The Forecasts Didn't Help Us

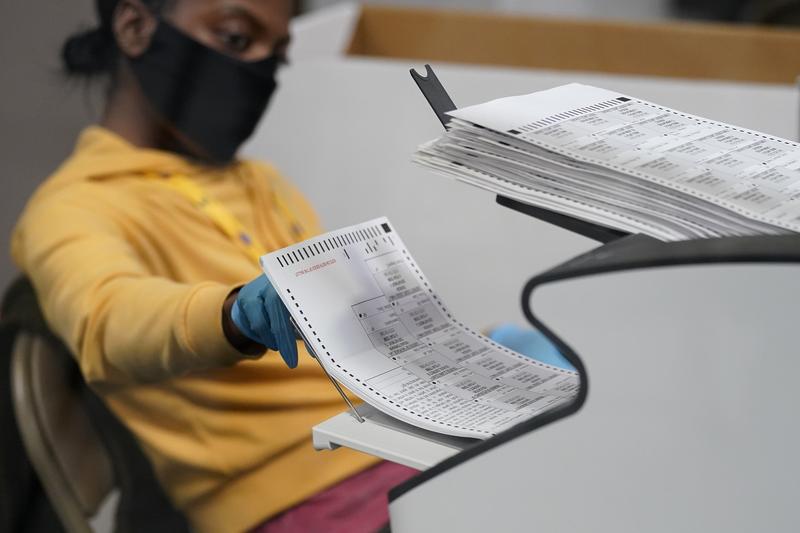

( John Locher / AP Photo )

BROOKE GLADSTONE This is On the Media, I'm Brooke Gladstone.

BOB GARFIELD And I'm Bob Garfield. Mere hours into election night, the forecasters fired up their Twitter feeds and graced our TV screens ready for model combat.

[CLIP]

NATE SILVER So coming in, we had Joe Biden with an eighty nine percent chance of winning. Trump with 10 percent, 1 percent chance of a tie. [END CLIP]

[CLIP]

HARRY ENTEN You know, even if you don't believe the polls and you'd say it takes some sort of discount, you still should have Joe Biden. [END CLIP]

[CLIP]

SNL BIDEN Nate Silver, you will know the score, even though.

SNL NATE SILVER I was wrong before. [END CLIP]

BOB GARFIELD That clip wasn't ABC. That's an impression of Nate Silver on Saturday Night Live just days before the election.

[CLIP]

SNL NATE SILVER So, look, guys, our current model shows that Trump has less than a one and six chance of winning. About the same odds as the number one coming up, when you roll a die. So for example, one. I guess that shows you that it's technically possible, however unlikely. But roll it again and you'll see that it's a hard one. [END CLIP]

BOB GARFIELD Forecasters predicted a democratic romp, a blue wave, a tsunami.

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORTS Democrats expected. Nancy Pelosi even said on our air she thought she would win five, 15, 20 seats. They're going to lose seats. It looks like Susan Collins, Republican of Maine, survives a very, very rigorous challenge from Sara Gideon the House speaker in Maine. But look at this as a big win. Talking to her campaign, they're incredibly pleased. No one thought. [END CLIP]

[CLIP]

SUSAN COLLINS I am the first person since Maine directly elected its senators to win a fifth term. [END CLIP]

BOB GARFIELD As of Friday afternoon, Trump had outperformed the 538 polling average in every swing state. This isn't a dump on 538 because, you know, the polls on which it based its calculations were flawed. They vastly underestimated the Republican vote. But according to Zeynep Tufekci, associate professor at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, forecasting models and the inadequate polls that feed them aren't just unhelpful or inaccurate. They're harmful.

ZEYNAP TUFEKCI When we go to these models, we're looking for a prediction. And when you look at it and it says nine chances out of 100, Biden would win, it's kind of hard not to be overwhelmed by what looks like a prediction for a landslide.

