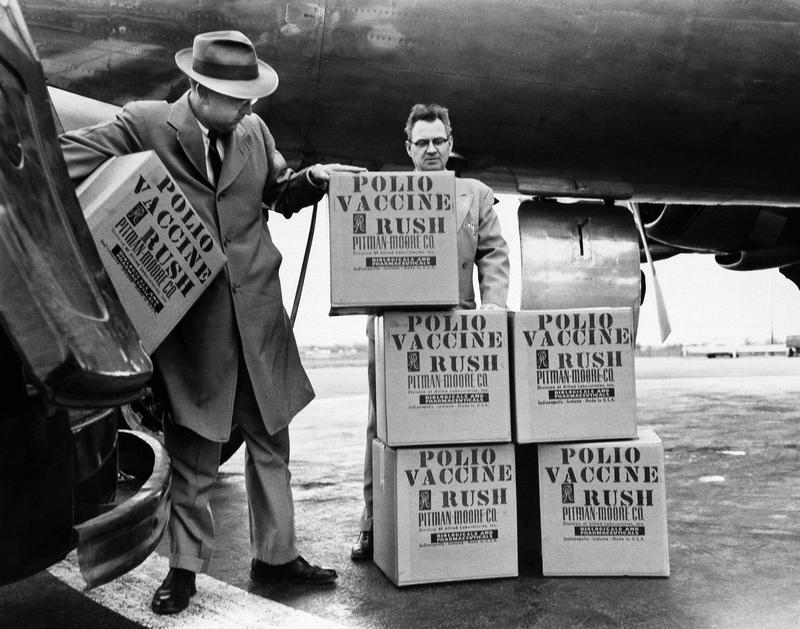

( Anonymous / AP Images )

BROOKE GLADSTONE This is On the Media, I'm Brooke Gladstone. This pandemic has offered a vivid case study of science supercharged. It's not the first such case, though, and the course of medical progress never did run smooth. Every advance or treatment carries some degree of risk.

PAUL OFFIT Everything at some level is a gamble. And I think we don't like to think of it that way. But there really are never safe choices because there's always some risk.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Dr. Paul Offit was a co-inventor of the rotavirus, a treatment for a severe infection threatening infants and young children, and even as his own vaccine cleared a phase three trial with 70,000 kids and was deemed safe to go into the arms of kids, there wasn't closure.

PAUL OFFIT But even then, you don't breathe a sigh of relief because 70,000 children isn't 70 million children and you're always worried that you're going to find something out afterwards that you wish you'd known before.

BROOKE GLADSTONE But the public, he reasoned, isn't aware of how that feeling informs science. His solution illuminates some of the times things really went sideways. Dr. Offit is the author of the new book You Bet Your Life: From Blood Transfusions to Mass Vaccination, The Long and Risky History of Medical Innovation, where he relates the tragic mistakes behind the miracles of modern science like organ transplants, anesthesia, antibiotics, X-rays, gene therapy and, of course, vaccines. His book featured a story that's been sometimes invoked during the rush for a COVID vaccine. When Jonas Salk declared his polio vaccine safe, potent and effective, five companies rushed in to mass produce it, and one of them cut corners in the filtration and purification process. The year was 1955.

PAUL OFFIT They failed to do what Salk had done, which is to take polio virus and completely inactivate it with a chemical, and as a consequence of 120,000 children were inoculated with live, fully virulent polio virus. 40,000 of those children developed abortive or short lived polio, meaning temporary paralysis. 164 were permanently paralyzed for the rest of their lives and 10 were killed. I think that was probably the worst biological disaster in this country's history.

BROOKE GLADSTONE It became known as the Cutter incident after the California based lab Cutter Laboratories. In the book, you described it as a problem of scaling up, right?

PAUL OFFIT So, when Salk made his vaccine, he took the virus, grew it in monkey kidney cells and then purified the virus away from those cells so that it was pure virus. And then he inactivated it with a chemical and he used a very slow filtration system. It produced a product that was called gin pure, meaning it was just perfectly clear. When it went to scale up, that was considered too slow, so they used a different kind of filtration system, which wasn't as efficient. These polio virus particles would get sort of trapped in this cellular debris, and so the formaldehyde, the chemical used to inactivate the virus, couldn't penetrate that cell debris. And as a consequence, there was live virus in that vaccine. It was really a tragedy of epic proportions.

