America's History of Hoaxes and Popular Delusion

( Harvard Theatre Collection, Houghton Library )

[PROMOS]

BOB GARFIELD: This is On the Media. I’m Bob Garfield.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And I’m Brooke Gladstone. To conclude, we end as we began, with the cataloguing and codification of flimflam. According to Kevin Young, author of Bunk: The Rise of Hoaxes, Humbug, Plagiarists, Phonies, Post-Facts and Fake News, the hoax has long been America's way to confront, while still avoiding our conflicts and fears, insecurities and divisions that have plagued us since our birth. Kevin, thanks for doing this.

KEVIN YOUNG: Thank you.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: You wrote that if Victorian England was the Age of Equipoise, then 19th century America was the age of imposture, hypocrisy. What made America more hypocritical than England?

KEVIN YOUNG: Well, I think in regards to the hoax, a lot of it had to do with slavery. In the Penny Press, the place where a lot of these hoaxes circulated, starting in the 1830s, papers had been a nickel and then they were a penny, they needed content and the hoaxes provided a way for people to work out some of these questions of freedom and slavery. But they often weren’t addressing slavery. They often were thinking about freedom as if everyone were free, and they weren't.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So while in the 18th century, England had, you know, Shakespeare fakes, the US had the Moon hoax.

KEVIN YOUNG: Yeah, the Moon hoax is a fascinating hoax. It happened in 1835 when a man named Richard Adams Locke wrote anonymously these stories about seeing life on the Moon.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: How did it speak to beliefs that were rife in the nation?

KEVIN YOUNG: These figures he describes were in a way displacing some of the questions that we were having. The [ ? ] described in ways that black figures are described, ideas like wooly hair and things like that, and there were biped beavers on the Moon. People on Earth had reactions to these figures. One group offered to send bibles to the Moon to Christianize these figures. And what was brilliant about the Moon hoax is it started in a sort of pseudoscientific way. And, of course, race too is a sort of pseudoscientific idea that it gets more and more entrenched as the century goes on.

There was also an idea at the time of how these figures on the Moon actually were signs of order in the universe. I think it's very clear, once you start thinking of it allegorically, that that was one part of its appeal.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: In other words, there were beings that were clearly of a higher order than other beings.

KEVIN YOUNG: Yeah. I think the hoax at this time had people thinking about who belonged and who didn’t. It wasn't simply that they believed all of it but it was a kind of fakery that led to questions, that later PT Barnum would play with, about you too can be an expert, you too get to decide in this new nation who belongs and who doesn't.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Now, that seems to echo our present, doesn't it, the sense that experts can be easily cast aside and everyone can decide what the laws of physics are?

KEVIN YOUNG: [LAUGHS] Yeah, I mean, I very much was thinking about the ways that the Penny Press kind of served a little like the internet --

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm.

KEVIN YOUNG: -- and that the internet itself provides this place where we get to decide, we get to Like, you know, we get to re-post things. One thing though I would say is different is I think the audiences were very sophisticated then, and I almost think that, to their credit, there was this idea that everyone could be an expert, [LAUGHS] which is very different than now where no one is an expert.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: What’s the difference between everybody being an expert and no one being an expert?

KEVIN YOUNG: I think one is this democratic principle that you can argue over. And now, there’s this idea that there are no people who can say for sure what is happening. Barnum used fake doctors to authenticate things. This isn’t that much better but at least there were doctors.

[LAUGHTER]

And now I think that would be to your discredit, to be an expert. To be a scientist talking about climate change, for instance, gives you no more standing than someone who’s like, it doesn’t seem that warm to me today.

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

So, therefore, there is no global warming.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So PT Barnum, what did he represent to the average 19th-century American?

KEVIN YOUNG: The American art of reinvention. He made it big and went bust a number of times. He was a showman in an age of showmen. He really invented that idea. He helped us invent the modern idea of the circus and also the modern idea of the museum. He had a thing called the American Museum, and that’s where a lot of his exhibitions happened. And it wasn’t a museum how we think of, it was more like a kind of Vegas-y show palace all in one, where you could see high art and then you could also see the bearded lady. And I think his brilliance was to make those things the same kind of experience.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Yeah, because Barnum drew a distinction between humbug, which he said was showmanship, and lying, deceit.

KEVIN YOUNG: Yeah, I think for Barnum, humbug required at least a good show. One of my favorite quotes is where he said, “Every crowd has a silver lining.”

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

He very much was interested in the ways that as a group we might be fooled. He’d leave your pockets a little lighter but also, you know, you feeling a little bit fuller. He would show figures like Joyce Heth, which was his first big exhibition and, and hoax, this woman he claimed was George Washington's nursemaid, which would have made her 161 years old. He advertised this very fact, 161 years old, come see her. There were debates in the press over whether she was real at all, was she made of rubber [LAUGHS] or an automaton?