BOB GARFIELD We hear 87 percent probability, but what we register is 87 percent of the votes cast, which sounds like a landslide. Is there any evidence statistically that people simply fundamentally misunderstand the percentage?

ZEYNAP TUFEKCI Now, there's academic studies that show that people see a big number, and while they may or may not confuse it with vote share, the bigger point is that they get a sense of certainty because the numbers are so big. And given how many times we see polls with vote share in our lives, it's really hard to cognitively make that switch. And even if you're able to cognitively make that switch, it's really hard because just the way it looks and feels and that's what we're refreshing for. A lot of times I see people just refreshing these things almost as a way to soothe their anxiety because they're worried about what the outcome is going to be. And I just want to say that comfort you seek isn't there because there's so much uncertainty, but that's not communicated.

BOB GARFIELD We do stay in touch with Nate Silver and he mentions a structural problem in the process of modeling itself and namely that there wasn't much data to build the models upon.

[CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE How many elections are we really talking about to base these predictions on?

NATE SILVER Well, since 1972, which is when you had the McGovern reforms and you start to have people actually vote in primaries before it sort of literally was smoke filled rooms. It's depending on how you count somewhere on the order of 10, 12, 15. To say something hasn't happened in 12 tries is much different than when we also make sports predictions. And we can say, well, this hasn't happened in a thousand games, then you're more existentially certain that something is really unlikely. Then you can be in the nomination process or for that matter, the general election to where there have been, I think, 16 or 17 now elections since World War Two in the polling era. That's not a huge sample size either. [END CLIP]

BOB GARFIELD Precious little baseline data and ever-changing conditions such as just, for example, Facebook or as you mentioned in your New York Times piece, the the sudden intervention in 2016 of James Comey talking about Hillary's emails. Things that tend to stymie any attempts to extrapolate on a thin database to begin with. How untrivial is this structural problem, do you think?

ZEYNAP TUFEKCI It is a structural deathblow to the idea that we can reliably model presidential elections? You're basing their whole model on very few events, right. So you can only see what happens to your model, how it performs once every four years. And it's not like you really evaluating the model because every four years there's major differences. We didn't even have Twitter just a couple elections ago. Facebook played a major role in 2016. So there's all these things that are hard to model, plus the inputs into these models are polls. But right now, polling response rates are like six percent, three percent like people aren't picking up their phone. Plus, there's a lot of evidence now that some people see pollsters as a cultural enemy and that those people tend to be supporters of President Trump. So you're missing a substantial segment of the populace, but you don't really know how much of them there are. It's an unknown, unknown.

BOB GARFIELD Garbage in, garbage out.

ZEYNAP TUFEKCI Now, compare that with whether the weather modelers, they get to check their model every single day. So without reliable polls, we don't even know if the models are good. And I'm not even sure what the value added from the models would be if the polls were indeed reliable. We're looking for a scientific prediction when it's not really possible. What is the point of these forecasts if they're not the forecast? That's how people interpret them. We see them as predictions. And worse, there's a lot of evidence and reporting that shows that the forecast itself affects the outcome. That's where they differ from weather forecasts, right. If I don't take an umbrella, the rain is not going to happen just to spite me. Whereas if I think something's more likely to happen and act in a particular way, I may actually be changing the odds it's going to happen.

BOB GARFIELD What you're saying seems to be describing the Heisenberg effect, where the act of measurement actually affects the experiment itself. You believe that voters are actually behaving influenced in part by what they're reading in the polls and particularly the models. Especially, for example, if you think that your candidate already has 87 percent of the vote locked up, why bother going to the polls at all?

