A Historian Reckons With Gaps in the Archives

( Wikimedia Commons / Middleton Place )

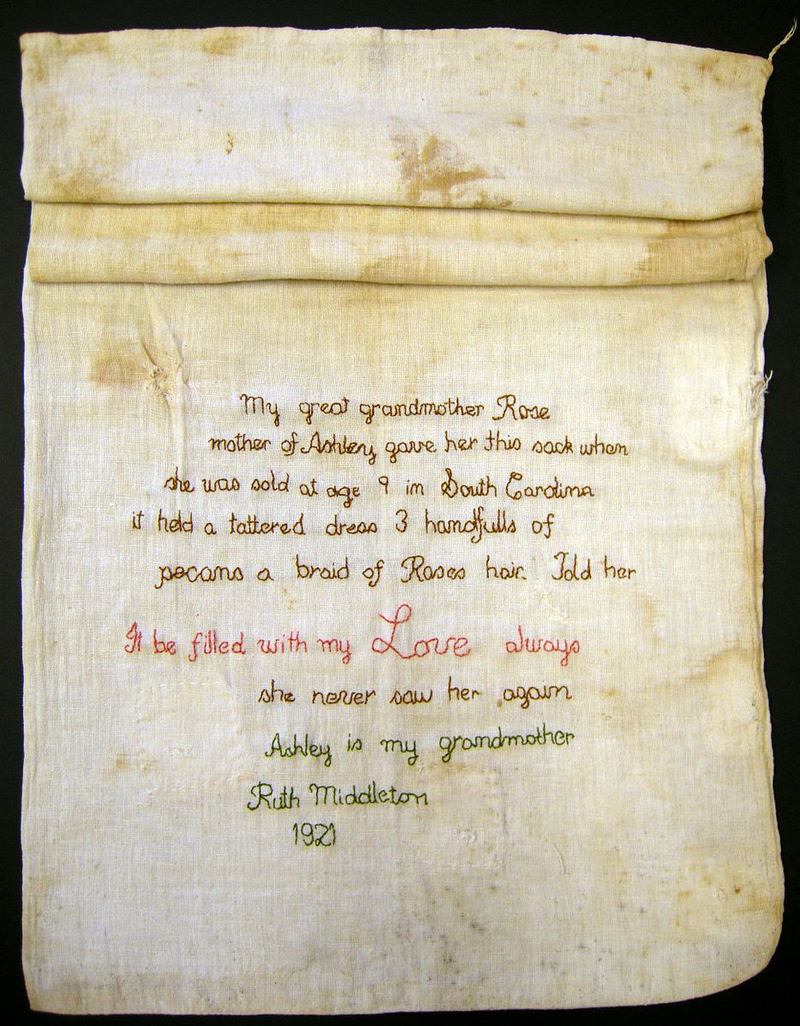

Brooke Gladstone This is On the Media. I'm Brooke Gladstone. We know history is written by the victors and that the gaps in the record mostly relate to the losers or the powerless. About them, there may be little left to find, so you work with scraps and shreds. Or in this case, an enslaved little girl's tattered seed sack rediscovered more than a century after its creation. That's what historian Tiya Miles decided to do when she saw it displayed. Here she reads the embroidered inscription.

Tiya Miles My great grandmother, Rose, mother of Ashley, gave her the sack when she was sold at age nine in South Carolina. It held a tattered dress, three handfuls of pecans, a braid of Rose's hair, told her it be filled with my love always. She never saw her again. Ashley is my grandmother, Ruth Middleton, 1921.

Brooke Gladstone Miles is the Michael Garvey professor of history at Harvard University and Radcliffe Alumni Professor at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study. Two years ago, her book called All That She Carried the Story of Ashley Sack, a Black Family Keepsake, won the National Book Award and ten other prizes. During her research, she learned that when the sack was first displayed, so many viewers cried that the curators handed out tissues beside it. Miles had often come across instruments of torture in her work shackles, neck braces. But this sack opened a window into a profound and universal love emanating still from Ashley's sack.

Tiya Miles I am an academic and I spend a lot of time in my head. But when I saw this artifact, I was completely overcome and overwhelmed. The object itself reflects not only the story of this family and the story of African-American women who were enslaved, but also the critical importance of affection, of care, of kinship ties to enslaved people.

Brooke Gladstone So you looked through slave holding records to find a record of an Ashley and a Rose together in a particular location. And you found that they were likely under the ownership of a man named Robert Martin.

Tiya Miles The more I dug into the materials, the clearer it became that while Rose was a very common name for enslaved women in this place, Ashley was a very, very rare name. Ashley tended to be a name reserved for the English gentry. So if I could find one of these rare Ashley's in the same set of records with a Rose. These were likely to be the daughter and mother pair I was looking for in the right time the right place in the same set of publicly available South Carolina documents.

