BROOKE: From WNYC in New York, this is On the Media. I’m Brooke Gladstone.

BOB:And I’m Bob Garfield. In Tuesday’s State of the Union Address, President Obama said it was time to “finish the job” of closing the prison at Guantanamo Bay, exactly six years since he ordered it “promptly” closed.

OBAMA: And I will not relent in my determination to shut it down. It is not who we are. It’s time to close Gitmo.

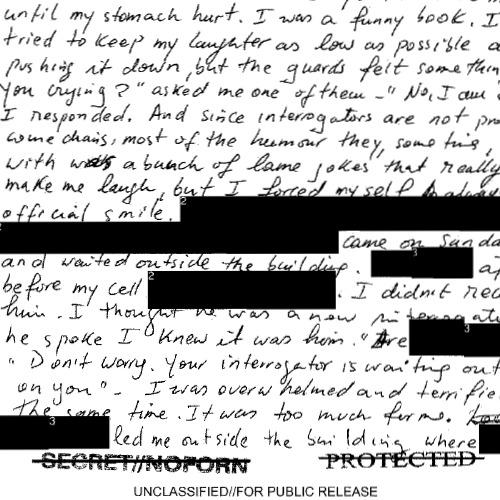

BOB: Of the almost 800 men once held there, 122 remain. One of them is Mohamedou Ould Slahi, whose book “Guantanamo Diary” was published the same day as the President’s address. Slahi finished his manuscript in 2006, but it took a six-year legal battle and the vigorous hands of censors before the government agreed to its release.

Larry Siems was the editor of Guantanamo Diary. He’s a writer and former director of the PEN American Center’s Freedom to Write programs. Larry, welcome to the show.

SIEMS: Thank you so much, Bob.

BOB: Let's begin why Mohamedou Slahi was even taken into custody. What did the government think he had been responsible for?

SIEMS: Well it's not even really very clear. The United States had interrogated Mohamedou even before 9/11. He was briefly in Montreal, he arrived there shortly after a man named Ahmed Ressam left Montreal. Ressam was picked up on the eve of the millennium trying to drive a car into the united states packed with explosives as part of what was called "The Millennium Bomb Plot." When he flew from Montreal to Dakar, Senegal, which is where his family was going to meet him and drive him back to Mauritania, he was detained by Senegalese security agents at the behest of the United States, questioned by the FBI about the Millennium Bomb Plot, and cleared.

BOB: Cleared because it turned out that he arrived in Montreal long after the perpetrators of the aborted plot had left town.

SIEMS: Exactly. So in November of 2001, Mohamedou gets another call from the Mauritanian security forces. They say the United States wants to ask more questions. He drives himself to the police station, he's put on a flight and sent to Amman, Jordan, where he's interrogated by the Jordanians for 8 months. The Jordanians again clear him of any involvement in the Millennium plot, but instead of sending him home at that point, the CIA turn him over to the military, and he's held briefly in Bagram and then delivered to Guantanamo in August of 2002.

BOB: And at every step along the way, tortured.

SIEMS: He is. The book describes what I came to recognize as kind of a modern day Odyssey. He covers 20,000 miles in an interrogation and detention route that includes detention facilities in Senegal, Mauritania, Amman, Jordan, Bagram, and ultimately Guantanamo.

BOB: Reviewers have variously compared Guantanamo Diary to the Salem Witch Trials and to the Trial, by Franz Kafka and the experience of Josef K. That definitely scans. Tell me about some of the things he heard while he was there from his interrogators.

SIEMS: They would come at him essentially saying, "We know what you've done, so tell us what you've done." And Mamadou of course would say, “Well, I've done nothing,” and they say, “No, come on.” And they would turn up the pressure even more. So it gives a picture of this kind of deadlock in the interrogation room that covered a period of months, even years.