ZEYNAP TUFEKCI Of course, it affects the way people behave in the 2016 election. We have FBI Director James Comey on the record saying that he thought Hillary Clinton was basically a shoo in for winning, I'm paraphrasing, and that affected his decision to release that letter, which dramatically impacted the race. There's a lot of reporting that says the social media companies themselves thought Hillary Clinton was going to win. You see a pattern here? And decided not to take some actions on the widespread misinformation on their platforms waiting for the election to be over. There was a famous tweet by Edward Snowden attached to a New York Times forecast showing 93 percent chance of Hillary Clinton winning the presidency, saying there's never been a safer time to vote for a third party, and there's no doubt there were people who thought the same thing and might have cast what they thought would be a protest vote, but ended up helping Mr. Trump. And there's no reason to think this is not the case this election, too, because if you want to, for example, prevent a Democratic trifecta and if you think President Biden's absolutely certain to win, you might vote for a Republican senator thinking that will help balance the Democratic president. You might be thinking, for example, voting in Maine, Susan Collins, she is winning, but the polls before we're showing her losing. So it might be the polls were wrong or it might be that people saw the polls and people saw the predictions for the Biden presidency and decided, well, we can return her as a minority senator. Instead, she's likely going to be a senator in a majority Republican Senate.

BOB GARFIELD Based on your Times op ed and a blog post on the same subject, I would say that you have something like the zeal of the unconverted. Back in 2012, you were quite an apostle of modeling. You wrote a piece in Wired defending Nate Silver and his work from critics, mostly on the Republican side, but not entirely. So why the change of heart?

ZEYNAP TUFEKCI I really was hopeful when the models first came on the scene because at the time there was a lot of horserace coverage. You know, who's going to win, who's not going to win. That was driven by pundits, and in a way, they were almost exaggerating the uncertainty, I felt to create tension and narrative. And I thought, you know what, polls and models are better than that. You know, whatever their shortcomings, and that will hopefully, I thought, give us a opening to say, all right, this is what the models say. And now let's talk about the policy, let's talk about the substance. Let's talk about what's at stake at the election. What I didn't foresee is that the models have become completely incorporated into the horserace coverage. So instead of reading the tea leaves by counting, you know, signs on lawns and things like that, the punditry is very happy to say, oh, the model's gone from 89 percent to 91 percent. Again, not acknowledging the limits of the method.

BOB GARFIELD So far from 538 and other models being alternatives to horserace coverage. You know, they're freakin Hialeah. That's a big racetrack saying up. I'm not sure if you're aware of that. Are you aware of that?

ZEYNAP TUFEKCI I did not know I was going to ask you. That's what it has become though. But the thing that we can do is vote, organize, donate. And that's the only thing that actually affects who's going to win in a healthy manner compared to this kind of constant refreshing that overwhelms. And, you know, after 2016, we should have learned that these things aren't as reliable as we feel they may be. But we went into 2020 almost not remembering what happened and it happened again. And I just feel like maybe we should remember next time and not be so focused on these weak methods.

BOB GARFIELD Now, Zeynap, um, you and I have something in common. We both live on Earth, and as such, we both have the experience of knowing that when tools are available, they are irresistible to those who depend on the latest thing to do their jobs, which is why police used tanks to deal with the burglary and why statistical models have become the center point of our election coverage. In other words, do you expect things to get worse before they get better?

ZEYNAP TUFEKCI I'm a social scientist myself and I live on planet Earth, as you say, and I get the attraction of wanting to predict, but it's just not possible to do it well with our given polling techniques, modeling possibilities and the data we have. What we should just do is say, OK, you know, polls might be useful for campaigns and they'll keep polling. Models have their place, you know. They're good for, for example, trying to figure out if there's fraud. You can look at correlates and things like that. So it's not that they're completely without their use, but we should just put them in their place. And that's not the front page, and that's not top of our minds.

BOB GARFIELD Zeynap, thank you very much.

ZEYNAP TUFEKCI Thank you for inviting me.

BOB GARFIELD Zeynep Tufekci is a contributing opinion writer at The New York Times and author of the newsletter Insight.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Coming up, conservatism isn'tm and never has been, a fan of one man, one vote. I mean - never.

BOB GARFIELD This is On the Media.

Copyright © 2020 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.