Brooke Gladstone With regard to Ruth, who embroidered the sack of her grandmother. It was easier to uncover her likely identity because there were more written records. She was married and pregnant. At 16. She moved from the South to Philadelphia around 1920 and eventually became a regular feature in the Black Society Pages.

Tiya Miles Yes, Ruth is a fascinating figure in this history. I mean, she is someone who came from the family of Ruth and Ashley, who had experienced the worst that we can imagine as parents today. And yet Ruth was born free in South Carolina and decided to change her life, moved to the north, as many African-Americans were doing in this first wave of the Great Migration. And in Philadelphia, she became a young mother. And it was around this time that she had her first child, the girl named Dorothy, that Ruth Middleton started stitching this story of her foremothers on the sack that she still had.

Brooke Gladstone Now, you initially set out to get answers, maybe even write the biographies of Rose and Ashley and Ruth, but you found unbridgeable gaps in the historical record. As a historian, what drove you to continue and how did your research goals change?

Tiya Miles In the beginning, Brooke, I felt confident that I could do it. I would be able to trace these women in the South Carolina records. It turned out that they are very difficult to trace with certainty, and that is the case with most enslaved people who didn't go on to do something that made them famous, such as Harriet Tubman or Frederick Douglass. These were women who lived their lives out in slavery. They were not freed until the Civil War. Never had the opportunity to learn how to read or write. They never escaped. And so it's much more difficult to identify them and to learn about the textured details of their lives.

Brooke Gladstone But in the paucity of information about Rose and Ashley, you still embarked on a history, but you wrote not a traditional history. It leans toward evocation rather than argumentation and is rather more meditation than monograph. And you name several scholars as inspirations. One is Saidiya Hartman, a professor at Columbia University who coined the term critical fabulation to fill the blanks. If you can't tell their particular history. You can tell the history of people in similar circumstances about which there may be information. You can tell the history of their time, which is documented and transparently make a case that this is possibly what they experienced or what they felt.

Tiya Miles Hartman introduces a method that really compels us to use our imaginations to fill in those gaps, because gaps are all over the historical record when it comes to enslaved people, black people, indigenous people, women. We could just throw our hands up and say, Oh, well, we can't find what we need, so we can't tell these stories. But that would be an additional injustice on top of the historical injustices.

Brooke Gladstone Let's talk about the contents of the sack. What Rose might have been thinking of when she packed it. For example, Rose included three handfuls of pecans. That type of nut was unusual for the mid 1800s. I learned from your book.

Tiya Miles Mm hmm. I thought that pecans were native to the Southeast. Because whenever I have gone down to the Southeast, I've seen pecans everywhere. So I first imagined her going out to a pecan grove and collecting the nuts from the ground. But it turned out pecans — they're native to places like Texas, Louisiana, even Mexico. And they would have been imported by elites as a delicacy in Charleston at the time when Rose was enslaved there, which meant she certainly would have known how prized these nuts were. She may even have known how nutritious they were. And in learning this information about the corn, I arrived at a conclusion which made sense when put together with other bits of information that Rose was probably a cook in the household of Robert Martin and his wife, Milbury Serena Martin.

Brooke Gladstone Of whom you paint a pretty persuasive portrait. These were people who were not old money, they were new money and who were eager to impress by offering exotic things like pecans.

Tiya Miles Mm hmm. Robert Martin started off as a grocer, worked his way up to been something like an accountant to old money Charles Stone in elites. And then he was able to acquire black people, which increased his status dramatically.

Brooke Gladstone How do you picture Rose getting her hands on three handfuls of pecans?

Tiya Miles I have thought about this. I have wondered how was she able to get so many? And it seems to me that the timing of the packing of the sack mattered. Robert Martin died in the winter of 1852, not long after Christmas, and I think it's very likely that Rose would have had pecans in the kitchen because they were used for holiday dishes. She may have had more pecans than usual at this time. She would have known when he died. And he may have suspected that this meant every single person in that household and other Martin Properties was now under the threat of being sold. And so she may have started to set aside some of those pecans. We don't know what she was thinking, Brooke. Maybe Rose was thinking that to pack the sack for herself and for Ashley, that they would run away together, that she had escape plans in mind. But the majority of enslaved people could not escape, especially those who were in the Deep South like folk. Carolina.

Brooke Gladstone Talk to me about the dress as you go through the clues in Ruth's embroidery. One of the words is tattered. It was a tattered dress. What did tattered signify?

Tiya Miles At the time that I was working on the book. Tattered signified to me an item that was worn, perhaps torn, frayed, used. But as I have been sharing information about Rose and Ashley and Ruth and the fact this reader told me that tattered may have been a way of saying tattered and that tattered or tatting is a way of making fancy lace. And so now I have these two interpretations which I think are equally arresting one of a worn and frayed dress and one of a very special dress with fancy lacing, either of which would have been very significant to Rose and her daughter.