And then we step back and think, well, she was also a black woman that Barnum possibly enslaved. She had been a slave before. And then when she died, Barnum charged admission to her autopsy to see whether or not she was 161, which he well knew she wasn’t.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So there was a dehumanization --

KEVIN YOUNG: Oh yeah.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: -- of, of Joyce Heth. On the other hand, I was reading a lot about her because of your book. You know, it isn’t altogether clear if she was in on it. She did make money. Some say that she actually bought the plantation that she had been once enslaved on. Or this may be part of her myth.

KEVIN YOUNG: Right.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So many stories, some in which he seemed like a horrible monster, in others, he’s his accomplice --

KEVIN YOUNG: Right.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: -- in, in hoaxing the public. And, and you’re left more confused than where you began.

KEVIN YOUNG: That sounds like Barnum.

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

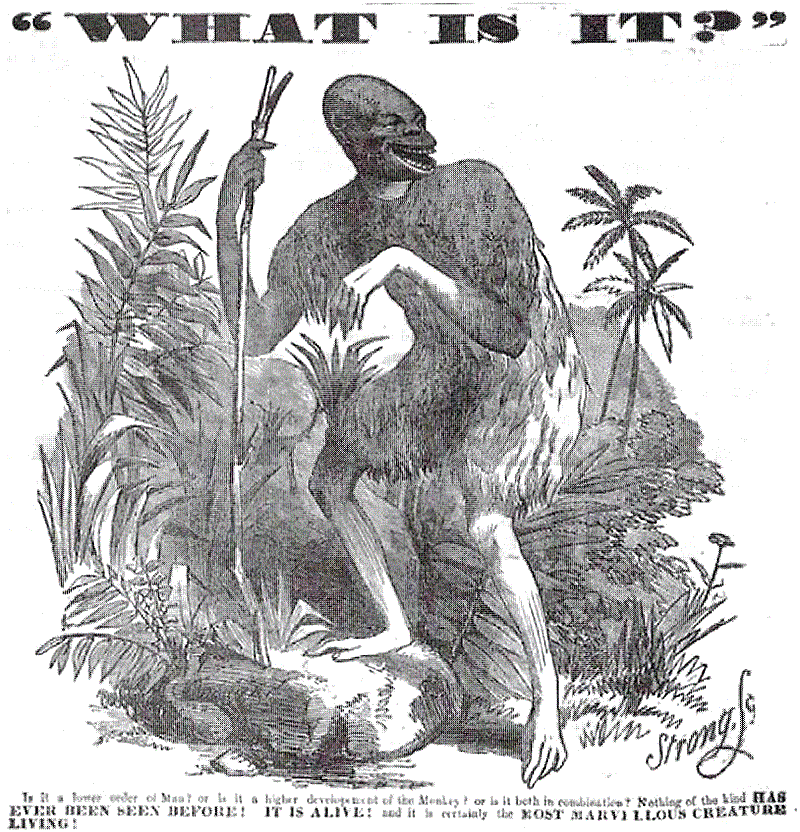

[LAUGHS] One of his other really important exhibitions is in 1860, and it was “What is It?” And that exhibition was of a black man who he asked us to wonder about, whether that person was the missing link. It’s a small thing but in my research I realized that the “It” was capitalized and the “is” was not. On the eve of the Civil War and there you have this black man viewed as an “It.” And that questioning is Barnum's troubling genius.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: These two examples, they’re obviously predicated on racism but Tom Thumb was also a stupendously popular Barnum find. And around the same time, Barnum was showing the “What is It?” exhibit, he was also arguing for the abolition of slavery and suffrage for black men. How do you square these two depictions of Barnum, which seen so at odds with each other?

KEVIN YOUNG: Well, I think it goes back to the contradictions that are part of our founding. Those kind of questions are ones the hoax makes use of, plays with. I started to think about the ways the hoax was almost always about race and then the ways that race itself can be a kind of hoax. People who often were called “freaks” helped us think about that: Who are we? How are we made? You know, we should note, there are people, often white, who pretended to be the other.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm.

KEVIN YOUNG: And that kind of use of blackface, I think, is really important in the book too because it emerges at almost exactly the same time, in the mid-1830s, as the Penny Press, as Barnum, not accidentally. And I trace that tradition of sort of pretending to be what you’re not through time ‘til now. I think there’s a lot of continuity between our time, say, a reality show. We know when we see a reality show it's not totally real.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm.