BROOKE GLADSTONE What should we learn from the run up to a safe and effective polio vaccine?

PAUL OFFIT There's always a human price to be paid for knowledge. Even if you look at the polio vaccine trial. Jonas Salk didn't want to do a trial of his vaccine. He felt he had tested it in 700 children in the Pittsburgh area, he told his wife, Donna, 'Eureka, I've got it.' And he didn't want to inoculate children with a placebo, knowing that every year, 20,000-30,000 children would be paralyzed by polio and that 1500 would die. But nonetheless, the March of Dimes who ran this program insisted on it. And so that was the trial. 420,000 children were inoculated with Jonas Salk's polio vaccine, 200,000 children received placebo, and when it was over, the person who headed the trial, Thomas Francis, stood up at the podium at Rackham Hall at the University of Michigan and said those three famous words: safe, potent and effective. Those three words appeared on the headline of every newspaper in this country. Church bells rang out.

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT an historic victory over a dread disease that dramatically unfolded at the University of Michigan. Here, scientist usher in a new medical age with the monumental reports that prove the Salk vaccine against crippling polio to be... [END CLIP]

PAUL OFFIT So how did he know it was effective? He knew that vaccine was effective because 16 children died from polio in that study, all in the placebo group. He knew it was effective because 36 children were paralyzed in that study, 34 in the placebo group paralyzed for the rest of their life. I mean, those were first and second graders in the 1950s. I was the first and second grader in the 1950s. But for the flip of a coin, those children could have lived a long fulfilling lives. And I think that's the story that often gets lost here. I mean, for example, I'm on the FDA's vaccine advisory committee. When we approved Pfizer's vaccine for 12 to 15 year olds. That was a 2300 child study. After that was approved, I got a lot of pretty angry e-mails from parents saying, 2300 children, really? That's all you want to test. You just did a forty thousand person trial with Pfizer's vaccine in adults. You did a thirty thousand person trial of adults for Moderna's vaccine, and now you're going to test only 2300 children before it's going to be given to millions of children. Is that what you want to do?

BROOKE GLADSTONE And what do you say to those parents?

PAUL OFFIT What I say is I say the issue is never when you know everything. The question is, when do you think you know enough? And we could have done a twenty three thousand child study for the 12 to 15 year old, in which case then there wouldn't have been 18 cases of COVID in the placebo group, as was true in the twenty three hundred trial, there would have been a hundred and eighty children who suffered COVID in the placebo group, some of whom would have suffered it severely. When do you know enough knowing that you might be wrong knowing that when you're making a decision based on thousands of children for a vaccine that's not going to be given to millions or tens of millions or hundreds of millions of children throughout the world? Do you know enough? And I guess the purpose of writing this book was to make people aware of the fact that they should have a more reasonable understanding of how this process works so that they don't have expectations that are unrealistic.

BROOKE GLADSTONE What do you think's off kilter here?

PAUL OFFIT I think if you ask people, Do you think we're going to know more about science, more about medicine 100 years from now than we know now? I think everybody would say yes, but when it comes to an issue that they're dealing with now, they want to believe, you know, everything and you don't. So, for example, look at these vaccines that are now used to prevent COVID. We were surprised by the fact that the mRNA vaccines caused myocarditis. Inflammation of the heart muscle. It was rare, maybe one in 20000 people, all in all, but real. We were surprised that the Johnson Johnson vaccine was a very rare cause of clotting, including severe clotting in the brain. Rare, roughly 1 in 500000, but real. Those were surprises. People are always disappointed by that, but would they-- should take the heart, is that one there's systems in place to pick that up. And two, that this is always true. That knowledge always comes with a human price. Always.

BROOKE GLADSTONE How did you feel about warp speed, the fact that it was called warp speed and that this was an unprecedented effort? Nothing like this has ever happened before.