Brooke Gladstone So there were the pecans, there was the dress. And then very fertile ground for your meditative approach. There was a braid of roses hair, because while the facts of their lives were sparse, the tradition of hair as a means of connection was long and rich. What did your research suggest about the inclusion of Rose's Braid?

Tiya Miles We know that enslaved people had very little opportunity to care for themselves, to take care of their needs for hygiene. And yet, in acts of resistance, they cared for their own selves and others. And one of the major ways they did this was by doing hair. They might braid their hair and cornrow their hair, twined their hair with a string or with a piece of vine. They would do the same for others in their community, for loved ones expressing love and dignity. Rose's hair would have been important in this way as a gift to Ashley, in that it could be a reminder of caring for oneself and of caring for others through the physical act of tending and adorning the body. And this braid that rose packed would also have been a very tactile way that Ashley could have part of her mother with her, even as they were separated for the rest of their lives. And I thought about this braid break. I also imagine the scene where Rose was freeing the spray from her own body to give to her daughter. And I thought about what a radical act that was, because in the system in which she was captured and the view of her enslavers, Rose's body belonged to the Martins. They were the ones who had the right to it by cutting her hair. Rose was asserting without words that no, her body belonged to her and she was choosing to share it with her daughter as an expression of love.

Brooke Gladstone You quote Laurel Thatcher Ulrich on what she calls the manic power of things. Things become the bearers of memory and information, especially when they're enhanced by stories that expand their capacity to carry meaning. Could you tell me about the quilt made by your great Aunt Margaret.

Tiya Miles That grown up here in the story of that quilt and given a chance to take a peek of that quilt which my grandmother kept stored and protected in her closet? And I always knew that the quilt was made by my grandmother, sister by my great aunt, and that this sister had been something of a hero in my grandmother's life. Because when my grandmother and her family were living in Mississippi in the early 20th century, they experienced terrible, traumatic events forced off their land by white men who had guns. And my great grandfather was forced to sign a piece of paper he couldn't read. He signed with an ax. This paper was some kind of property transfer, which meant that he was losing the land on which they lived. My grandmother told the story to me and my cousins growing up, and she always talked about how at the time when the family was being expelled from their home, her big sister Margaret, did something amazing. Margaret went out the back door of the farmhouse. She grabbed one of their cows. She took it over to a neighbor's home, which meant that even though the family lost almost everything during that expulsion, they still had that one cow. Due to the quick thinking and the bravery of my great Aunt Margaret. And my grandmother was a young child during this incident. And Margaret was only a teenager, as I. Tell you the story, Brooke. I am actually looking at the quilts that Margaret made because I inherited it. It hangs on my wall right now. And whenever I see this textile, I think of Margaret's bravery, of the possibility for resistance and resilience, even in the worst circumstances. That has been proven over and over again and the history of African-American women.

Brooke Gladstone In addition to being a historian, you're a writer of historical fiction, and you've said that for every historical work you've written, you're kind of drafting a couple of novels in the back of your mind. Can you give me an example?

Tiya Miles Yes. Well, I can't help it because, you know, as our whole conversation has shown, historical work is very important and I'm committed to it. But it is limited because we just can never fully reproduce the past. And no historical source can reveal in a whole and deep way the interior experiences of people who lived in the past. The place for that is fiction. It won't surprise you to hear that. Toni Morrison is one of my favorite authors, not just for her fiction, but also for her theory. And I write fiction because while I am thoroughly dedicated to reconstructing histories, I want to be able to say more, to move into that interior space, to open the doors that historical records always leave. LAMB sat in front of me.

Brooke Gladstone You mentioned Toni Morrison. You say that Beloved is a book in which love and horror are intimately connected, that she uses the notion of haunting, ghostly ness horror to tell a story about love. I immediately thought of the historical work I'd just been reading all that she carried horror and love intimately connected.

Tiya Miles The artifact of Ashley Sack is an artifact of trauma and sorrow and separation. And yet the sack itself, the way that it's been received across time, the way that its halls have been patched so lovingly, its story inscribed on the fabric with care and attention tells us this is not just a trauma story. This is not even mainly a trauma story. This is a story of love, of perseverance, of resilience, of survival. If not for those attributes, Ruth Middleton would not have existed to stitch this narrative onto the fabric. And when she does preserve that story for herself, for her daughter, and for all of us, now that we have the opportunity to review it and reflect on it. Ruth centers the word love. She highlights love. And she's telling us, I think, through that artistic decision, that this powerful emotion of affection and care and selflessness is key to her family's survival and perhaps to our own.

Brooke Gladstone Tiya, thank you so much.

Tiya Miles Thank you, Brooke.

Brooke Gladstone Dr. Tiya Miles is the author of All That She Carried the Journey of Ashley Sack, a Black Family Keepsake. Her novel, The Cherokee Rose, inspired by her research on a plantation comes out in paperback in June.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.