KEVIN YOUNG: We take pleasure, and at least I do, I like some reality shows a lot. [LAUGHS]

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

But, at the same time, they’re very much playing with some of these deep questions of race, gender. And I think in the case of the hoax more broadly, they also play with questions of life and death and freedom and its opposite.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: You said that there seemed to be something especially American about the hoax and that flimflammery is as American as jazz.

KEVIN YOUNG: Well, the very term “conman” is an American invention.

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

And, [LAUGHS] while I don’t think that America invented the hoax, I think, in many ways, they perfected it.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: You wrote that the hoax and the conspiracy share an equally elaborate dance, the former accusing the world not only of hoaxing but also of covering it up, the hoax, instead, offering advocacy. So can you point to some major hoaxes of our time?

KEVIN YOUNG: I mean, I think birtherism is a big one. It goes right to the heart of origin and Americanness and race. I mean, Rachel Dolezal, I think, is a good one.

[CLIP]:

FEMALE CORRESPONDENT: The civil rights leader accused of faking her black identity is now reacting with defiance against allegations of violating ethics rules. Rachel Dolezal stepped down this week as leader of her NAACP chapter in Spokane, Washington.

KEVIN YOUNG: I tried to understand why couldn’t she just identify in a non-taking over way, like why couldn’t you just say, I’m an ally. That’s one of the problems with that, is it really falls into a long line of blackface.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm.

KEVIN YOUNG: But I also think there’s something more nefarious, which is that they see blackness as a kind of trauma. There’s often not a lot of joy in these hoaxes that plagiarize other people's pain.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Is that what you meant when you said, once the hoax sought to praise, now it mostly traffics in pain?

KEVIN YOUNG: That is what I meant. When someone's pretending to be a gang member from South Central who isn’t, or pretending to be Native, they often are looking at the worst possible notion of the other person.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm.

KEVIN YOUNG: And I, I think that that's really -- it’s connection to Barnum but also a kind of difference.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: It strikes me that this is the dark side of Barnum we’re living in these days, Barnum without the optimism or without the confidence from which we get the phrase, “conman.”

KEVIN YOUNG: I think that’s well put. We’re not even being asked to give our confidence. We’re not even asked to believe some of the lies we’re told [LAUGHS], I think. And I think that's the troubling difference, even, between humbug and the hoax and between the hoax and BS, which doesn't even care if you believe it.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Interesting that you mention reality TV because in order to enjoy that, you have to accept that a lot of what you're watching is cooked, isn’t real.

KEVIN YOUNG: Right.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: If you take a reality show guy and you put him on a podium in real life and people bring that same tolerance for exaggeration and deception and manipulation to that forum, a lie becomes utterly normalized.

KEVIN YOUNG: I worry, and I say this aloud in the book, that we’re headed toward a half-hoax world, one where things are just always a little bit fake. But then there’s really the danger of everything is fake, and also an idea that, well, we can’t ever really know, when I think we can.

The arguing over what should be established facts becomes really strange and infectious. And it’s not an accident that the press is being attacked worse than ever as a very idea when I don’t think that was the case in Barnum's day. And that’s, again, where I think the horror of the hoax has overtaken us.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: If there were a single idea in this half-hoax world that we live in now that you would hope that a reader would take away from Bunk, your book, what would it be?

KEVIN YOUNG: I do think we need to be skeptical but not cynical because, oddly, the cynic is almost more vulnerable to the hoax. I think there’s a quality of overestimation of oneself.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Do you think that Barnum would be a success today?

KEVIN YOUNG: I think I see Barnum a lot today. He had a real nose for what people wanted, even though they didn’t know.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Kevin, thank you very much.

KEVIN YOUNG: Thank you very much.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Kevin Young is the director of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture and author of Bunk: The Rise of Hoaxes, Humbug, Plagiarists, Phonies, Post-Facts and Fake News.

[MUSIC/MUSIC UP & UNDER]

BOB GARFIELD: That’s it for this week’s show. On the Media is produced by Alana Casanova—Burgess, Jesse Brenneman, Micah Loewinger and Leah Feder. We had more help from Monique Laborde, Jon Hanrahan and Sarah Chadwick Gibson. Special thanks to Andy Lanset of WNYC’s Archives Team. And our show was edited -- by Brooke. Our technical director is Jennifer Munson. Our engineers this week were Sam Bair and Terence Bernardo.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Also thanks to Corey Boutilier, our WNYC colleague behind the documentary, P.T. Barnum: The Lost Legend.

Katya Rogers is our executive producer. On the Media is a production of WNYC Studios. I’m Brooke Gladstone.

BOB GARFIELD: And I’m Bob Garfield.

* [FUNDING CREDITS] *