PAUL OFFIT It was remarkable. I mean, we identified the SARS-CoV-2 virus and sequenced it in January of 2020. Eleven months later, we had done two large clinical trials, the Pfizer trial and the Moderna trial with a technology, messenger RNA, that had never been used before. And the vaccines were found to be remarkably safe and remarkably effective. But I think the terminology that surrounded that created the sense that timelines were being skipped or truncated or worse, that vaccine safety guidelines were being ignored. But that really wasn't true. The size of those trials was the size of any typical pediatric or adult vaccine trial. I think the difference was length of time for efficacy. You only really knew it was effective for a few months. You didn't know beyond that. On the other hand, you're not going to do a two or three or four year study to see just how long efficacy lasts in the midst of a pandemic.

BROOKE GLADSTONE You observed, though, that the Cutter incident came back in the news because warp speed did to an extent mimic the 1955 polio vaccine program.

PAUL OFFIT That's right. You were mass producing at the same time that you were doing the studies. Normally, companies don't do it that way. They go sort of phase one trials then phase two trials. Then you do the phase three trials where people get the vaccine or they don't get the vaccine. And if it works, then you mass produce it. These vaccines were being mass produced before you even knew whether they work before you even knew whether they were safe, which is really what happened with the polio vaccine trial. I mean, the length of time that it took to essentially license the polio vaccines in the mid-1950s was two and a half hours.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Shouldn't we then have been squeamish if we remembered the Cutter incident?

PAUL OFFIT Right. But you know, there are no risk free choices. There are just choices to take different risks. So the question is when you knew that this vaccine was coming out, you knew that it was a novel technology. You knew that it had been developed very quickly. And yeah, I think you should have been a little squeamish. The people who got that vaccine early on, especially in the clinical trials, were brave. So people could reasonably say, Look, I see that, that there's a learning curve here. I'm just going to wait till the learning curve is over. But the learning curve is never really completely over.

BROOKE GLADSTONE I kind of love the analogy you offered that describes the different kinds of risk people face when making medical decisions. It begins by imagining you are walking through the woods, right?

PAUL OFFIT And so then you come upon a bridge, which is, you know, a little rickety. But you know, many people have crossed it before, so you're willing to take that risk because everything is a risk. I mean, aspirins are a risk, antibiotics are a risk. Those are the sort of the normal risks. The analogy that I try and make here is that you see things differently if you're being chased by a tiger. You know you're much more willing to take the rickety bridge. Those are the first heart transplants, the first kidney transplants. I think the last 24 hours there was a kidney transplant using a pig kidney. You know, you have 4,000 people currently on the heart transplant waiting list. 1300 of them will die while waiting. You don't know whether you're one of those 1300, so you could say, You know what? Let me try getting a pig heart. Be one of the first to do that. That may solve my problem completely.

BROOKE GLADSTONE As you detailed in your book, there was an effort to transplant animal parts in the past and it never worked,

PAUL OFFIT Especially for blood transfusions. I mean, you know, blood transfusions were done in the 1600s and they were done using barnyard animals as a source of blood. For some people, the blood transfusion actually worked fairly well, although they always suffered transfusion reactions, meaning fever, darkened urine. OK, so now you're in the early 1900s, you figured out blood typing. A, B, O typing. Would you get a blood transfusion now? OK, but remember, you haven't yet figured out the RH typing that so-called if you're O positive. OK, now you're in the 1940s, would you get a blood transfusion now, knowing the hepatitis B virus is now in the blood supply and has been at one point just one of the largest single source fatal outbreaks among the American military. OK, so now you're in the 1970s, you can test for hepatitis B virus. Would you get a blood transfusion now? And what comes into the country – AIDS. The blood supply gets contaminated with human immunodeficiency virus. Okay, we can get a blood transfusion now that we figured out that HIV is in the blood supply and can test for it. And would you get a blood transfusion now, knowing that there are viruses we don't test for, knowing there are viruses we don't know about? There's always some level of risk.

BROOKE GLADSTONE In his New York Times review of You Bet Your Life, Cass Sunstein wrote that in life and in public policy, many people in Europe and the U.S. are drawn to the precautionary principle. Whenever an innovation threatens to cause harm, we should be exceedingly cautious before we allow it. Offit's examples in the history of medical advances demonstrate that in its most extreme forms, the precautionary principle is self-defeating.