BOB: Because he was told if he hadn't done something, he wouldn't be there. Which is a circular piece of logic as ever you'll encounter. Here's an excerpt read for the Guardian newspaper by Peter Serafinowicz:

Peter Serafinowicz (Excerpt): You joined the wrong team, boy. You fought for a lost cause, he said, alongside a bunch of trash talk degrading my family, my religion, and myself. Not to mention all kinds of threats against my family to pay for my crimes, which goes against any common sense. I knew that he had no power, but I knew that he was speaking on behalf of the most powerful country in the world, and obviously enjoyed the full support of his government. However, I would rather save you, dear reader, from quoting his garbage.

SIEMS: One of the incredible things is how empathetic in many ways Mohamedou is with his interrogators and the position that they've been put in. And he thinks and talks very specifically about the dilemma of the interrogators. They don't know - they're just told that these are very, very bad guys, these are the worst of the worst, now go get information out of them. So they too are kind of caught in this very Kafka-esque drama. And for the first time I think one of the most vivid things about the book is it really presents the human toll of this experience on our servicemen and women and intelligence agents, something that we've never seen before in any of the documents or literature that's come out of Guantanamo.

BOB: It amazes me that Slahi was even permitted to write the book, to keep the pages. How were they not confiscated by his captors for use in their own intelligence-gathering?

SIEMS: Well, I don't doubt that they were. in March of 2005 when they finally granted lawyers access to the prisoners in Guantanamo, he greeted them with a bunch of papers in which he sort of began to tell the story, and he started telling it for them. Very quickly that changed to the book that was being told for us, for the American people. At this time in 2005, there's a conscious effort to rehabilitate him. I mean we took him to the absolute brink at a moment that incidentally is corroborated by the documentary record, is a moment where after, you know, extreme sleep deprivation and brutality, he begins to hallucinate that he's hearing voices and he hears the voices of his family, and sort of heavenly Qur'anic readings.

So that's where he was in the fall of 2004 and then they start to bring in a fresh team of guards, he got pen and paper during that time and i think it was part of a clear effort to help restore him physically and emotionally. What's amazing is that he manages to compose something that's, I mean, composed in every sense of the word, from a writerly sense to an emotional sense to a sense of perspective and real generosity and even forgiveness.

BOB: Until now, for the most part, Guantanamo detainees have been exotic people with unpronounceable names in orange jumpsuits accused in one way or another of participation in terrorism--not the most sympathetic cohort, right? And now there's a human face and a particularly eloquent one. What has been the reaction so far?

SIEMS: Well, it's been astonishing and a really hopeful thing to watch. I think what people are responding to is, when you open this book you stop dead in your tracks because you realize that you're hearing a voice that's come out of what has been an incredible void. The thing that you describe of the sense of the Otherness of the prisoners, what's incredible is to watch the interrogators and the guards, many of whom come to that place with those feelings, and we all have misconceptions and those misconceptions have been fueled by the secrecy and when that secrecy is broken and you actually hear a human voice and you see how harrowingly intimate the human exchanges are that take place there, you have to stop and listen.

BOB: In a response to a habeas corpus filing, he was actually ordered released 5 years ago by a federal judge. But the government appealed the decision and he's been in Guantanamo limbo ever since. So what is he still doing there?

SIEMS: Let's start with the fact that we shouldn't even be asking that question, right? He's been in there for 12 years, he's been in US detention for 13. We should be able to explain to ourselves why he's there, but we can't. The story of Guantanamo writ large is a story of secrecy, it was created to be a secret space so that mistreatment and torture could happen. Even when the torture stops, secrecy began to serve the purpose of covering up those misdeeds and those crimes, and delaying accountability for those crimes. I think to some extent his story and the story of many other--we know now--quite clearly innocent men who are still in Guantanamo, has been a story appallingly of simply prolonging the inevitable and along the way perpetuating terrible mistakes. And what this book does for the first time is it reframes the whole discussion about Guantanamo on a human level, and it reminds us that deferring dealing with terrible mistakes that we've made means endlessly prolonging the suffering of their families. And it means - and I think the book makes very clear - prolonging the burden that we put on our own servicemen and women who have been put in this position, and it's time that we assume that ourselves.

BOB: Larry, thank you very much.

SIEMS: Bob, thank you so much, I really appreciate it.

BOB: Larry Siems is the editor of Guantanamo Diary.