PAUL OFFIT The general point is you have to keep trying and don't let a setback make it so that you simply stop pushing forward. So probably the best example for me, because I lived through it, because I'm at the University of Pennsylvania was Jesse Gelsinger. So Jesse Gelsinger was a 19 year old man who lacked a certain liver enzyme that helped him convert food and energy, which meant he was taking 30 pills a day and that he had a restrictive diet, which is hard for a –

BROOKE GLADSTONE Teenager.

PAUL OFFIT A teenager. So he was, he was willing to allow himself to be part of a trial where he received the gene therapy, which was a common cold virus called adenovirus that was genetically engineered so that he couldn't reproduce itself and cause disease. And what happened was very soon after he got that, he had an overwhelming kind of sepsis like response, meaning it looked like he had been infected with a bacteria that had overwhelmed him. That actually ended up helping a lot of people down the line when you saw that he had an overproduction of an immune protein called interleukin six. And at the time, there was nothing to have countered that. Now we have a monoclonal antibody called tocilizumab, which can counter that. Would that really put a chill in gene therapy research? It really set it back a solid 20 years, and I think we should have just learned from that and move forward. Instead, you know, we put all these kinds of federal regulations to make sure it didn't happen again, but of course, it was going to happen again. I mean, you can't really legislate out these kinds of unfortunate problems because as you move forward into new territory, you're always going to be surprised by some of the things that you find.

BROOKE GLADSTONE What was kind of chilling about what happened to Jesse Gelsinger decades ago was that he experienced a cytokine storm, a phrase we learned during COVID. His immune system overreacted. Many people in the early stages of COVID died precisely for that reason.

PAUL OFFIT That's right. And now we know that dexamethasone, which is a steroid that inhibits your ability to develop a vigorous immune response, is helpful. You would think it would be counterintuitive to give something to suppress your immune system during an infection. But that was exactly the right thing to do. But again, we learned as we went.

BROOKE GLADSTONE What are the things that the public ought to keep in mind, then, when taking in coverage of a new medicine or procedure or breakthrough?

PAUL OFFIT I think you should get all the information you can. So on October 26, the FDA's Vaccine Advisory Committee will meet to discuss vaccines for the 5 to 11 year olds. They'll probably be about several thousand children who will have gotten this vaccine, and we'll have data on what their immune response was. We'll have data on safety. We may well not have data on whether or not it worked. We're going to try and say that, well, if you had this immune response, it's likely to work. Is that enough? Is that enough information? Do we know enough then to go forward and give this vaccine to hundreds of thousands or millions or tens of millions of children, but realize that on the other side, you know, we're seeing 150,000 cases in children a week. We're seeing 2,000 children being hospitalized every week. Children now account for more than a quarter of the cases as this Delta variant has reached down into the susceptible population and is causing them to be more likely to be infected than they were when the virus first came into the United States, at which point they only accounted for three percent of infections. So this is now a childhood disease. When do we know enough, remembering that we never know everything, and so that's always the balance that you have to take. I mean, I think that from the standpoint of a parent, if the FDA has reviewed it, if the CDC has reviewed it and they have come forward with the notion that we think we know enough, I think that's fair because remember, if you choose not to get it, you may be one of those unfortunate parents who have to deal with their child in the hospital or worse.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Finally, why did you title your book You Bet Your Life?

PAUL OFFIT Because at some level, we always are betting our life. I mean, if you look, for example, if this is a story just in the news, in the last couple of weeks. You know, aspirin therapy used to be given for everybody who is at high risk of a stroke or high risk of a heart attack, had high levels of bad cholesterol, had high blood pressure and then they sort of modified that through really, it should just be for those people who've already had a stroke or had a heart attack. Because if you take aspirin, you know you increase your risk of bleeding, including severe bleeding, you know, bleeding between your skull and your brain or bleeding behind your eye, etc. So there are risks to taking aspirin. And now even that's being modified. You're always at some level betting your life. And I guess in part, it's because I'm old enough to remember Groucho Marx.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Thank you very much.

PAUL OFFIT Well, thank you, that was fun.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Dr. Paul Offit is a professor of vaccinology at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania and author of the new book, You Bet Your Life: From Blood Transfusions to Mass Vaccination, The Long and Risky History of Medical Innovation. Coming up: the shape of stories, according to Kurt Vonnegut. This is On the Media.